Theatre History Podcast #56

How to Succeed in (Early Modern Show) Business: Dr. David Nicol’s Philip Henslowe Blog

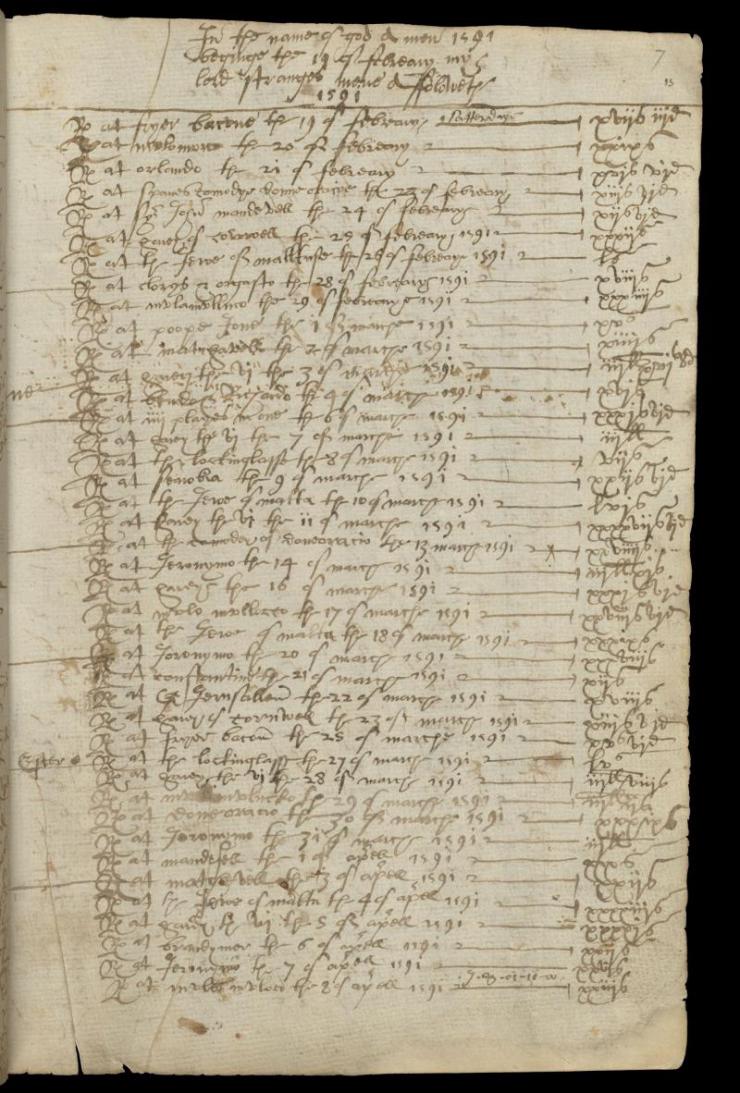

What was the business of theatre like in Shakespeare’s time? We don’t have many records, but one fascinating document has survived: a book of accounts and memoranda (often inaccurately referred to as a diary) from Philip Henslowe, a businessman in 1590s London. Henslowe helped build the Rose Theatre, where a number of plays by Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and their contemporaries received their premieres.

Now Dr. David Nicol of Dalhousie University is bringing Henslowe’s day-by-day account of early modern show business into the twenty-first century. Dave’s site, “Henslowe’s Diary … as a Blog!” follows the entries in Henslowe’s book day by day, introducing readers to plays ranging from the familiar to the forgotten, as well as trying to make sense of how financially successful each performance was. Dave joined us to talk about Henslowe’s book, the business of running a theatre in early modern England, and how he decided to turn this valuable document into a blog.

Links:

- Check out Dave’s blog and follow its Twitter account for updates.

- Explore Philip Henslowe’s book, as well as other documents from the Henslowe-Alleyn Papers at Dulwich College, through the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project.

- Examine the portion of Henslowe’s accounts that list the debut performances of Titus Andronicus and Henry VI, Part 1, via the Folger Shakespeare Library’s “Shakespeare Documented” project.

- Find out more about the mysterious “lost plays” mentioned in Henslowe’s book at the Lost Plays Database.

- To see a virtual model of what the Rose Theatre might have looked like, visit this recreation.

- Visit the Rose Playhouse’s website to find out more about the archaeological remains of the Rose, as well as how it’s being preserved today. The Rose Playhouse also hosts performances.

