Intermittence

A Circuit of Theatrical Desires

On April 18, 2016, the Théâtre de la Ville, one of the biggest theatres in Paris, changed its role for a night. That Monday from 7 p.m. until around midnight, the theatre served as a meeting point for more than a thousand professionals in the performing arts. The aim was to discuss how they were going to face the government’s proposal to change the specific social security conditions that performance artists and technicians benefit from in France. I was surprised to receive a ticket saying “General Assembly of Intermittents—Free Seating,” and discover ushers indicating where I could sit. There was a stage set with an elongated table, and three women ready to talk. What kind of performance was I attending? Had the theatre really changed its role, or rather actualized it? That same Monday, and later in the week, general assemblies of this kind were held in Montpellier, Cannes, Lyon, Nice, and Marseille. In the weeks to come, the ensemble of artistic professionals known as intermittents managed to occupy a dozen public theatres across France in an eloquent political gesture, positing a new understanding of the public space. This didn’t look much like contemporary French political theatre—but given where it was staged, how could it be called anything else?

[In April 2016] the ensemble of artistic professionals known as intermittents managed to occupy a dozen public theatres across France in an eloquent political gesture, positing a new understanding of the public space.

Who Are the Intermittents?

Today, most professionals in the industry would not be able to explain this extremely complex bureaucratic system, often hidden with French legal terminology in an obscure dialect for both native and foreign populations. The conditions are also slightly different between so-called “artists” and “technicians,” but here are the basics: a condensed, simplified version of the current legal status of the intermittents du spectacle.

Intermittence is a special taxpaying category in France that dates back to 1936, and accounts for artistic professionals who work through short-term contracts. In other countries such as Italy, the UK, or the USA, dancers, directors, and designers are counted as liberal professions, as opposed to artisanal or commercial: a category that establishes them as independent contractors who either take care of their own social security, or are in charge of redacting bills for their employers, according to the service they have offered. The intermittence appeared in a time when the cinematic industry was starting to flourish and producers found it difficult to convince technicians to abandon their full-time, socially secured contracts for a mere five or six-month engagement. This new form of social security, labeled “intermittence” for its temporal characteristics, provided an advantageous incentive for them to ride the rollercoaster of cinematic production. In the 1960s, when work in the theatres became more and more intermittent and delocalized, the status extended to all those working in the theatres, including directors, actors, and musicians.

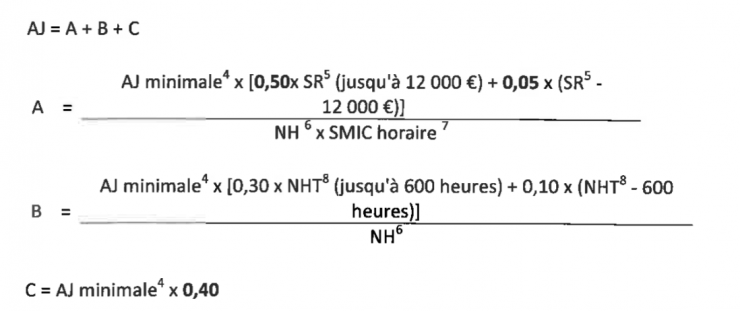

The status applies to professionals working in cinema, audiovisual, and performance arts who can justify a total of 507 hours of labor throughout the 319 days preceding the end of their most recent contract—if they fulfill this basic condition, they acquire the title of intermittents, and can receive unemployment benefits. These are necessarily paid hours, which include taxes that go towards this state-led unemployment insurance. It covers for maternity leave and work-related accidents, but also requires that professionals cannot have refused previous professional activity for artistic reasons. The salary received, as unemployment benefits, is the equivalent of five hours of work per day, for a maximum of 243 days. This salary is calculated according to the following formula, where “AJ” is the final yearly salary, which has to then be divided down to a day’s labor:

Understand anything? Exactly. Complaints of the state cheating the numbers when assigning unemployment benefits are numerous—no matter who ends up being right, what is certain is that the discussion will last for a while. So when little changes are made, it is excruciatingly difficult for professionals working in these fields to understand the implications they bring along. The Coordination des Intermittents et Précaires (CIP), an association of intermittents, carries out multiple sessions of what they call “legal decryption” every time the government proposes a change to this law—which as it turns out, is quite often.

