Power! Stokely Carmichael at the Capital Fringe

The Capital Fringe, in its tenth year, is the second-largest fringe festival in the country, with 129 groups performing this year. Meshaun Labrone’s Power! Stokely Carmichael is one of the festivals most thought-provoking and relevant solo shows. This is the kind of play that a fringe festival is made for—well polished, low budget, and unafraid to offend.

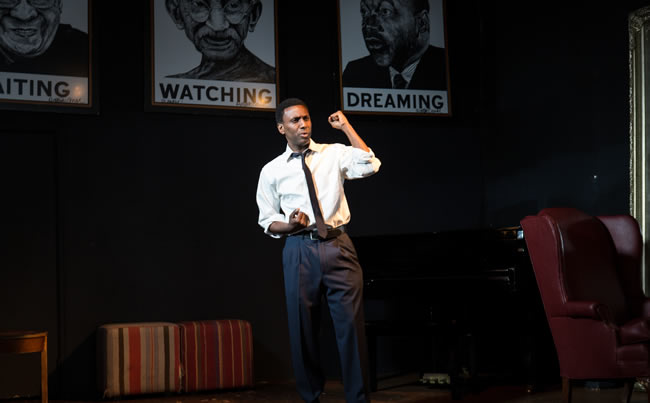

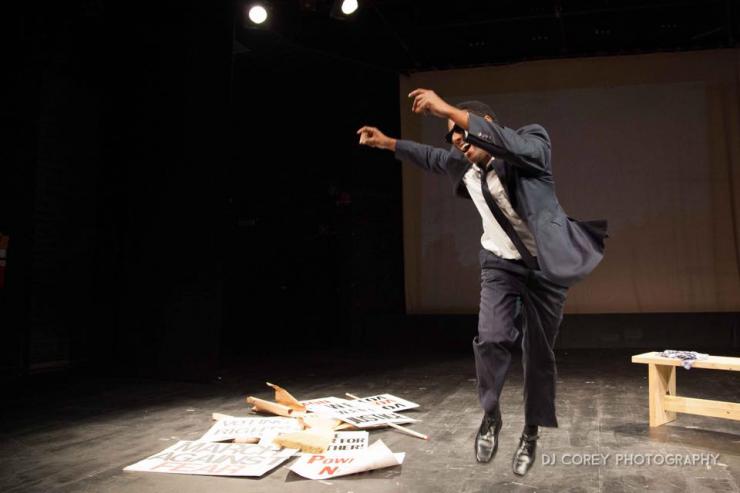

Other than a screen, the set includes only a bench and a pile of protest signs. Director Jennifer Knight keeps Labrone moving and the action clips along at a good pace. For a riveting hour, Labrone, as Stokely Carmichael, the legendary civil rights activist and founder of the Black Power movement, speaks about Black oppression, white denial, and the need for change. Before the lights go up, images of civil rights demonstrations and protesters under attack roll across a screen at the back of the stage. Labrone enters, dressed in a suit and tie, stands on a bench, and addresses the audience as though we were gathered to undertake a march. “There will be blood,” he says. “If this is too much for you, you can leave.” Besides creating suspense, the statement is fair warning. Much of the play is about the bloody history African Americans have suffered. The truths Labrone lays bare are not easy to confront, but his skillful presentation of the material allows the audience to be shocked and horrified and at the same time to stay curious and receptive.

The truths Labrone lays bare are not easy to confront, but his skillful presentation of the material allows the audience to be shocked and horrified and at the same time to stay curious and receptive.

Labrone’s Stokely, quoting from one of Carmichael’s actual speeches, says, “For nonviolence to work, your opponent has to have a conscience, and the United States has no conscience.” In the narratives that follow, Labrone supports this point. Carmichael relates his encounter with an old man, Cleo, who works in a diner and witnessed a lynching when he was a boy. Labrone, a formidable actor, effortlessly steps into the character of Cleo to relate the details of the lynching. The story, which is true, is horrifying: Sam Hose was murdered in Georgia in 1899, after killing his white employer in self-defense. Hose was accused of killing the man as he ate his dinner, then raping the white man’s wife, an account that the wife—after Hose’s lynching—would refute. Hose first was tortured. His ears and fingers were cut off. His genitals were cut off. His face was skinned off. Then he was burned alive. As Cleo finishes telling the story, we hear Hose’s screams, loud and anguished.

Cleo’s family left Georgia for Mississippi. “It wasn’t no better here,” Cleo says. He cites the murder of Emmet Till. A photograph of Till in his coffin flashes up on the screen, his face horribly disfigured.

Labrone, as the old man, sweeps the diner floor and recounts how the owner is raping his nieces, one by one, as they come into their teenage years. Labrone switches to the character of the white diner owner, angrily accusing Cleo of having an angry expression on his face. Cleo cowers, denies it, and says he is perfectly happy.

Cleo continues sweeping as a recording of one of Stokely Carmichael’s speeches plays over the speakers.

One of the strengths of Labrone’s play is that it is completely unpredictable. What will come up on the screen or over the sound system next is impossible to guess. What character Labrone—or Stokely Carmichael—will step into next is unforeseeable. The play’s most intense moment features Carmichael representing a man on his knees, praying to God, who, Carmichael remarks, is portrayed always as white. “I think we’ve been saying the wrong prayer,” he suggests. “Is that the prayer of the loving disciple to the master teacher, or of the slave begging his tormentor to stop?” Over Stokely’s prayer, half-sung, half intoned, is the loud and repeated sound of a whip cutting the air.