- You can see a similar project – one that inspired Dave’s blog – at The Diary of Samuel Pepys, a blog that posts daily entries from the diary of frequent Restoration-era theatregoer Samuel Pepys.

Additional Reading:

- W.W. Greg’s edition of Henslowe’s book is freely available through Internet Archive.

- Reginald Foakes’s edition of Henslowe’s documents.

- Lord Strange’s Men and Their Plays, by Lawrence Manley and Sally-Beth Maclean, gives additional detail on the first troupe to occupy the Rose, as well as what they performed.

- Volumes III and IV of Martin Wiggins and Catherine Richardson’s British Drama 1533-2642: A Catalogue cover the period of Henslowe’s accounts that Dave has blogged about so far.

You can subscribe to this series via Apple iTunes, Google Play Music, or RSS Feed or just click on the link below to listen:

Transcript:

Michael Lueger: The Theatre History Podcast is supported by HowlRound, a knowledge commons by and for the theatre community. It's available on iTunes and HowlRound.com.

Hi and welcome to the Theatre History Podcast. I'm Mike Lueger. What if one of William Shakespeare's theatrical coworkers had kept a blog? Obviously, they didn't have the technology in early modern England, but we do have something that's almost as good, a book of accounts and memoranda kept by businessman Philip Henslowe, who owned the theatre where many of the most significant plays of Shakespeare's time premiered.

Henslowe's record of the daily workings of his theatre have been a valuable resource to generations of scholars. Now, one of those scholars has brought Henslowe's book into the twenty-first century by turning it into a blog and associated Twitter account. Our guest this week is Dr. David Nicol, who's an associate professor of theatre studies in the Fountain School of Performing Arts at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia. In addition to working on the blog, he's the author of Middleton and Rowley: Forms of Collaboration in the Jacobean Playhouse.

Dave, thank you so much for joining us.

David Nicol: Thank you. I'm very excited to be here.

Michael: Let's start by talking about Philip Henslowe. Who was he and why was he keeping this book?

David: Okay, so Philip Henslowe was a businessman. He had a long and busy life but he's best known for what he got up to in London during the 1580s and 1590s. So this was an amazing time in the history of English drama. It was the time when a group of playwrights and actors, including William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and lesser known figures like Robert Greene were creating a new kind of drama that combined popular storytelling with poetic brilliance and they were writing plays that are still being performed today.

What these artists were centered on was something that was a relatively new idea in England at the time, and that's the idea of performing in permanent theatres in London, rather than simply traveling around the country in nomadic fashion, from town to town.

So, Philip Henslowe was a businessman who saw an opportunity to make money by building a theatre on London's South Bank, which he called the Rose Playhouse and he completed in 1587. And so Henslowe was essentially the landlord of this theatre. He was renting it out to companies of actors who would make it their permanent base for years at a time. And so, that's who Philip Henslowe was. If you've ever seen the film Shakespeare in Love, you can see Geoffrey Rush playing Henslowe as a rather bumbling, disheveled figure and I suspect the real Henslowe was the exact opposite of that.

Henslowe wasn't unique. There were lots of other theatre owners in Elizabethan London just like him, but what makes him special to us is that we know a lot more about his work than we do about the others, due to the survival of thousands of his papers. And so, using those documents to reconstruct Henslowe's life helps us to understand how the Elizabethan theatre worked.

So, Henslowe's papers survived because they were preserved by his colleague, the actor Edward Alleyn, who founded a school in 1619 and stored the documents in its archive. This school is called Dulwich College and it still exists today and the Henslowe papers are still there 400 years later. They've become known as Henslowe's diary, but it's not really a diary. It's actually an enormous collection of documents related to his business dealings and it includes lots of letters and inventories and accounts and things like that.

But one of the most important things in it is a series of lists of box office takings from the Rose Playhouse from 1592 to 1597. And in these lists, Henslowe notes which plays were performed on which day and how much money each performance made, which doesn't sound very exciting, but these are actually incredibly valuable insights into the theatrical world of Shakespeare's time and nothing else like them survives for any other theatre in Renaissance London. And so that's why Philip Henslowe is an important figure for theatre historians today.

Michael: So what does this set of documents tell us about the Rose theatre? I mean, what could you go see at that theatre and who would be performing there?

David: Okay. So, if you go down to the South Bank of London today and find the famous reconstruction of Shakespeare's Globe theatre which now stands there ... If you're there, look out for a little side street called Park Street, because if you walk a few blocks up from there, you'll find a huge office building with a weird little door opening off the street and if that little door is open, you can go inside and in there, you'll find a little museum, which displays the foundations of the Rose Playhouse, which have miraculously survived over 400 years. And you can, therefore, see the place where Henslowe worked and where some of Shakespeare's earliest plays were performed.

