A Major Challenge of Being an Emerging Artist

It’s 7:30 a.m. I’m on the train going to work and I’m doing what every other commuter is doing: scrolling through Twitter. I’ve spotted a job opportunity on my timeline and retweeted it—yes, to share it with others who might be interested, but also to bookmark it so that I can return to it later. It’s an opportunity to create a theatre piece with a collective I admire in a performing arts institution I’ve never worked with. A quick glance tells me the application form isn’t like all the others: it’s a short set of fun, creative questions, which I mentally curate the answers to on my way into work. It’s also paid. Paid! I revisit the posting later only to find at the bottom of the page, written in small font, bolded, and with harsh italics, the dreaded words: For 18–25s only.

In the UK, where I’m based, there are many opportunities outside of formal education dedicated to supporting the early stages of a creative career. From long-running institutions like the National Youth Theatre, which nurtures young actors, to programs offered by theatres and arts organizations, such as introductory playwrighting courses or young company ensembles, these opportunities exist to provide access, encouragement, and education to young people within an industry that is notoriously difficult to get into.

The common factor between many of them is that they are created to support “emerging talent.” Which means what, exactly?

What once was 'Will you apply again next year?' quickly became 'Grab every opportunity while you can, it’ll be much harder after you turn twenty-five.'

My definition of an emerging artist is a creative practitioner—be it actor, director, designer—in the early stages of their career, perhaps with some professional credits, who has been working within the industry but isn’t yet recognized as an established artist in the public eye.

Of course, if we want to get arty about it, we can say that artists are constantly emerging. But if we are to look at the platforms that aim to support “emerging talent,” many of them stipulate that applicants must be aged between eighteen and twenty-five—sometimes thirty. Thus, it appears as though the industry defines “emerging” as synonymous with “young.”

In my early twenties, I was fortunate to have participated in programs for emerging artists. I learned new skills, acted in productions, and collaborated with top industry professionals. I took advantage of opportunities to perform my own writing, which sowed the seeds for me wanting to create my own work. These experiences—both the positive and the less constructive aspects of them—shaped my interests and gave me confidence to pursue a career in theatre.

But then I turned twenty-four. The conversation started changing. What once was “Will you apply again next year?” quickly became “Grab every opportunity while you can, it’ll be much harder after you turn twenty-five.”

And then I turned twenty-five. I was grateful and relieved that a lot of programs had been extended to twenty-six-year-olds, some even to thirty-year-olds. But, in reality, the conversation hadn’t changed. Nothing had changed; the goalposts had simply moved. I was constantly reminded that youth is a currency and I had to spend it wisely.

As I approached the upper age limit it felt wrong to follow the advice of “apply for everything while you still can.” I didn’t want to ride the emerging-career carousel forever, I wanted to progress forward. I wanted to apply and develop the knowledge and skills I had emerged with.

It’s naive to expect to become an overnight recognizable artist through these programs; that’s not what they are for. But I felt a pressure, perhaps even an expectation, to hit some sort of invisible jackpot. Did I only have a few short years to prove my worth and work ethic, to demonstrate some outstanding talent that would surpass my age so that I would be remembered before I would fall dramatically short of opportunities and professional support?

If the ideal linear journey of a career in theatre begins with emerging, then mid-career, and onwards to established, then it’s clear that theatremakers need development opportunities to support them along the way. In order to continually develop our practice in a constantly changing industry, we need safe spaces to repeatedly learn, create, try, and fail.

Without industry-led developmental constructs aiding artists beyond emerging status, we begin to lose them. London-based artist Paula Varjack told me that when she was researching her show Show Me the Money, a multimedia performance exploring the difficulties of making art in the current economical climate, she found that “[age] thirty-five was a watershed moment for many artists, when [they] stop and give up.”

It’s also worth noting that one of the issues with age limits on programs is that they don’t allow for people who discover their creative ambitions later in life. They assume that everyone who wishes to pursue a creative career is not only able to realize this at a young age but to act upon it then too.

