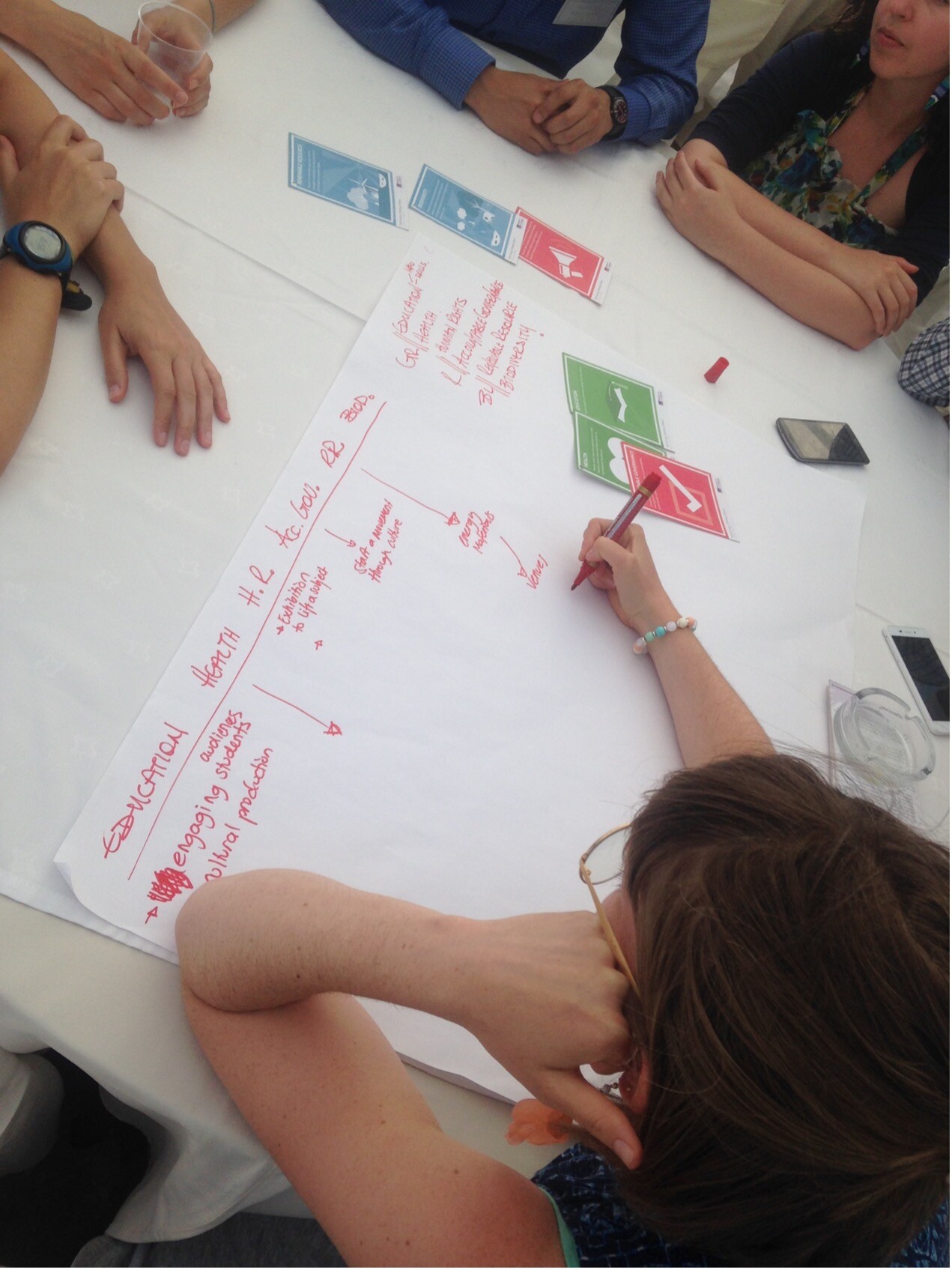

I am a founding member and general secretary of the European theatre network mitos21, which set up a green managers’ group in 2014. The program functions as a peer learning initiative, given that one of the network’s members, the National Theatre in London, was already a recognized international leader of sustainable practice when the group began. It soon became clear from the group’s convenings and its varying levels of environmental literacy that member theatres and their teams needed a more systematic understanding of environmental issues and the methodologies and processes of embedding sustainability in practice. In 2016, mitos21 launched the Sustainable Cultural Management international course, which was co-designed with the cultural and environmental charity Julie’s Bicycle. In June 2016, a weeklong pilot edition was taught by leading international experts and peers with hands-on experience. It covered all areas of sustainable management, including theatre buildings, daily operations, stage production, and artistic programming. It also included an introduction to environmental issues and the climate crisis, and a day dedicated to best practice examples from the cultural field.