So that was the Rose Theatre. Henslowe built it in 1587 and expanded it in 1592 and it was the first theatre to be built in Bankside, a region on the south bank of the Thames. So, if you've ever seen a photograph of the new reconstruction of Shakespeare's Globe, you'll understand the basics of what the Rose was like. It was the same kind of theatre, but smaller. It was an octagonal building with galleries for seated audience members, which encircled a yard in which other audience members could stand up to watch the play by paying less money to do so.

There was a thrust stage jutting out into the standing area, with pillars holding a roof over it. The back wall of the stage included two doors and a little discovery space for revealing things, and also a balcony for doing balcony scenes. There wasn't a roof over the yard, so this was basically a semi-open air theatre. And again, I mentioned the film Shakespeare in Love earlier, that film does include a recreation of the Rose theatre, which in terms of historic accuracy, I would describe as not bad for a silly movie, and will give you an idea of what it might have looked like.

So, as for the people who performed there, as I mentioned earlier, Henslowe rented the Rose to playing companies, that is companies of actors who would typically make the theatre their base for years at a time. In the first two years that I covered in my blog, the Rose was occupied by a company called Lord Strange's Men and just to explain the name, all playing companies had a wealthy patron after whom they were named and they called themselves his or her men. That is, their servants. So this company's patron was Fernidando Stanley, who had acquired the title of Lord Strange, which simply derives from the surname Lestrange. It's an anglicization of that.

So anyway, that's who was acting at the Rose in 1592. They may well have been considered the best company in London by this point. They had recently acquired Edward Alleyn, who was one of the great stars of the theatre at that time, and they also had the great comic actor Will Kemp, who would later become famous by going on to work with Shakespeare and would create roles such as Bottom in A Midsummer Night's Dream and Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing. So this was a very talented group of people.

At the moment, my blog is in January 1594, this is when Strange's men have broken up and have been replaced by a different company called Sussex' Men, but they are a lot more mysterious and complicated, so I won't go into them right now.

But as for what these companies were staging, in the records I've blogged about so far, there have already been some very famous plays, some of which are still performed today. There have been two plays by Shakespeare, so there's the gruesome tragedy Titus Andronicus. There's the early history play, Henry VI, Part 1. There's also The Spanish Tragedy by Thomas Kyd, one of the great pioneering works of English Renaissance tragedy and a major influence on Hamlet. And there's been two plays by Christopher Marlowe, The Jew of Malta and the rather more obscure Massacre at Paris.

But what interests me the most is how many of the plays performed there are not famous today, even though they seem to have been just as popular in their own time. There's a play called Muly Molucco, which may be the same thing as a play called The Battle of Alcazar that survives today. There's The Spanish Comedy, the prequel to The Spanish Tragedy. There's a play about a northern folklore hero called George a Greene: The Pinner of Wakefield. And these are plays which are not normally staged today and most people have never heard of them and when you read them, it's often quite easy to see why but they were staged just as often as Shakespeare and Marlowe and every theatregoer would have known about those plays.

And even more intriguing is a huge number of plays whose texts have not survived and these are the lost plays of Elizabethan London, which we mostly know about only from their titles, and they make up the majority of the plays that were staged. So there was a play about Pope Joan. There's a play about Sir John Mandeville, The Fantastical Traveler. There's a play about King Lud, the mythical king after whom London is named. There's a play about the Roman siege of Jerusalem. There's a play about Guy of Warwick fighting giants. We can only speculate about these plays and create hypothetical reconstructions of what they might have been like. But they were once alive on the stage of the Rose. And in some ways, the lost plays are my favorite ones to think about because they get the imagination racing.

So, yeah, Henslowe's diary gives a more realistic impression of what people were actually seeing than our rather Shakespeare-centric modern descriptions of the Elizabethan theatre do. So, that's what I like about the diary is it inspires you to take a look at some of these forgotten plays and, through them, to understand better the theatrical world that Shakespeare was living and breathing in his day.

Michael: Now when you were talking about some of the various theatre troupes that played at the Rose, this name keeps coming up, Edward Alleyn. What did he have to do with Philip Henslowe? Why was he so closely associated with him?

