History of Revivals

How did theatre become the way it is today? This blog series will look at aspects of our present-day theatre that we take for granted and explore where they came from. It will also feature interviews with theatre archivists about their work and how it relates to new theatrical productions.

The film industry is doomed, or so we’re told. Studios have come to rely so heavily on rebooting and remaking blockbuster franchises that they’ve come close to eliminating movies that are modest in terms of budget and spectacle, but far more original and artistically ambitious. Television has become a refuge for many filmmakers looking to create this kind of work, but even it seems susceptible to the lure of simply rehashing old hits.

This might seem like a moment for self-congratulation in the theatre world. After all, theatre’s ephemeral nature means that it’s always new, never quite an exact rehash of the same old thing. However, there’s a striking paradox at the heart of the theatrical experience: throughout its history, the theatre has often relied on old material. Indeed, we often view the revival of a classic work as a prestigious move, one that confirms our cultural bona fides and usually guarantees us an audience. Furthermore, a revival doesn’t simply entail rehashing old plots and characters, but rather performing the exact same script that previous generations have performed, sometimes for centuries. We throw up our hands in exasperation at the news that Hollywood is rebooting the Spider-Man franchise for the umpteenth time, but it’s virtually inconceivable that a major studio would simply reuse the script from a previous film.

The prevalence of revivals and the tyranny of the classical canon often warrant handwringing among those who make and write about theatre, but it rarely leads anyone to conclude that theatre is creatively bankrupt or doomed to inevitable collapse. What is it about the theatrical revival that’s different? What makes the re-presentation of familiar material compelling on the stage in a way that it’s not on the screen?

Revivals are almost as old as theatre itself. The citizens of Athens voted in the mid-fifth century BCE to supply chorus members to anyone who wanted to revive the work of Aeschylus as a way of honoring the playwright’s memory. Most of the ancient Greek plays that we’re familiar with were revived in later centuries through the rise of the Romans. In fact, Plautus and Terence claimed to be doing little more than translating Greek plays into Latin.

It’s sort of beside the point to call the productions staged by medieval actors “revivals,” since many of them served a ritual function, and were performed annually on religious holidays. The term becomes more appropriate when we consider the commercial theatres around London in the early seventeenth century. Places like the Red Bull Theatre became known for their revivals of older work by playwrights like Christopher Marlowe, who had died more than a decade before the Red Bull became a permanent theatre.

In many cases, it wasn’t only the script that theatre companies revived. For almost a century after the reopening of the theatres in England after 1660, several major London stars actually prided themselves on imitating older actors, thereby continuing a tradition of playing roles the way they’d been done in Shakespeare’s time. This was more common than we might think: actors in many traditional Chinese and Japanese theatrical traditions also worked from a classical repertory of plays, and successive generations of actors played their roles in carefully prescribed ways passed down from their predecessors.

The American theatre has a complicated relationship with revivals. After all, this is supposed to be the country of the new, but reviving old plays raises some awkward questions about our identity. Danielle Rosvally, who’s been studying the origins of America’s Shakespeare mania, shared with me that Shakespearean revivals weren’t initially major draws for American audiences. William Dunlap, one of the fathers of American theatre, went broke in the early nineteenth century trying to sell Shakespeare to New York audiences. It looked like the young republic might break with English theatrical traditions after all; however, Stephen Price, a ruthless businessman who sensed that there’d be money in bringing over English stars, eventually replaced Dunlap. Rosvally says those stars began to sell Americans Shakespearean revivals. Roles such as Macbeth and Hamlet became staples in the repertoires of American stars such as Edwin Forrest and Edwin Booth.

We’re always grappling with our history, always tweaking which aspects of our theatrical traditions we choose to emphasize.

