The Art of Listening Is Political

In addition to performing internationally, composer and vocalist Kristin Norderval divides her time between Oslo and New York, a contrast that perhaps mirrors her own intrepid lifestyle as an artist. She laughs that there are more people riding the daily subway throughout the five boroughs than there are people within the entire country of Norway.

Earlier this month, Norderval sat down to share her thoughts shortly before playing with Guillermo Gregorio at the Culture Project’s Prologue to Progress series in New York. Even a cursory glance at her artistic output as a performer, composer, and collaborator, one sees a body of work which is diverse and far-reaching, a breadth of imagination which seems to know no bounds. Norderval has performed as a soprano soloist with prestigious companies such as the Philip Glass Ensemble and the San Francisco Symphony. In addition, chamber operas by Anne LeBaron, Francis White, and others have been composed specifically for her and her voice. The totality of her original compositions frequently cross over multiple styles and genres. Rooted not only in the operatic traditions of her background, Norderval’s artistic language also incorporates electronic music, cross-disciplinary performance, and the nuances of the human voice.

Listening can be interpreted as a kind of activism. Listening itself becomes a fully-embodied pursuit, challenging the traditional hierarchies embedded not only within the arts (particularly classical idioms such as opera and music), but fostering a positive environment of inquiry.

Perhaps this holistic approach to sound and performance stems from her global upbringing. “I grew up in four different countries and a dozen different cities by the time I got to college,” the Norwegian American says with a radiant smile. “That gave me a lot of perspective about different ways of living and working.”

And while she admits that the sheer volume, competition, and excitement of artistic institutions in New York is incredible, Norderval also passionately believes that America could learn a lot from the European model of arts funding. “Public funding is almost nil in the States, so everyone works at other paying jobs,” she explains, resulting in artwork that is either commercial or funded by privatized donations. Which means that, according to Norderval, “art for the rich and by the rich. Or, by those who are good at begging from the rich.” Norway and other European countries offers an alternate model, where:

The arts are seen as a public resource that should be supported. This means both that there is funding for good education in the arts, and that artists from all walks of life have a chance to actually earn a living with their work. That’s something I believe in really strongly, and something we have to make sure to protect! To give you an idea of the difference between these two models of arts funding, think about this: the city of Berlin—between local funding and national funds ear-marked for their local arts institutions—has an arts budget of about a billion euros (approximately 1.2 billion dollars). Compare that to the US National Endowment for the Arts, which only has a budget now of about 150 million dollars (about 127 million euros). For the entire country!

Norderval shakes her head in bewilderment. “I always advise people not to copy the US model.”

While Norderval was an undergraduate composition student at the University of Washington, she first began listening to the recordings of and reading the writings of Pauline Oliveros. The inspiration touched her not just artistically, but also on a personal level.

Hearing her perform was amazing. Then reading her text scores and seeing her graphic notations was eye-opening and inspiring, as was the fact that she was brave enough to out herself in the introduction to her collection of Sonic Meditations (1971). This was a time when there was a lot of prejudice against female composers, and a lot of homophobia, so not that many composers were open if they were gay or lesbian.

After completing her classical training at the doctoral level from the Manhattan School of Music, Norderval studied with Oliveros at The Deep Listening Institute (now the Center for Deep Listening at Renssalaer Polytechnic Institute), a three year certificate program. Subsequent concertizing and recording opportunities with Oliveros gave Norderval both the tools as well as the confidence to improvise within her own art. These years of study and collaboration clarified what her mentor’s approach to improvisation as “real-time composition” meant, and could mean for years to come.

Oliveros’ instructions and suggestions on listening can be interpreted as a kind of activism. Listening itself becomes a fully-embodied pursuit, challenging the traditional hierarchies embedded not only within the arts (particularly classical idioms such as opera and music), but fostering a positive environment of inquiry. Oliveros’ perspective invites us to question not just how music and sound are created, interpreted, notated, and produced, but also interrogates the systems which frame how we experience these expressions.

‘For every piece that I create, I try to find the core sonic elements that belong to that artistic, imaginary world.’

For decades, Norderval’s original projects have courageously embraced multifaceted political content, while simultaneously deploying a multilayered approach to sound that nods to both her classical lineage as well as her contemporary, electronic, environmental aesthetic. Her interdisciplinary, collaborative project Welcome to Paradise: A Requiem (2008) staged at Oslo’s Kanonhallen questioned why many countries in Europe and beyond cooperated with the American program of secret prisons, groupthink, and Guantanamo Bay. “At the end of that project, I knew a lot more about torture,” Norderval admits with a sigh. “I wanted to work on something that would give a personal portrayal of what it takes to endure such extreme violence, but I also wanted something that could give hope, especially in the idea of accountability.”

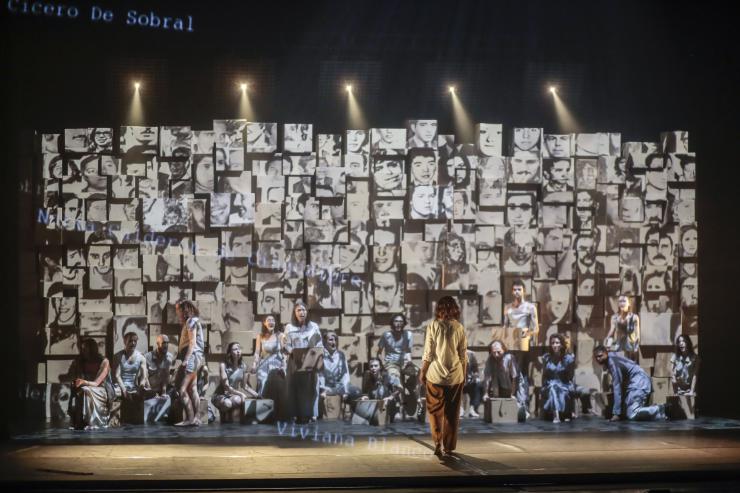

Shortly thereafter, Norderval heard Patricia Isasa speak about successfully winning her 2009 court case convicting six perpetrators responsible for her kidnapping and torture in Argentina. She immediately knew she wanted to find a way to work with Isasa on her story. “Patricia is an amazingly strong person,” Norderval affirms. “I was honored that she was willing to meet me, to be interviewed, and to have her story dealt with in this form.” Their taped conversations formed the basis of the libretto, written by Obie Award-winning playwright Naomi Wallace. The resulting two-act opera, The Trials of Patricia Isasa, premiered in 2016 at the Monument National Theatre (Montréal) in a Chants Libres production.

“For every piece that I create, I try to find the core sonic elements that belong to that artistic, imaginary world, that can express that world in the fullest and most convincing way,” Norderval shares. “That is always the same. But sometimes that is a solitary process and sometimes it is in collaboration with others.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here