David: Yeah, Edward Alleyn was very closely bound up with Henslowe. During the time that my blog covers, the 1590s, Alleyn was performing at the Rose with various different companies and he must have been one of the major reasons for people to visit that theatre. He seems to have been a very tall man with a very loud voice and he specialized in larger than life heroes and villains. So his most famous roles include the unconquerable conqueror, Tamburlaine, the crazed necromancer, Dr. Faustus in Christopher Marlowe's plays of those names. He also most likely played the vengeful father, Hieronimo, in The Spanish Tragedy, the mad warrior, Orlando, in Orlando Furioso, the evil Muly Mahamet in The Battle of Alcazar, and the deliciously vengeful Barabas in The Jew of Malta, all of which became iconic figures in London culture. And Alleyn's roles were still being referenced in poems and plays and prose for decades afterwards.

So he was a major, major star at the time. But he wasn't just a great actor. He was also a very canny businessman as well and he seems to have formed a very close relationship with Philip Henslowe. He was collaborating with him on various business ventures, like the management of the Rose and other theatres. He was also very tied up with Henslowe in bear baiting, as well, which is a major part of their work. He was also close to Henslowe on a familial level, as well, because he married Henslowe's stepdaughter. And so, their lives became intertwined and that's why Henslowe's diary ended up in the archives of the school that Alleyn founded and so it's partly due to Edward Alleyn that we get to read this stuff today.

Michael: Now you mentioned a moment ago something called bear baiting. What was that?

David: Bear baiting is a deeply unpleasant form of entertainment in Elizabethan London, in which one ties a bear to a stake and lets a large number of dogs attack it. And the viewers laid bets on how many dogs the bear will kill. That's essentially bear baiting. Great fun. Not very pleasant at all. But as far as we can tell from the records, it was quite a major part of the work of Henslowe and Alleyn and one of their major sources of income, so I guess we just have to live with the fact that the people who create great art are also evil scumbags on a certain level.

Michael: And on that note, I guess I'd be curious, looking at Henslowe's book, what does it teach you about the business of theatre? About the business of entertainment in early modern England?

David: Okay, to answer that question, I'd like to give you a sense of the documents that I'm working from, that is the list of performances and their box office takings, which are the fulcrum of this blog that I'm working on. So, I'm just going to read out a small part of what these documents sound like. This won't be exciting, but it will give you a sense of what they're like. So this is just a small section.

"Received at The Fair Maid of Italy, 12 of January, 1594, nine shillings. Received at Friar Francis, 14 of January, thirty-six shillings. Received at George a Greene, 15 of January, twenty shillings. Received at Richard the Confessor, 16 of January, eleven shillings. Received at Abraham and Lot, 17 of January, thirty shillings. Received at King Lud, 18 of January, twenty-two shillings. Received at Friar Francis, 21 of January, thirty shillings. Received at The Fair Maid of Italy, 22 of January, twenty-two shillings. Received at George a Green, 23 of January, twenty-five shillings. New, received at Titus Andronicus, 23 of January, three pounds and eight shillings."

So, that wasn't very exciting, but you might have noticed that a different play is performed every day. You might have noticed that some titles kept returning while others you only heard once, and the last one was described as new. So, to understand what you heard there, you have to understand that Elizabethan actors lived very differently from modern theatre actors. They worked via a system known as the repertory system, which meant that their company would perform a different play each day. Now, in modern theatre we don't do this. Modern theatre companies plan out their seasons far in advance and perhaps perform the same play every night for weeks on end, or if they're a big company, they might have two or three plays being performed on rotation for that time. But they certainly don't live the way that Elizabethan companies did. Each company owned around twenty or thirty plays and the idea was that they performed a different one each day, gradually cycling through the plays they owned, sometimes adding new ones, sometimes dropping old ones that had gone out of fashion. They didn't plan far in advance, which meant that the actors were expected to memorize their roles for all the plays in the repertory and to be able to perform them with only a few days' notice.

So this sounds like a really crazy way to run things, but there is a logic behind it. There is a logic of variety and of flexibility. These companies are operating in an age when theatre is the most popular form of entertainment in London and there's a huge demand for plays from the members of the theatre-going public, many of whom loved to go to the theatre many times a week and a company would not survive if it just performed the same play for weeks or even days at a time. The audience would get bored by the repetition and would just start looking elsewhere. So instead, the companies needed to attract audiences by offering the chance to come back again tomorrow and see a totally different play.