Intermittents are veterans of social mobilization. Employer federations in France have been trying to end this status for the past two decades, as they consider it to be highly costly in terms of the amount of taxes they are obliged to pay. In 2003, as a response to one of these modifications, the intermittent workers of the Festival d’Avignon organized a strike that managed to cancel the official section of the festival in its entirety. Held in July, the Festival d’Avignon is arguably the most important cultural event in France and one of the most important theatre festivals in Europe, along with Edinburgh. In 2014, the MEDEF, the largest employer federation in France, demanded the elimination of the intermittence, which resulted in an agreement with the government to reduce the allowances given to unemployed intermittents. Again, one of the main targets was Avignon, where the opening ceremony and shows were cancelled. Despite their continuous resistance efforts, the benefits of the legal status of intermittents are slowly being diminished.

Come 2016, the story repeats itself once again: the MEDEF demands for the status of intermittence to economize 185 million euros, in the context of an effort to reduce national debt. The government puts forth a series of proposals, ready to modify the law: augmenting the number of required labor hours to enter the status, reducing the days during which those hours should be accomplished, or simply shifting the way of counting so that particularly productive periods for some performers, such as summer season, would be more difficult to include. This year, Avignon has not suffered much: a couple dress rehearsals were interrupted by intermittents, and there were strikes before the beginning of the festival. The actions happened much earlier—in the beginning of the spring and in line with Nuit debout, which roughly means “a night standing,” a latecomer to the global Occupy protests.

When the general assembly at the Théâtre de la Ville on April 18 decided to go on a general strike and attempt to occupy public theatre spaces, Nuit debout was at its height. Day after day, the Place de la République in Paris, as well as many other squares around the country, was occupied, disbanded by police forces, and occupied again. Support to the intermittents was ferociously encouraged from Nuit debout, and organizers from both movements offered their full cooperation to each other.

Through this coordinated action, as of April 26, the intermittents had occupied some of the most important public theatres in France: the Théâtre de l’Odéon, Théâtre National de Strasbourg, the Centre Dramatique National (CDN) de Bordeaux, CDN Caen, CDN Lille (also known as the Théâtre du Nord), CDN Montpellier, and eventually the Académie des Beaux Arts de Paris and the Comédie Française, amongst others. These occupations did not last for longer than a week, but their action was central to reframe negotiations with the French government, and they set a strong and untraditional precedent for what a “public” theatre might mean.

The Public

Public sites of cultural production, such as theatres, have a long history of political engagement in France. May 1968 marked the wide scale protest of the second half of the twentieth century in Western Europe. That movement (now a legend and a reference of social protest for young generations in the region) stemmed out of public institutions such as Sorbonne University or the Cinémathèque Française. At that time, the paradigm of public, widely accessible centers of cultural education and production was being rethought, still constructing itself, and questioning its own mission and political space. The shaping of public theatres became a political revolution in and of itself, hoping to create a space of openness through artistic practice, which would allow for an intermingling of social classes, ideological stances, and aesthetic understandings. This notion becomes apparent in the decisions that some directors of public institutions took at the time, such as on the night of May 15, 1968, when the Odéon Theatre, again the main focus of the 2016 protests, was occupied after Managing Director Jean-Louis Barrault opened its doors to the protesters.

Nowadays, the marriage between performance arts and the state, which promised itself as the delivering force of social and discursive equality, seems to have failed. Public theatres and dance centers in France have become institutions of success. Most funding for the arts in France is found, precisely, in those public, thoroughly institutionalized state-owned spaces. Success, in the artistic sphere, is often measured by the extent to which an artist’s work is shown or produced in such spaces.

