I spent much of my childhood disappointed to be from Tulsa because it wasn’t important in the grand scheme of things in America—it was never the setting for movies, it was never in the national news. The only time it was ever reflected back at me was in Oklahoma!, which I saw every summer at an amphitheatre just outside Tulsa called Discoveryland—a tradition for many Oklahoma families. I have no memory of a black actor ever playing one of the named roles, and any black actor in a smaller role had to assimilate surrounding white cultural portrayals.

Even though the depiction on the Discoveryland stage was not my reality, I clung to it because it made me feel relevant. As I got older, I recognized that Oklahoma! was the only depiction of my home and its theatrical popularity had defined the state and my identity to outsiders. When I moved to Massachusetts and strangers heard I was from Oklahoma, as if on cue people burst out with “Ooooooook-lahoma!” and ubiquitously knew no other lyric. People asked if we had anything other than dirt roads and cows. I sighed, but settled for fitting somewhere into America’s story.

The Tulsa I was discovering did not want to be defined by its rich black history. It preferred the Rodgers and Hammerstein version.

Ten years later, still living in Massachusetts, I read about Tulsa’s buried history: Black Wall Street, Greenwood, and the Tulsa Race Massacre. The story of the city’s Greenwood neighborhood is so admirable and newsworthy that I was shocked to discover it existed in Tulsa and I had never heard about it. I was further shocked to read that it had been destroyed overnight by white people and that the atrocity had been covered up for nearly a century. Upon further investigation, I learned that very few people, black or white, knew about what seemed obviously important American history. For a city with no national identity, other than being famous for oil at one point, shouldn’t Tulsa be proud to shout from the rooftops that it housed Black Wall Street or take national ownership of its shame in destroying it?

I did not want to admit to myself that a different cultural identity was emerging from the one I had been presented with year after year in the famed musical. The Tulsa I was discovering was racist and silent against oppression. The Tulsa I was discovering did not want to be defined by its rich black history. It preferred the Rodgers and Hammerstein version. When I tried to broach the topic with family or teachers, white responses of obliviousness or defensiveness resounded. No one said, “Well, Tulsa was home to the richest, most supportive black community in the country and then, in 1921, ten thousand white people crossed the railroad tracks into their neighborhood and killed over three hundred black people and burned their homes and businesses to the ground overnight and the mayor of Tulsa told everyone to remain silent about it a week later, so, that’s what we do. We obey our authorities and remain silent.”

Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical takes place in 1906, before Oklahoma came a state, before white founders separated Native Americans from black people from white people, before Tulsa fully became the “oil capital of the world.” Therefore, the musical takes place as the Greenwood area of Tulsa was growing and booming, parleying with farmers from neighboring black towns like Muskogee, Vinita, Rentiesville. For many Tulsans, Oklahoma! defines our state’s founding as all-white when, in actuality, the state fostered more all-black towns than any other in America’s history. In fact, according to local newspapers at the turn of the twentieth century, many residents believed it was on its way to becoming the first all-black state in the country. In her memoir belonging, a culture of place, bell hooks talks about how post-slavery migration to northern cities severed black people’s connection with the land, which was traumatic to black identity. This connection was not severed for those migrating to Oklahoma. Here, they maintained their agrarian roots while having the freedom and opportunity to grow their own businesses and own their own land. For this reason, black people called the state the “Dreamland.”

They played the roles as they knew them in their bodies because Oklahoma! was their history.