They also needed to have a good sense of which plays were popular crowd-pleasers, which were not and which had once been popular but weren't anymore. So, to adapt to this knowledge, they needed the ability to make decisions on the fly. If a play was no longer drawing big audiences, they needed to perform it less often. If a play was scoring huge audiences, they needed to program in new performances. And so, within this system, the companies were able to change their minds at the last minute.

There's a lovely example of this, a story about this, from 1612, which is recorded by the Venetian ambassador to London, who went to visit one of the theatres in London and he writes at the end of the show, the actors came onto the stage and announced the play that they were going to perform the next day. But the audience booed and instead shouted, "Friars! Friars!" which seems to be referring to an old play called Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, which is about two comedy friars. The actors, hearing the audience shouting this, backed down and agreed to play the friars tomorrow instead of what they were planning to perform. So, clearly, flexibility was very paramount in this system and you needed to be able to placate an angry audience if you had suggested the wrong thing.

If you needed to run a company this way, you needed actors with amazing memories and very quick wits. Actors normally studied and learned their lines alone or in pairs and received only one group rehearsal before the play was performed and so typically they're living in this system in which they wake up in the morning, having already memorized their parts. They get together at the theatre for a group rehearsal. In the afternoon, they perform the play to a paying audience and then any remaining free time is presumably devoted to frantically learning and practicing their parts. It seems like a really incredibly stressful and exhausting lifestyle. And because the potential for onstage mistakes was enormous, but obviously, there are advantages as well.

Because if you think about the incredible levels of focus that these actors must have had to be successful in their work, you can see how exciting their performances may have been both for the audience and for each other. Because these actors had to be listening intently to their fellow actors and adapting quickly to cover any mistakes or unexpected audience reactions. So they couldn't be lazy ever. They couldn't ever be stale. The actors always needed to be on the ball at all times. And so, I feel like their performances probably had this crackling energy to them that is really hard to understand or really reproduce, even, today.

That was explaining the system in which these actors are working. To go back to Henslowe's diary, now, that's what we're looking at when I was reading out that list there. It's a list of each day's performances at the Rose theatre and each day, Henslowe records the title of the play performed at the Rose and the box office takings. He's not interested in their artistic quality. He doesn't care who wrote them. He doesn't care what they're about. All he cares about is was there a big audience or not. He's a simple man in that respect.

In terms of what constituted good box office or bad box office, before I answer that, I have to make it clear that Henslowe's diary is a very mysterious and confusing document and there is much about it that we don't understand. What I can tell you is that the highest box office recorded so far has been for a production of Henry VI, with seventy-five shillings. The lowest one was a lost play called [inaudible 00:17:24] of Bordeaux, which got five shillings. So that's the difference we're looking at here. Seventy-five shillings versus five shillings. The average for most productions is around about thirty-three shillings.

Doing the math about what this actually means is really complicated and I do include a full description of what we do and don't know on my blog. But just to give you the gist, a play that takes sixty to seventy shillings is probably pulling in something like 2,500 people. So it's a pretty huge audience. But those days are really rare. The average is more like thirty-three shillings, which indicates something around about 1,000 or so people in the theatre. And so it suggests that on most days, the theatre is only half full.

There are various complications to all of this and perhaps the most interesting complication involves the days when the box office was highest, because the surprising thing is that what raised the most money was always debut performances of new plays. That's what always seems to get the highest box office. Brand new plays are the most popular. And this might seem a bit weird, but the reason seems to be that Elizabethan audiences loved novelty and the introduction of a new play was an exciting event which would draw mass audiences.

That said, there is another explanation which may be that the players are actually charging higher entrance fees for debut performances. There is some evidence that the entrance fee may have been doubled when a new play was being performed. So it's possible that the premiere audiences may not be as big as they seem. But then again, it does seem that there's lots of historical evidence at the time that audiences did tend to flock to the theatre to see new plays and were happy to pay extra. So it's very complicated, but it does seem that newness was an important part of the process of success in this period.

One of the things that we learn out of all of this is the question of which plays were popular and which were more popular than others and what kind of plays were more popular than others. One way of assessing popularity is to look at which plays were performed the most frequently. So, if you look at the part of the diary that's about Lord Strange's Men, the most performed play was Henry VI, which is almost certainly the play that we now call Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 1. And this was staged like fifteen times in four months and was performed pretty much on a weekly basis. There were other plays which were performed with a similar level of frequency and they include The Spanish Tragedy, the play of Muly Molucco, which may be called The Battle of Alcazar now, and The Jew of Malta by Christopher Marlowe and those plays were the bastions on Lord Strange's Men, although they didn't always do that well at the box office, they could reliably pull in enough of an audience to pretty much half fill the theatre.