Labrone stands, and James Brown’s “I Feel Good” rings out. “Someone in the crowd has brought a radio,” Labrone says. He proceeds to riff on James Brown, how his music is power in your bones, and then he does a startlingly good and agile bit of dancing. The effect of these quick and unpredictable changes is dizzying. The audience is kept off balance. The result is that, in spite of being a play full of opinions, Power is never tedious or preachy. We are on the edge of our seats, waiting to see what’s next.

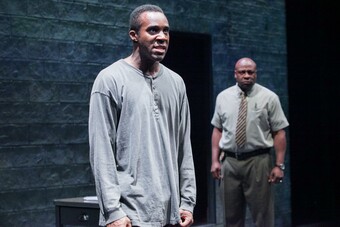

Certain incidents in Stokely Carmichael’s life make their way into the play, like registering Black voters in Mississippi with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the members of which were armed with rifles for self-defense. But the focus is not on Carmichael’s life. Rather, it is on his position that violence is sometimes necessary, a position Carmichael adopted shortly after assuming leadership of the SNCC in 1966, when one after another civil rights activist was killed.

Labrone illustrates the argument for self-defense with an anecdote. Suppose you’re white, he says, and your mother invites a Black man over for lunch. “Leave it to Beaver” music cranks over the speakers as Labrone acts the part of flustered hostess. She serves chicken that is too spicy. The luncheon guest yells at her, slaps her, and punches her. You, her child, cannot defend her because you’ve taken a position of nonviolence. You can only pray for her. Then your father comes downstairs and the guest hits him over the head with a chair. You call the police. When the police arrive, they ask your mother why she served such spicy chicken; serving spicy chicken, they argue, technically is assault. The police handcuff your father and your mother—the only two people who are injured—and haul them off. The guest goes free. This is how the police and the criminal justice system treat African Americans, Carmichael suggests. Even if they raise their hands in self-defense or remain entirely nonviolent, the blame will fall on them.

Carmichael asks a trenchant question. “Do white citizens believe in nonviolence, or do they believe in silence?” An accomplice can go to jail, he reminds us, just for being there and remaining silent when a crime is committed. “We are surrounded,” his Stokely says. “Black people are surrounded by our murderers and their quiet accomplices.”

The subject shifts to a theme central to Stokely Carmichael’s teachings—the way African Americans see themselves needs to change. Labrone imitates a dorm mother at Howard University, speaking to a young female student: “It’s bad enough that you are Black as midnight, do you have to show off all your ugliness? Why don’t you get yourself a nice, silky smooth, flowing synthetic up do wig like me. . . . You are going to spend your days Black, proud, nappy, and alone.”

He goes into the audience and takes a woman by the hand, inviting her onto the stage. “Black woman queen coming through,” he says. He recites a poem in praise of her. “That is what we should be saying to the sisters. Go home and tell your sisters and daughters that they’re beautiful.”

In an allusion to the Bible story where Jesus is tempted by the devil, Labrone’s Stokely holds a baby, showing the baby all that can be his. “White supremacy,” he says, “is the devil of humanity. It takes all the little white babies to the mountaintop, tells them, ‘Look, little baby, as far as the eye can see, this is your inheritance: wealth, people, dominion.’” Labrone slips into baby talk, which provides a welcome laugh. “Never share your wealth and never see them as equall . . . You forfeit the kingdom, little baby.”

He argues that there is a place for white people in the struggle for justice. It involves going into the places where white people tend to have access, the places of power. “You can uproot white supremacy and plant seeds of justice,” he argues.

Stokely lies down against the bench and dreams he’s a dog.

Beg! Says voice of white woman.

“We want jobs!”

Say I love you.

“I love you!”

Want a treat? A good government job! Open, open, wider, wider!

The dog is knocked down.

“Where’s my humanity?” Carmichael asks. “What if liberation doesn’t come?” His greatest fear is that he will spend a lifetime of days as an elite, upper-class slave. Material success is not the same as freedom.

We are back at the march. The police have arrived. “We have to stand up against them,” Carmichael says. “You want to pray?” Stokely says that if so, this is the prayer we must pray, and he launches into Psalm 109, a prayer for aid against and vengeance upon the oppressor:

Hold not thy peace, O God of my praise;

For the mouth of the wicked

and the deceitful have spoken against me

with a lying tongue,

and fought against me without a cause.

When he shall be judged,

let him be condemned:

and let his prayer become sin . . . .

The play doesn’t end there. Images of lynchings flash up on the screen. Tamir Rice, smiling; a photo of a white police officer with his knee in the back of a fourteen-year-old, bikini-clad black girl in McKinney, Texas; image after image of lynchings, as well as photos of black women recently killed by police. Labrone ends with a quote from the Bible, God’s words to Cain: “What hast thou done?”

The play is powerful, disturbing, and important. Stokely Carmichael called for African Americans to abandon nonviolence to defend themselves… Power! Stokely Carmichael is not a call to arms as much as a call to consciousness and a call for change.

The play is powerful, disturbing, and important. Stokely Carmichael called for African Americans to abandon nonviolence to defend themselves. Later, he called for violence as a form of revolution. Power! Stokely Carmichael is not a call to arms as much as a call to consciousness and a call for change. Meshaun Labrone’s play could hardly be timelier. In spite of all the publicity surrounding police shootings of unarmed African American men and women, the shootings continue, with at least six in July alone.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here