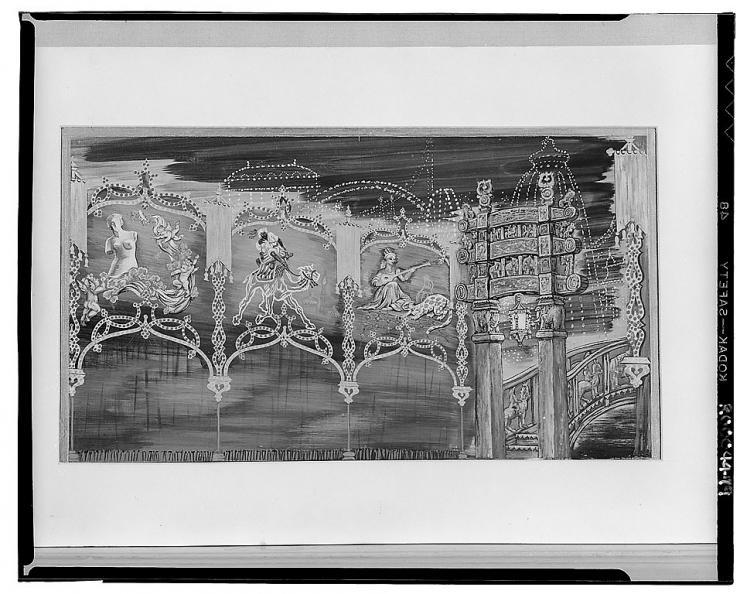

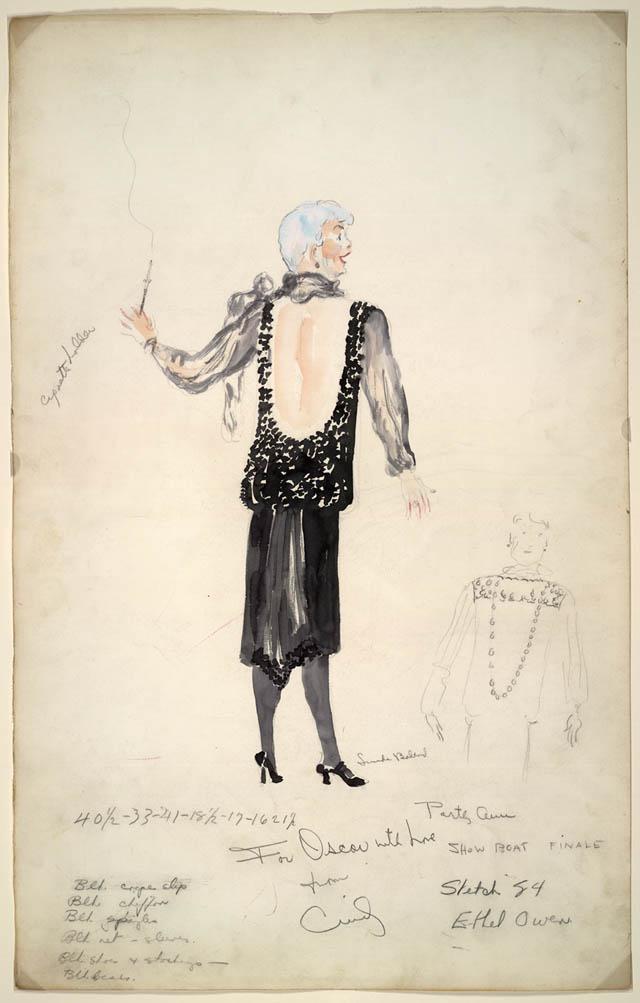

The twentieth century saw the rise of another revival mainstay: the American musical. You probably know Show Boat as the first modern musical in the sense of having a coherent plot, and songs that were integral to that plot. However, those attributes meant that it was possible to revive and reinterpret Show Boat in a way that wouldn’t make much sense with the Ziegfeld Follies of 1926.

I think it’s more than clear from this not-so-brief history that revivals have been integral to theatre almost from its inception. In my mind, one of the most striking conclusions that we can draw from concerns the role that tradition plays in the theatre. Although the work that’s being revived is secular in nature, the motives for reviving it are primarily commercial. Howard Sherman opines in his 2012 piece that, “perhaps … classics should be celebrated, because they can often show the current generation what craft and talent in the form has looked like in the past, in order to inform the future.” In a similar vein, a recent New York Times story, that’s mostly positive about the success of the British theatre in fostering new work, ends by quoting Canadian theatre scholar Holger Syme’s concerns “that a theatre that doesn’t wrestle with its own past openly, repeatedly, continually, also lacks a vital element.” It’s difficult to imagine anyone connected with the film industry arguing that every generation should have its chance to reinterpret The Wizard of Oz or The Godfather.

This last point leads me to a final observation, which is that revivals point to a unique quality of the theatre: there is a sense that works are never quite finished. Tampering with The Third Man seems like sacrilege, but to modify the setting, casting, or even text of Richard III seems the most natural thing in the world. There’s a sense of self-reflection inherent in theatre that isn’t evident in movies or TV. We’re always grappling with our history, always tweaking which aspects of our theatrical traditions we choose to emphasize. In that way, we can continue reviving classic works because we can remake them. By doing so, we get them to speak to our unique circumstances in new and exciting ways. The fact that we keep returning and reexamining older works is an indicator of theatre’s ability to adapt and change in a manner that other forms hope to emulate.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

The only time I can recall a film using the same script twice was that off PSYCO remake, a few years back. I think it even recreated each shot!

Oh God, I'd forgotten about that! There's almost something experimental about reproducing a movie, what an odd idea...

OR...It is a reflection of our laziness in creation?

It is easier to begin with the structure of the past than to create anew.

I think there's a sort of creativity in having to reimagine something within set parameters, though! Think of how Shakespeare has been reinterpreted throughout the last few centuries.