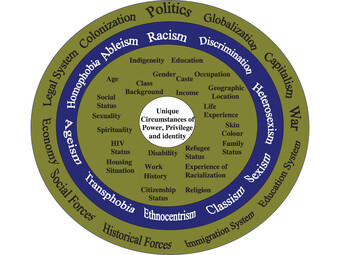

The difficulty of supporting and providing progression routes undoubtedly affects the stories being told and by whom. At a time when creative industries are consciously moving towards representation and inclusivity, it is vital to enable access to underrepresented voices who have been muted by the industry for so long. Yet how can we be open to them if we are only able to hear them at the early stages in their lives? How can we expect to see diversity in our theatres and arts organizations if we only provide initial access but little nurturing or development opportunities?

I revisit the posting later only to find at the bottom of the page, written in small font, bolded, and with harsh italics, the dreaded words: For 18–25s only.

Thankfully, things do seem to be moving forward. In March 2018, Arts Council England (ACE) launched Developing your Creative Practice, a fund that empowers individual practitioners with the financial security to assess and develop their craft, regardless of where they are in their careers.

As is explained on the website, the fund will create “more pathways for individuals looking to make a change in their practice and ensure excellence is thriving in the arts and culture sector.”

After much research and discussion with arts organizations and individuals, ACE was reminded that supporting artists at a critical point in their careers would likely lead to a significant long-term return. “It will help to encourage innovation, enhance quality and build a deeper, more diverse talent pool,” says deputy chief executive Simon Mellor in a blog post, before elaborating further: “We recognise that substantial changes can happen at any point in a career, so there are no upper age restrictions.” The fund provides individual artists with financial support, practically buying time for them to experiment and concentrate on their career development.

It must be noted that there are other programs that have been set up by industry bodies that also provide career support. For instance, Stage Directors UK offers a mentoring program for mid-career directors, pairing them with experienced directors who provide support and guidance. It’s noticeable that the criteria is based on professional experience rather than age, creating a level playing field. There is even a database that lists funding opportunities in Europe, which helps artists find resources to cultivate their practice and collaborate with others. While criteria for each opportunity varies, there are many that also rely solely on professional credits.

Though it’s encouraging that these funds are being set up and that these opportunities exist, we must also ensure that participants of existing programs are supported after they have “emerged.” After all, what theatre or organization wouldn’t want to aid the progression of talent beyond the remits of its own programs? Participating artists must be granted something beyond the epithet “former young company member.” I have experienced firsthand the difference it makes when an organization offers some form of aftercare to its graduating participants. Whether it’s reading scripts, offering rehearsal space, sharing opportunities, organizing meetups, or simply instigating a catch-up over coffee, it’s important that these relationships are cultivated and not solely pursued by the individual artist.

If industry bodies in the UK are going to provide opportunities for “emerging” talent, then they must not neglect artists who exceed an age limit—and they must not forget artists who embark on their creative ambitions after they have passed a certain age. There needs to be room for investment in artists of all ages so they can continue to progress throughout their careers, build relationships with audiences, and create ever-interesting work for the community—rather than simply emerge.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

If "the industry defines 'emerging' as synonymous with 'young'" perhaps we old may be considered submerging.

It's hard not to be cynical. With the run we've had in Chicago—Profiles Theatre, Dead Writers Theatre, Dream Theatre Company, Writers Theatre—of theaters either closing shop or threatened with boycott amidst harassment allegations, you wonder how much "emergence" into a theatrical career is contingent upon acquiescing to extra-professional demands.

The budding artist can hardly expect support, but all workers deserve "safe spaces" of employment. (A documented on-the-job show-biz harasser was elected president of the US, his improprieties widely lauded as perks of privilege, which bodes badly for the creation of such spaces.)

Thank you for discussing this problem with such clarity. This does not

pertain only to the theatre world. Composers of concert music face the same issue, and I assume that practitioners in other areas of the performing arts would say the same thing.