Pulp Ibsen

Vive Le Genre!

For years, genre storytelling for the stage has been discounted and pushed to the wayside. It’s often deemed unable to compete with the “serious” storytelling capabilities of Realism. This series presents an overview of the rich history of genre theatre, which is broken down by category, and outlines the possibilities for Fantasy within the dramatic arts.

William Shakespeare was a liar. Sure, he had some interesting stuff to say about murdering your boss, or the dangers of premarital sex. However, when it came to theatre, honest to goodness, the guy had no idea what he was talking about: Hamlet famously says to his actors that “the purpose of playing” is to hold “the mirror up to nature.” Who does this guy think he is? According to Hamlet, playwrights and actors should strive to present their narratives sans superfluous exaggeration and sentimentality, which aspiring tragedians took to heart. We started printing this saying on t-shirts, and hanging it up in our high school drama classrooms. As playwrights and players, we made the mistake of associating realism with truth.

To be honest, it’s not Shakespeare’s fault. This sentiment is as old as theatre itself. Many classical authors have expounded on the idea that drama is only truthful when mimicking reality as closely as possible. Yet, by embracing this idea, we admit to its opposite by default and codify the many forms of fantasy as nothing more than whimsical, wishful thinking.

It’s high time someone highlighted some of the weirder classics that have stretched the limits of how fictitious our fiction can be.

Make no mistake: we’re living in a time that has no shortage of fantastic plays. However, we’re also living in a time that suffers greatly from a shortage of fantastic plays—pieces that play with the very fabric of the reality they’re representing to create a world free from the universal laws which govern our own Some of the most highly regarded plays of the last ten years that received Pulitzer prize nominations tell us a lot about what we hold in our artistic esteem. Plays like Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris, Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo by Rajiv Joseph, August: Osage County by Tracy Letts, and Ruined by Lynn Nottage do have fantastic elements, but they still deal with serious, realistic, social conflicts. This style reflects a realistic nature—a boring nature. A nature we often believe is our only option.

It’s rare for artists to be told they don’t have to hold a mirror up to nature, but it needs to be said. Fantasy in its many forms is culturally permissible in every other medium, yet onstage it’s brushed to the side. Imposing realism as the de rigeur style and subject for artistic success places an unfair burden on theatre-makers by setting them up for an impossible task. How can any individual expect a group of randomly assembled people to share the same truth, let alone reveal it to them? In today’s information age, it’s easy to think artists have to shoulder the weight of humanity’s daily problems because it’s easier to see them online. But should contemporary theatre-makers express themselves in the genre language of Spaghetti Westerns, or Magicians? They’re told that their work cannot contain truth as permanent as something that’s on a Facebook newsfeed.

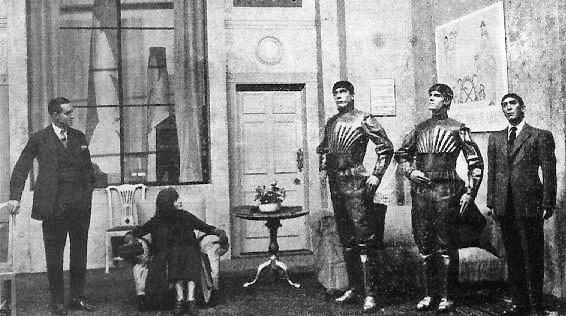

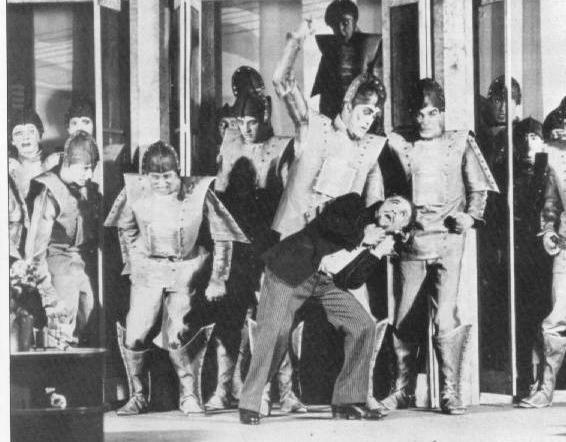

Permission to get pulpy shouldn’t be given by some guy on the Internet, but instead by the weight of a theatrical history we’ve conveniently forgotten. Artists operate on precedents, rebelling against, or supporting what came before them. It’s high time someone highlighted some of the weirder classics that have stretched the limits of how fictitious our fiction can be. These works can be of benefit to a generation who may not know that theatre can be just as wild as a blockbuster movie. If a playwright decides to try her hand writing Science Fiction, she should know about the origins of robots onstage from Karel Čapek, just as, anyone attempting horror should be familiar with The Grand Guignol.

If our fiction is realistic, our reality follows suite. Is this the world we imagine for our children?

Fiction is our birthright and our heirloom—the gift one generation gives another. We mold our world in the image of our imaginations. This is why we continue to marvel at Odysseus’s wit, Bond’s charm, and Elphaba’s courage generation after generation. While our lives endure, Hamlet will still direct his plays. If our fiction is realistic, our reality follows suite. Is this the world we imagine for our children? A boring world? An angry world? A sad world? Do we want our fiction to show a universe that can be completely moralized, analyzed, and worst of all, understood? Are we satisfied with our own imaginations being indistinguishable from the world we observe?

The information we’re given outside the stage transcends genre. There is no Science Fiction in the real world, only science. In our modern era, the idea of a genre theatre, such as the theatre of fantasy, has never been more important because it’s never been so rare. We as theatre-makers may not be obligated to reveal the truth, but we sure as hell are obligated to stretch the realms of possibility within our own imaginations. If we cease to represent the fantastic within our fiction, it will cease to exist.

This series is intended to be a kick in the pants for the theatre-maker that has been told the only way to access truth is to write a play set in a living room. It’s time we throw some dirt in the mirror.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I agree with so much of the spirit here, but have a hard time dismissing the great genre work out there. Can't we argue for the worth of our genres without downplaying the work that's already being done and the people dedicated to it?

Fun and engaging series, Jake! I´m curious about the title, "Pulp Ibsen". He´s an interesting and important writer, as the style and content of his plays is very expansive over his nearly half-century career. Before pioneering modern realistic drama with plays such as "A Doll´s House", "Ghosts", and "An Enemy of the People", he had written plays inspired by history written in classical verse (Catiline, the Vikings at Helgeland), as well as "poetic dramas" that were originally never meant to be staged, as they were considered impossible to interpret (Brand, Peer Gynt). Towards the end of his writing career, he shifted away from realism, with plays that became increasingly abstract or "dream-like" in style and content (The Lady from the Sea, Little Eyolf, When We Dead Awaken).

Hear, hear!

Writing Science Fiction and Horror plays right now and you are right--it has never been so exciting to write and imagine. Can't wait to hear about the many histories and plays in these genres you suggest in the series.