“There is no Roma theatre, and there are no institutions, there is no anthology of Roma drama, and there are no publishers. We are not present in education, and if so, we appear as victims or criminals. This is not okay.” – The Independent Theatre

While reflecting on Roma presence in Hungarian theatre, I think of the phrase by Budapest-based journalist Imre Déri from 1912: “The old patriarchal relationship between the Gypsies and the gentlemen merry-makers.” Both historical and contemporary representation of Roma, which are grounded in escapism and nostalgia, have been constructed and negotiated under emotional and highly nuanced circumstances, including political animosity towards Roma by the Hungarian population and the scapegoating, institutionalized anti-gypsyism, and hate crimes against Roma.

In spite of being the biggest minority group living in Hungary, Roma people are rarely represented in theatre and other arts, and when they do appear in literature or on stage, the way they are depicted—exotic primitives, leading romantically wild and unrestrained lives—often enhances the existing anti-Roma prejudices.

The way Roma are represented exposes the conjunction of ideology, power, and aesthetic fundamentals in Hungarian theatre, while pointing to the political potential connected to this discriminatory regime of representation. This situation can be ascribed to Hungary’s past (anti-Roma laws securing Roma in the Habsburg Empire in the eighteenth century, anti-Roma discrimination in the inter-war period, and the Holocaust of Hungarian Roma in the twentieth century), as well as to current Hungarian affairs and social tensions (state-authorized anti-gypsyism and discrimination).

The Time of the Gypsies

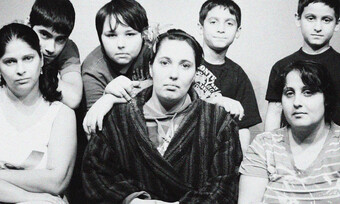

In an era of growing nationalism and anti-Roma hatred in Hungary, which culminated in a series of racist murders in 2008 and 2009, the discussion about the play Cigányok (Gypsies), produced in 2010 by Budapest’s József Katona Theatre, has served as a turning point around the possibilities for effective representation of Roma (and other minorities) in the mainstream culture and has raised burning questions concerning the social responsibility of art in the context of shrinking public space.

Following the premiere of the play, the Roma and non-Roma actors and students of the educational program run by the Independent Theatre accused Gábor Máté, the director, of disseminating stereotypical depictions of Roma. Penning an open letter, the authors argued that in a public sphere where minority identities are deprived of any appropriate “speaking positions,” theatremakers should strive to create representations of Roma that help dismantle existing stereotypes rather than reinforce them. The critics of the play contended that what makes stereotypical depictions especially damaging is that, because Roma have extremely limited visibility, the play might be all some audience members know about contemporary Roma. The authors of the letter also argued that the play could have benefitted from involving Roma artists in the creative process.

While Máté’s reply might have been dismissive or even disrespectful towards the authors of the letter, the exchange was a very important push to inspire debate about the representation of Roma on the Hungarian stage and the role of the arts and culture in general. The director, who is also the artistic director of the institution that produced the play, revealed himself as a guardian of conservative, modernist rubric, armed with two effective tools that help enforce the stability of theatre as colonial institution: the insistence on division between private and public, and the refusal to use theatrical representation to expose strategies and relationships of power present in contemporary society.

These seemingly transparent but ideologically extreme instruments of control and power are conveniently underspecified and always ready to be used, and serve to keep theatre in the safe, inert realm of high art, presenting works that are self-reflexive and separated from reality. Thus, according to the modernist rubric prevalent in Hungarian mainstream theatre, in order to represent social conflicts, theatre must be divorced from actual experience and real political space.

Roma characters have rarely been centered as main plot points or protagonists, but rather have been momentary asides, adding a touch of the exotic to plotlines centered around ethnically Hungarian protagonists.

A Roma Who Cannot Play Violin Is No Roma

Since their first official appearance in a Hungarian-language play in 1750, Roma characters have rarely been centered as main plot points or protagonists, but rather have been momentary asides, adding a touch of the exotic to plotlines centered around ethnically Hungarian protagonists. But in early literary appearances, Hungarian Roma were consistently portrayed as fiercely independent and musically gifted, often dancing and playing violin.

Close reading of eighteenth-century Hungarian drama reveals that the majority of the representations of Roma are mediated through depictions of musical performance: their interactions with gadje (from Romanes: a non-Roma, a non-Romani person) are primarily related to performative transactions, like in Kristof Simai’s play Váratlan vendég (Unexpected Guest, 1750), where a couple of Gypsy musicians, Fulak and Lestar, are haggling the price of their performance. Castle records from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries prove that members of the Hungarian ruling class employed Roma as entertainers, and being a musician automatically improved the status and elevated a Roma in the eyes of gadje.

According to critic Anna Szollossy, the main characteristic of Hungarian representation of Roma is their function as comic relief. Szollossy’s analysis of representation of Roma in Hungarian literature also mentions a few Roma truth-tellers, including Mihály Csokonai Vitéz’s heroes Szuszmir (A méla Tempefői, 1793) and Antal Buga (Gerson de Malheureux, 1795). There is also a tendency in Hungarian literature to cast Roma as coryphei of democratization, who appeared in folk drama of the nineteenth century. The trend to cast Roma as either musical jesters equipped with comic force or avant-gardists of democratic ideas was in contrast to foreign, especially German-language, representations of Roma, which fed into romanticism and sentimentality. It was also German-speaking texts that led to the proliferation of discriminatory stereotypes of Roma as lazy and horse-thieving rogues in theatre and other arts.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here