Slovakia Program: Puppetry and Play

Slovakia has a long and rich history of puppet theatre, but today the art form is often seen as simple and uncomplicated children’s fare. Under the new artistic direction of Katarína Aulitsová, the sixty-two year old Bratislava Puppet Theatre seeks to challenge their audiences’ expectations with serious content like divorce and bullying, as well as with innovative artistry by some of Slovakia’s most innovative independent directors. Stories of Walls, inspired by Michael Reynold’s anthology of the same name and directed by Aulitsová, addresses anxiety, isolation, imprisonment, and walls, both literal and figurative.

The five stories varied from the playful—a border guard’s dog who enjoys his job (though his master doesn’t)—to the dark—a man so afraid he builds a series of walls that progressively become so enclosed he winds up in a coffin where he suffocates. Production and puppet designer Markéta Plachá’s spare and stark aesthetic highlighted the melancholy and alienation of the pieces. Each story generally included only one puppet and this puppet often portrayed the story’s marginalized and isolated figure. Watching this tiny marionette surrounded by adult humans emphasized its vulnerability and fragility, inspiring in me an urge to protect it—though not with walls but with an embrace.

The Andrej Bagar Theatre examined power, corruption, and abdication of responsibility with Joseph’s Heller’s adaptation of his novel Catch-22, directed by Ján Luterán, a young artist whose study with Anne Bogart was evident in his work. Games and play drove the spirit of the production; chess pieces hung from the ceiling, guns were colorful plastic tubes, and the ensemble projected a frenetic, childlike energy. Non-ensemble member Daniel Ratimorský played it straight as the protagonist, Yossarian, though the way he addressed the audience from a mic stand, like a stand-up comedian, further emphasized the sense of play and performance. The depiction of Colonel Cathcart as fatuous and immature was unique to this production, as it was inspired by Slovakia’s speaker of national parliament, Andrej Danko. Staged in the round in the Bagar’s studio space, the production unfolded in front of us, around us, and above us, which added to Yossarian’s, and the audience’s, sense of claustrophobia.

Theatre in Slovakia, as well as the country itself, seems at a crossroads.

Slovakia Program: One-Person Plays and Collage

Renowned Slovak director Ratislav Ballek was represented with two productions, both of which offered innovative and iconoclastic takes on classical texts. Ballek adapted and directed Bible, a reading of select stories from the Old and New Testaments, presented by Bratislava’s Aréna Theatre. Accompanied by the Slovak Chamber Orchestra, actor and visual artist Juraj Kukura read excerpts that included Genesis, Exodus, the crucifixion, and others. Throughout the performance, Kukura threw paint against a canvas, getting as much if not more on his pristine white suit. His empathetic and passionate readings highlighted the sacrifice, heartbreak, and humor in these stories, making the Bible feel fundamentally human. However, by grounding this text in human frailty, the production risks profaning the Bible for its religious audience members, some of whom expressed their disagreement at the post-show discussion.

Prešov National Theatre, an independent company founded by Rázusová with playwright and dramaturg Michaela Zakutanská in 2013, made its festival debut with Moral Insanity, adapted and performed by Peter Brajerčik and directed by Rázusová. (The piece was selected by the Be SpectACTive Audience Program Board, so it was not actually considered part of the Slovak program.) Based on the novel Prague Cemetery by Umberto Eco, Moral Insanity addresses Slovakia’s belief in conspiracy theories, as well as the rising tide of anti-Semitism and xenophobia in Europe. In a cabbage field a young man stands in a crucifixion stance, spouts racist vitriol, and insinuates that he has done even greater damage to others. A charming and appealing actor, Brajerčik slams audiences with enraging and chilling questions and statements like, “Where has it been written that you must tell the truth? And what is truth?” and “Identification with race is not merely a physical one but a spiritual one.” The play depicts the terror of these voices being amplified both in Europe and the United States.

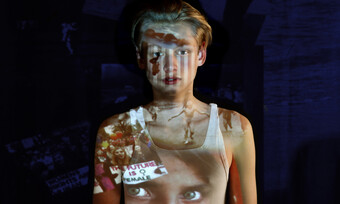

Finally, the piece that most embodied freedom as a theatrical form was Honey and Dust’s eu.genus. Honey and Dust is an artistic collective that blends theatre, fine art, dance, and music. Its projects are generally the brainchildren of director and musician Andrej Kalinka, who brings together an assortment of interdisciplinary artists to create them, often having them work outside of their fields (i.e. actors may dance, dancers may sing). “I have no borders,” Kalinka tells me. Another pillar of Honey and Dust’s work is process; the work is always evolving and changing, even in front of a live audience. This is fitting for eu.genus, a piece about family, genetics, history, and the process of becoming human. As the artists create work—be it music, dance, or sculpture— in front of the audience, they relate it to their own family histories. The audience, sitting on the stage of the Great Hall of the Andrej Bagar Theatre, which is now a live atelier, is invited to enter the playing space and explore the art before and after the performance. Though there is no linear narrative to the text, there is a clear structure and series of cumulative events. It is a story told in bodies and relationships. The collage-like nature of these events and actions happening simultaneously at times encourages the audience to choose where they focus. “You as audience are choosing this dramaturgy,” says dramaturg and dancer Milan Kozánek.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here