But there was also a bunch of plays that the company only revives once a month or so and that includes The Spanish Comedy, the prequel to the Spanish Tragedy. It includes the play of Sir John Mandeville. It includes weird plays what we don't know much about called Bindo and Ricciardo and Machiavel. And I find the existence of these monthly performances really puzzling. I feel like it must have been a lot of mental effort for the actors to return to plays that they didn't perform for weeks at a time. And most of these monthly plays didn't receive noticeably bigger or smaller audiences than the other ones and so I don't quite understand why some of these plays are relegated to monthly performances and some are done once a week. It's very strange.

And then you also see plays that the company gave up on. So you see them performing a play called Brandimer and a play called Jerusalem. You see them perform those plays only twice. A lot of these plays may have been old ones that the company was trying to revive but then decided they weren't worth reviving again. And there were also weird things, like there's an enigmatic play called The Tanner of Denmark, which has this amazingly successful premiere, one of the most successful of the Rose, but then never gets staged ever again. There are a lot of mysteries going on there and you can't understand what's going on in the heads of these people.

One of the other things you find is if you take all of the complications into account, I think probably the most impressive play of the period was probably Christopher Marlowe's Jew of Malta. It wasn't performed as often as some of the other plays and it never achieved the enormous heights that some of them occasionally achieved. But it did always achieve box office that was consistently above the average. And so, I think The Jew of Malta, by Marlowe, is the most consistently popular play of those days and I think the actors probably looked forward to performing it. I imagine them walking on stage being very certain that they could be looking at a huge, happy audience, no matter when they were performing The Jew of Malta. With almost all the other plays, they never quite knew what they were going to get.

So, these are some of the things that you can find out about the workings of the theatre industry by looking at what seems like a rather simple and unexciting list of plays.

Michael: Yeah and I'm curious in hearing this what your sense overall of Henslowe and I guess his business partner, Ed Alleyn, what's your sense of them as businessmen? How successful were they? If they were successful, why was that the case?

David: This is really difficult a question to answer because it's so hard to compare them with the other theatre managers of the time. We don't have the records for those matters, so it's hard to say whether Henslowe was an averagely successful businessman of his day or whether he was one of the greatest successes of his day. It's really hard to tell. One of the things I don't understand about Henslowe from looking at the diary is how much control he has over the plays that are being chosen by the actors. I'm not sure why he's writing this stuff down. I'm not sure whether he's literally taking these records that I've described and going to the actors and showing them the data and saying, "Could you please stop performing Harry of Cornwall? Nobody likes that play." I don't know if that's what's going on or if he's just writing down the names out of interest and is letting them make their own decisions.

One thing I did learn by doing this project is I learned a few rules of the Rose theatre and Henslowe, perhaps, was involved in developing those rules. One rule seems to be that performances of a play need to be spaced out to avoid overkill. So the company hardly ever performs the same play in one week and when they do, it seems to draw a smaller audience. And this seems to be related to another rule which is absence makes the hearts grow fonder. I found several instances in which the company seems to be holding off on performing a play for a couple of weeks and then when they bring it back, it achieves a much higher box office than it normally does, as if this causes the audience to miss it and become desperate to see it.

And the rule that made me the most happy was make sure you perform during the holiday period, because during the holidays, Londoners will flock to the theatre. It's really nice to imagine the excitement of actors and audiences on days like May Day and the week of Whitsuntide and the Christmas season. You can see there in the records that people have days off then and they were spending those days off at the theatre. And equally fascinating for me is actually the really dismal box office that they get during Holy Week, which clearly is when Londoners feel guilty about going to see plays. And then in Easter week, the following week, you see suddenly the box office suddenly boosts up into the sky because the Londoners are clearly in a really festive mood and they're just like, oh, thank goodness we're no longer being holy. Now it's all about pies and theatre.

So, yeah. I can't be sure if Henslowe was unusually successful, but I do feel like I've identified some of the rules of success in his playhouse and he seems to have been following them.

Michael: Now can you let us in a little bit about the nuts and bolts of running this blog? Why did you start it? How does it work?