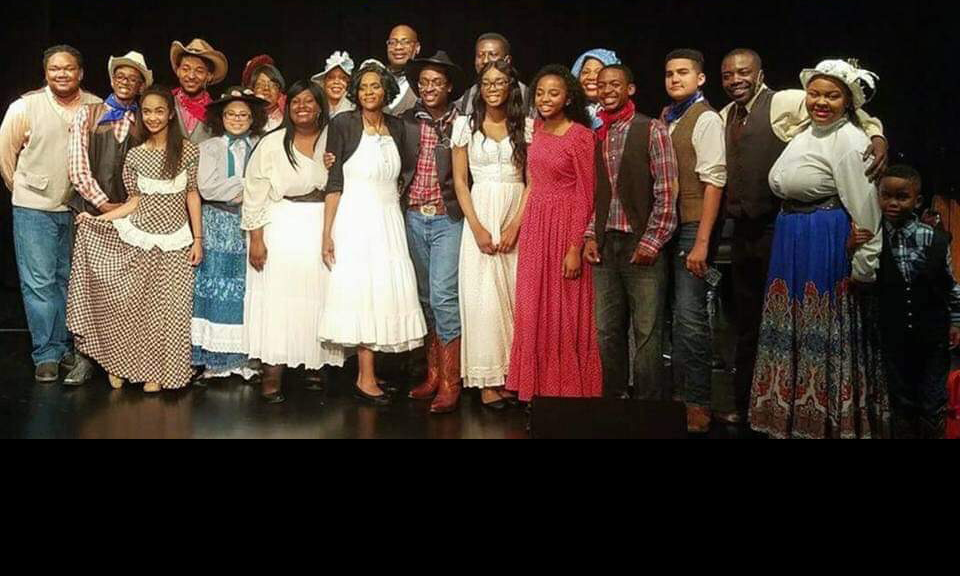

As my interpretations of Oklahoma!’s iconic characters had been limited to their white definitions, I was curious to see Miller Dill’s production. I wondered: Who would the audience be? How would they receive the show? Was the director planning on just placing black bodies into the traditional white roles, some of whose characterizations could come across as insulting to black people? But it was clear from the start of the show that I had fallen under the spell of whiteness, assuming these characters were white and that black actors would have to comparatively play them as such. The actors taught me differently. They played the roles as they knew them in their bodies because Oklahoma! was their history. They were telling their own story, the truth of black communities before segregation in Oklahoma. Beyond presenting fully realized characters, as opposed to stereotypes, Spinning Plates removed a monolithic portrayal of black culture.

Ado Annie was not ditzy or overly sexualized as I had seen on stage so many times before. Jen Thomas portrayed this woman as proud of her physical assets, unapologetically owning her freedom to choose men she wanted to be with. Her performance made me feel ashamed of my own absent feminist eye in viewing previous Ados. Nash McQuarters’s portrayal of Will was not that of a dumb kid who couldn’t add or subtract, but of someone who was savvy enough to know that he should invest in skills he did have, like cow-roping, because those would advance him in life. Cornelius Johnson’s cocky cowboy Curly was on the threshold of a dream becoming a reality, and Phena Hackett’s Laurie was reminiscent of farm women who had life responsibilities on their plates and were in no rush or need to marry. These actors showed an innate understanding of Oklahoma’s historical identity.

The characters of Jud and Ali Hakim presented a nuanced peek of the complexity of Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood, complete with hierarchy and international allure. After the massacre in 1921, a few of the wealthier black survivors blamed the atrocity on some of their own people, the “bad negroes.” Even in Greenwood, where Black Wall Street was famous for its collaboration and communal support, there were outcasts like Jud (played thoughtfully by Booker Gillespie). The historical intricacies of navigating through people’s various places in this new land came through in Spinning Plates’s production. Durrell Ousley-Wray comically portrayed Ali Hakim as from the famed Wakanda instead of from Persia, which removed the awkward othering that often takes place with community depictions of Hakim. Here, Ousley-Wray’s portrayal reinforced the fame Tulsa had in black communities even across the ocean and added great humor to how a Wakandan might view the new beginnings of an American state like Oklahoma.

The ballet brought into focus an even more layered identity of black lives in turn-of-the-century Oklahoma.

The connection of Oklahoma black people to their African homeland thrives today in North Tulsa and this was most prevalently seen in the production’s iconic mid-show ballet, performed and choreographed by Oti-Lisa Brown. The ballet brought into focus an even more layered identity of black lives in turn-of-the-century Oklahoma because Brown’s dance evoked a story of Laurie’s ancestral journey as African, slave, and now African American living in promising Oklahoma. As Laurie fell asleep on stage, Brown appeared as Dream Laurie in full Gambian dress and head wrap, accompanied by African drummers. Brown danced a dance of Senegalese infusion, which she described as “showing the rites of passage for young girls entering womanhood.”

It was celebratory and confident, but soon turned frenzied as her head-wrap ripped off, skirt tore, top flailed—all of which conjured images of violent and violating kidnappings from African shores. Slowly, Brown’s body morphed into a controlled, rigid dance, sad and uncertain, stirring up for me as a viewer the experience of slavery. She later told me she used dance moves from “Manjani,” a celebration dance, and from “Sinte,” a dance in which “you also ask for the wisdom of the ancestors about the future.” Brown’s piece ended with a sense of settledness, which I surmised was about the migration to Oklahoma. Her final movements presented hope and fear, as if foreshadowing 1921. Even a presumed free existence in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the “brand new state” that was “gonna treat you great,” carried with it the cognizance that no place in America is truly a dreamland if you are black.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here