Pulp Ibsen

What’s Your Fantasy?

For years, genre storytelling for the stage has been discounted and pushed to the wayside. It’s often deemed unable to compete with the “serious” storytelling capabilities of Realism. This series presents an overview of the rich history of genre theatre, which is broken down by category, and outlines the possibilities for Fantasy within the dramatic arts.

We’re living, oddly enough, in a golden age of Fantasy. Never before has the genre been so popular, reaching across so many mediums to engage those who never knew how much they loved wizards and dragons as much as the next guy. While Game of Thrones and Outlander provide us with hours of entertainment across mediums, Fantasy has seemingly become unstuck from its natural habitat: the stage. One might ask, “Fantasy onstage?”, while performing a spit take from their goblet of mead in disbelief! “From where does this come, and why is there not more?” Worry not noble traveler, for the answers lie in a tale as wretched and exciting as the very outlandish sagas we now hold so dear to our hearts.

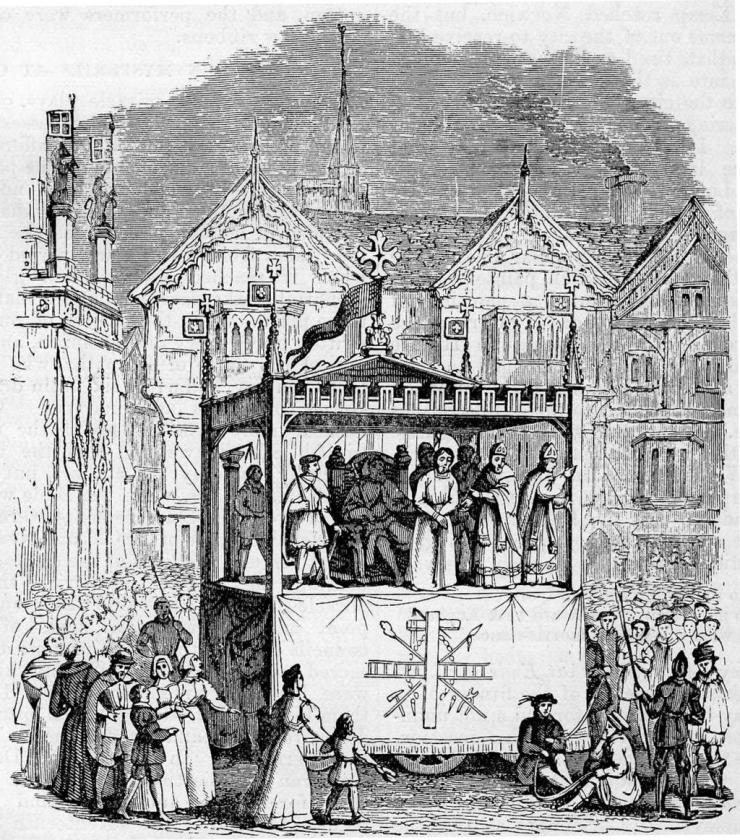

While classical western theatre is replete with fantastic stories (just think of Medea and her dragons), very little of the magic that enthralled the ancient Greeks and Romans carried over into the theatre of the Middle Ages. Mystery and Miracle plays, firmly under the control of the Catholic Church, placed emphasis on representation of the Biblical Miracles and not Pagan subjects that were deemed perilous to the soul. Yet, ironically, it was in the Middle Ages that the idea of modern western Fantasy as a genre began to emerge. Groups began to form around certain motifs defined as the fantastique when Frankish, Germanic, and Celtic myths were translated from religion into popular folklore. It was within the confines of the fantastique that many beings, such as witches, fairies, and characters like Harlequin and Oberon were given their definitive forms. However, it wasn’t until the Renaissance and the rediscovery of Aristotle’s Unities in Italy that theatre began to move beyond the control of the Church and back into the realm of the strange. Renaissance authors found their audiences natural beliefs in the supernatural rife for exploitation. Acts of fate, like those caused by the Weird Sisters in Macbeth, Prospero in the Tempest, or Doctor Faustus in Marlowe’s play, were widely considered to be real.

One wonders, in the post-Tolkien era, where is the adult Fantasy for the stage? Who will take up the mantle, passed from MacDonald to Moorcock to Martin?

Paradoxically, the magical influence on the theatre of the Renaissance was also deeply rooted in the intellectual developments of the time, one example being the rediscovery of the Roman engineer Vitruvius, whose catalogue of ancient technologies captivated alchemists like the famous John Dee, who was responsible for the construction of a flying bird with a man on its back for a production of Aristophanes’ Peace—one of the first “magic” devices in English Theatre. While the device by our modern standards would be considered primitive, it stunned Dee’s audience and earned him the reputation of a magician, a label that stuck with him for the rest of his life.

While theatrical machinery became more popular under the funding of Elizabeth’s successor, James I, it still wasn’t met with universal popularity. The playwright Ben Jonson hated “magical” theatrical devices because he saw them turning theatre into cheap, trick shows. In response to the architect Inigo Jones’ machines, Jonson wrote “He designes, he drawes, he paints, he carues, he builds, he fortifies, Makes Citadels of curious foule and fish...He has Nature in a pot!”

As the Renaissance ended and the Enlightenment began to pick up steam, neoclassical ideals of theatre became popular because of their demands for verisimilitude and moral lessons onstage. However, these ideals dismissed elements of fantastic commentary, such as choruses and soliloquies, which were perceived as too distant from reality to be acceptable. It was in France under the rule of Louis XIV that these rules were most strictly observed. There were still a few examples of the fantastic that made it to the stage, including Pierre Corneille's lesser-known tragedies Médée and Circé, which popularized warlocks and witches within the strict constructs of French tragedy. However, French academics only allowed works that reinforced their standards of plausible, theatrical action to be performed. One example of this reinforcement is the mauling of Hippolyte by a monster in Racine’s Phèdre, which was only allowed by the government at the time to take place offstage.

With the scientific method being accepted as the chief mode of understanding the natural world in the ensuing centuries, theatrical movements like Realism and Naturalism became the ideals of great drama. These movements placed themselves as the firm enemies of magic and illusion, with theatrical conjuring being driven to the borderlands of respectability. While Stage Magic became immensely popular as its own form of entertainment in the late nineteenth century, it was still culturally ghettoized in theatres specifically designated for prestidigitation, such as Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin’s Parisian magic theatre, or J. N. Maskelyne’s famous Egyptian Hall. While these stage magicians formed a genre of performance in their own right, the theatrical elements and subject matters they developed were banished from serious narrative storytelling, where they remain, at least on stage, to this day.

Since the dawn of the twentieth century, our primary targets of Fantasy in theatre tend to be children. Some of our most endearing classics, such as the Wizard of Oz and Peter Pan, first appeared in the twentieth century onstage, and while their traditions continue with big budget productions like the National Theatre’s adaptations of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, or the eagerly anticipated Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, set to make its stage debut next year, one wonders, in the post-Tolkien era, where is the adult Fantasy for the stage? Who will take up the mantle, passed from MacDonald to Moorcock to Martin? It seems, in the darkened houses of the Western World, under siege from an onslaught of realism, we’re still awaiting our Knight in Shining Armor.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here