David: Yeah. I've always wanted to do a blog based on an existing historical diary. This is something I've always enjoyed reading and there are other examples of them on the internet. The classic example is pepysdiary.com, which was begun by a chap called Phil Gyford, who started it in 2003. Samuel Pepys was the seventeenth century civil servant who kept a diary from 1660 to 1669 and this wonderful text gives us an amazing glimpse into the minutiae of everyday life in the past and features Pepys' descriptions of his erotic escapades with various ladies, but also his problems with home reno and his eyewitness account of the Great Fire of London and so it's a really fascinating document. And Gyford was posting one entry a day from Pepys' diary from 2003 to 2012 and he attracted a very large readership who really enjoyed the opportunity to read this very lengthy and intimidating text in bite-sized chunks. And so Gyford did finish that project and he posted the entire ten year diary and you can see it online right now.

There's lots of other examples of this sort of thing. There's somebody who posted Captain Cook's log book as a blog so that you can follow Captain Cook on his journey of discovery around the Pacific in the 1770s. And I like this kind of thing and I was trying to figure out why I like this kind of thing, because it's really nerdy. And I was like, why do I like this really nerdy stuff? I think it's the bite sized nature of it is appealing. It makes long and complicated texts more digestible. But what I also like about it is the sense of duration because a blog in which you can't simply read the diary straight through, but have to wait for the next installment each day means that you get a sense of time passing realistically and you get a sense of how long things actually took and I found my favorite bits of these blogs were the boring ones where nothing interesting was happening.

The Captain Cook blog was a great example. It contains amazing stuff like the circumnavigation of New Zealand and the first ever description of a kangaroo and the observation of the transit of Venus and a shipwreck and things like that. But 75 percent of the diary is just like, "Calm. Light drizzle in the afternoon. Winds southeasterly. Shot a seagull." That sort of thing. And the books about Cook's voyages ignore all of this or they condense it into a couple of sentences, but when you read it in the ... When you read it in the printed diary, you tend to just skim read this kind of stuff. But when it's presented on a blog, watching literally hundreds of these entries unfold day by day as Cook makes his crossing of the vast Pacific from Cape Horn to Tahiti, it gets this amazing sense of the passage of time and of the epic nature of his voyage and it reminds you that every single entry represents an entire day, sun up to sun down, sailors scrubbing the decks and manning the halyards and squinting into the distance and arguing and singing shanties and things like that.

So, experiencing this day by day is like having this other world going on in the background while you live your own life. So that was why I find these things rather beautiful and I had always wanted to do one of these myself, but I wanted to do something a bit more extensive than just posting the primary sources because the problem with just cutting and pasting historical diaries into a blog is that a lot of them require really specialist knowledge to be understood, whether it's Samuel Pepys and his London gossip or Captain Cook and his nautical jargon, a lot of these blogs are not as interesting as they could be to the general reader because they're so arcane.

And so, when I set to creating my own one, I wanted to be able to frame the diary entries with my own writing in order to introduce them and to paraphrase them and to contextualize them for the general reader. So, I don't know about much, but I do know a bit about Renaissance drama, so looking at Henslowe's diary, I realized that it was actually ideally suited to a blogger, because although it does cover five years in total, there are actually large chunks of it that are missing and that gives the blogger lots of breathing space and chances to catch up.

So for example, the first block covers February to June, 1592, so I decided to start posting its entries from February to June of 2016, posting each entry on the same day that they were written, except 424 years later. But luckily, there were large breaks after that, which gave me a time to catch my breath and catch up and regain my enthusiasm and then carry on once the diary entries restart a few months later.

The reason I did need to take a break is because you can't just post the diary entries. Most of them are incomprehensible. The figures don't mean anything to the outsider, so instead of simply presenting the entries bare, I wrote little essays for each one, explaining about the play in question and I tried to do it in a fun way, not a [inaudible 00:29:02]-faced scholarly way, while still being accurate. Because of the lengthy breaks, I'm able to write these entries far, far in advance and then just program them to publish automatically, so that helps a great deal.

To publicize the blog, I've created a Twitter feed as well, in which I essentially summarize the essence of each day's post and then give a link to entice people to read the entire thing. So, yeah, the way the blog works is that if you read it, due to the nature of the diary, you are initially introduced to a different play each day and you learn about the different play each day, but after a while, you start to see plays being repeated and so my blog entries become a lot shorter, correspondingly.

Some plays get repeated a lot, because they're popular. Others appear less often and gradually fade away and then get replaced by new ones. And so, the reader experiences, over time, how plays rose and fell and sometimes rose again in popularity and they get a sense of how it feels to be an actor or a keen playgoer in this age. So that's the essence of how the blog works.