Building on Global Movements

In the performing arts sector, the desire to become actively engaged in the ecological transition gained urgency following the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015, the Fridays for Future climate movement in 2018, and the European Union Green Deal in 2020, among other relevant landmark events.

Setting an example of environmental commitment, multi-arts venue HOME in Manchester, United Kingdom, has prioritized the empowerment of their team by providing the skills and knowledge to communicate climate awareness and drive change. HOME is the first arts and cultural venue in the world to have 100 percent of its staff trained in carbon literacy as certified by the Carbon Literacy Project; in-house staff trainers deliver regular workshops, ensuring that all new starters are trained within six months of joining the HOME team. Training is proven to have a very positive impact, “amplifying HOME’s mission [of] sharing knowledge, influencing others, and inspiring action in our commitment to collective responsibility, accountability, and action.”

There is a significant surge in the demand for environmental training and capacity building among theatre professionals and an increasing number of performing arts institutions.

As more and more arts practitioners have become environmentally aware, several other initiatives have been developed in response to the need for capacity building and professional empowerment. Julie’s Bicycle created the international Creative Climate Leadership course; the mitos21 Sustainable Cultural Management course continues to evolve, with the most recent version co-designed with the European Theatre Convention in 2022 and jointly delivered to more than seventy member theatres across Europe; KiFutures, an international coaching and training network for sustainability in the arts, was launched by KiCulture in 2021; and the Broadway Green Alliance has taken the Green Captains program to the next level with over eight hundred Green Captains across the country on Broadway, off-Broadway, and in regional theatres, as well as an active College Green Captain program that provides free educational and engagement opportunities to student artists and climate activists at over seventy colleges and universities.

These initiatives, which are mostly international in character and ambition, contribute to the creation of an ever-growing global community of like-minded culture professionals and expedite the sharing of existing knowledge and expertise across borders. They also demonstrate that there is a significant surge in the demand for environmental training and capacity building among theatre professionals and an increasing number of performing arts institutions.

In view of the climate emergency, though, is this enough to instigate the fast and broad sectoral change required? In my recent book Sustainable Theatre: Theory, Context, Practice, I argue for more “learning” versus “unlearning” to address what I see as a paradox: while members of the existing workforce upskill themselves to meet climate and environmental challenges, future theatre professionals are still trained by and into a system which, in certain aspects, is becoming obsolete.

In these examples, sustainable practice is meant to cultivate sustainable thinking.

Re-Skilling and Upskilling—Ad Infinitum?

In his article “The Ethical Turn in Sustainable Technical Theatre Production Pedagogy,” theatre artist and academic teacher Ian Garrett emphasizes that the formative years—in universities, colleges, academies, and drama schools—establish the values that guide students’ future professional practice. He describes the dominant pedagogical model as a combination of theatre and performance studies with “an apprentice-style transfer of established practices”; once out in the professional field, students tend to reproduce conventional methodologies, “while opportunities to explore novel methods of theatre making diminish.”

Since 2012, Garrett has been professor of Ecological Design for Performance at York University in Toronto, Canada, one of the very few educational institutions in the world to have a graduate program dedicated to sustainable production. There has been only a handful of sustainability initiatives in an academic environment so far, mostly developed in the unique universe of academic theatre in the United States. An early example is recorded in Justin Miller’s “The Labor of Greening Love’s Labour’s Lost,” an account of his experience as a post-graduate student at Michigan State University (MSU) working on a project undertaken by the Department of Theatre in collaboration with MSU’s Office of Sustainability. The project aimed to develop greener production practices to help teach the next generation of theatre designers and technical managers how to incorporate ecological concerns into their work.

Another such project, the Sustainability Scholars Program led by Paul Brunner and Olivia Ranseen at Indiana University in 2015, paired students with faculty mentors to conduct research on a given environmental topic. Their research outcomes served as groundwork that allowed the theatre department to investigate “how to make an academic theatre production more sustainable from beginning to end and from bottom to top” and implement knowledge gained through this educational exercise.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

thanks for highlighting some international initiatives here; may it help momentum of scaling this to grow!