The intermittents’ occupation of multiple public theatres across France became not only a social protest, but also, in its performative form, a sharp critique to material, ideological, and aesthetic understandings of both the “public” and the “political.”

As such, artistic innovation in France is now thoroughly state-directed and, following what appears to be a trend in European contemporary theatre, remains centered on bare-stage plays, performances, and choreographies that treat “meaning” as a profound yet apolitical object. Within this context, even political theatre, including documentary practices, becomes itself imbued in an essentialist discourse about the nature of human suffering, positing a hyper-simple space of empathic connection with the oppressed. The only political theatre that has a space in such public institutions is the one that speaks outside itself, that aims at a condensed narration of the other, and ends up commoditizing social conflict as it simultaneously cleanses it out. “The world is yours,” claimed an ironic installation signed by Claude Lévêque, on the Odéon theatre’s roof during the occupations of 2016.

It is in this context that the intermittents’ occupation of multiple public theatres across France became not only a social protest, but also, in its performative form, a sharp critique to material, ideological, and aesthetic understandings of both the “public” and the “political.”

Seeing the general assemblies of the intermittents as a site-specific form of performance allows us to envision a better paradigm of political theatre.

An Institution of Critique

Internally, the occupations generated spaces that could give place to direct, participative processes for political organization. In that sense, the general assembly I attended on April 18 prefigured the intention of the occupations—it posited its own desired formal outcome. The occupations that followed aimed at preserving this space, and expanding it, in order to keep on resisting the government’s intention to modify the intermittents’ status. From that “space of difference” in relation to the state, the intermittents could continue to plan actions, discuss terms amongst themselves and strengthen the affective links within their own circle, which they could not have done anywhere else. In my case, having newly arrived in France, it was the first time I was able to encounter a community I felt a part of—even if my legal status is not even close to that of intermittence. A lot of the occupied theatres did indeed host meetings inside them, and in cases such as the Odéon, which was continuously surrounded and locked by armed policemen, meetings were held outside of it, in conversation with those inside through balconies and loudspeakers.

Yet most importantly, seeing the general assemblies of the intermittents as a site-specific form of performance allows us to envision a better paradigm of political theatre. During the occupations, these spaces strategically altered what the theatre shows. Every day, as a show of support, sympathizers assembled statically outside the locked-in theatres, asserting themselves as a political group and allowing for the labor done inside those theatres to emerge into visibility. Moreover, the occupation prevented programmed performances from occurring, stating the importance of their labor rights above the product of that labor. This performance, the intermittents posited through their gesture, a performance that allows for both the buildings and the labor done in them to be seen under a different, more potent light, needs to precede all others.

“It's not a question of being against the institution: We are the institution. It's a question of what kind of institution we are, what kind of values we institutionalize, what forms of practice we reward, and what kinds of rewards we aspire to,” says Andrea Fraser in her essay From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique (2005)—a crucial reference in what has come to be known, in museum-based arts, as “Institutional Critique.” During that occupation, the political desires of those conforming these theatrical institutions came to the forefront—as opposed to the political aims of those directing them. In their performative act, they both presented and transformed the reality of the theatre through precise strategic alterations: the stage remained the center of the action, the organizing principle of the event, yet the public became a true co-creator of what took place on those stages (both inside and outside the theatres) by use of their bodily presence, their moving arms, and their newly-voiced discourse. Most importantly, the content of what was being spoken did not refer to a sort of inquiry into the human soul or an external social circumstance. The event inquired into itself: the theatre was discussing itself onstage in its materiality, its legality and its position relative to the state. Institutional Critique, which has seldom found its place into the theatre and often been displaced by documentary practices narrating foreign events, was taking the center stage.

Within that confined space of occupation, the intermittents were positing a new kind of political theatre that instead of commoditizing social conflict, instead of searching outside itself for its critical interventions, analyzed its own inner workings, both material and ideological: a theatre that arises as an “Institution of Critique.” Mapping out a circuit of political desires, French theatremakers, technicians, and choreographers took it upon themselves to explore and dissect the elements that conform their lives. What more can be desired from the public?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here