Michael: You know you were just talking a moment ago about getting a sense of what it feels like to be an actor, to be a manager, to be someone who goes to the theatre a lot. I'm wondering, what have you learned from doing this project?

David: I think the overriding impression I got from doing this was a much greater appreciation of the industry and the dedication of the Elizabethan actors. I noticed that after the first three weeks of posting the blog entries, I realized that the actors had just performed fifteen different plays over eighteen days, which is just insane. Their memory skills and their focus and their work ethic must have been phenomenal. It must have been a really amazing lifestyle and on one level, as an actor, you sort of imagine that this must be the greatest lifestyle ever, but it must have been also this completely, all-encompassing one which would completely suck up your life. I can't believe any of them managed to find time to eat, let alone get married and propagate children, which some of them did.

So, we're really lucky that Henslowe's diary survives. It's the one document left that really preserves on paper the achievements of these long-dead actors and so, I hope that turning them into a blog does some justice to them. It sort of reproduces the patterns of their lives and allows us to imagine them existing, as I said, in a parallel universe alongside us.

Yeah, so I think what it does is it ... I think it makes the case for the historical diary blog as a valuable way to look at old plays and to capture some of the missing details of real life, which sometimes escape us.

Michael: Now, for listeners who might be hearing you talk about Philip Henslowe and his world and might want to learn a little bit more, what resources would you recommend, beyond the blog, to go check out?

David: First of all, if you want to see Henslowe's diary, you should go and look at the Henslowe Alleyn Digitization Project online, which is a beautiful facsimile of the entire thing and it gives you a sense of what this amazing document actually looks like. That said, it is not particularly exciting for non-experts because it's all in very, very difficult Elizabethan handwriting and mostly just looks like a lot of scribbling to the uninformed.

So if you actually want to read Henslowe's diary, I've been using W. W. Greg's transcript from about 1910, I think, which is out of copyright and available on archive.org. If you want a more up to date scholarship, you need look out for Reginald Foake's edition of the diary, which you could find in your local academic library, I would imagine.

I should probably say before I go on, that I want ... I should probably stress that unlike a lot of contributors to your podcast, I'm not claiming to be offering any groundbreaking scholarship here. I'm not providing anything new in terms of scholarship. I'm synthesizing the work of people who are much better at this than I am and many amazing scholars have read and studied and elucidated Henslowe's diary and I'm totally indebted to their labors. All I'm doing here is trying to synthesize this and communicate this interesting material to the general reader.

But for those who wish to go on and look at the texts that I am completely indebted to, there's been a number of theatre historians have studied the repertories of individual playing companies, and in particular the book Lord Strange's Men and Their Plays by Lawrence Manley and Sally-Beth MacLean was absolutely invaluable to my work.

But the biggest aid of all was two encyclopedic projects that help with the task of writing about plays, especially plays that don't exist anymore. So first of all, Martin Wiggins' amazing Catalog of British Drama, which is being published in print in a series of volumes at the moment and is up to volume eight at the moment, has entries on every single play of the period, including all the lost ones, and collects together all the data that we have on them. And it's an incredibly useful resource to use on a project like this. I don't think I could have done it without the Catalog. And secondly, the online Lost Plays Database is a wiki project intended for Renaissance scholars and is attempting to collect information on all of the lost plays of the period and is a project which is open to any scholar who is interested in working on it. So if you are intrigued by these enigmatic lost plays, this is first of all an amazing resource for you to go and learn about them. You can also contribute to it yourself, if you feel inspired to do some research yourself and continue the process of building our knowledge about these enigmatic but fascinating plays of the past.

Michael: We post links that will let you explore Dave's Philip Henslowe blog as well as links to sites such as digitized copies of the Henslowe Alleyn papers. Dave, thank you so much for introducing us to your blog and for your insights into the business of theatre in Shakespeare's time.

David: Thank you, Michael. It's been an absolute pleasure talking to you.

Michael: If you'd like to continue today's conversation, please visit HowlRound.com and follow HowlRound and @TheatreHistory on Twitter and Facebook. You can also visit our website at theatrehistorypodcast.net where you can find links to all of our episodes and you can email your questions and comments about the show to [email protected].

A big thank you to the staff at HowlRound, who make this show possible. Our theme music is The Black Crook Gala, which comes to us courtesy of The New York Public Library Libretto Project and Adam Roberts. Thanks, as well, to [Tip Cress 00:35:29], who designed our logo. And finally, thank you for listening.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here