Time Sensitive

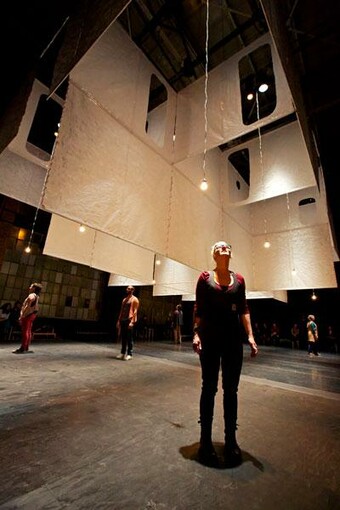

The central set piece in Ragged Wing Ensemble’s Time Sensitive is made of one of the most challenging materials to use in theater. It’s heavy. It’s messy. It’s slippery. You can touch it, but not for long. You can store it, but only at great cost, and you have to create it anew for every performance.

But ice sculptures also have much to recommend them for the theater. Ice amplifies lighting as no other substance can, creating prisms that multiply real light sources so that an entire stage seems to shimmer.

In this production, the hefty frozen blocks connected by metal chains, all designed by Carter Brooks, aren’t just aesthetic. They are islands of sanity in a sea of chaos; you might find yourself looking at them again and again, practically clinging to them in effort to ground yourself, to help keep your perspective human in scale.

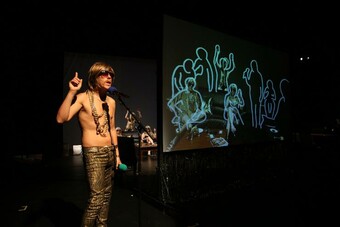

Time Sensitive, which RWE rehearsed for four months (a very long time by Bay Area standards), is the latest product of the sui generis creativity of artistic director Amy Sass. The nine-year-old company specializes in original, ensemble-created work with wildly inventive but precise physicality. It takes on unwieldy, abstract ideas and makes them dramatic through created or reinvented myth.

Time, unsurprisingly, is the unwieldy, abstract idea that the company explores in Time Sensitive. The show chronicles how time insensitive we are, how we manipulate time to meet the demands of an increasingly demanding society while our bodies, slow to evolve to help us meet those new demands, stubbornly march to their own biological beat. What, this production asks, are the stakes and consequences of those conflicting rhythms?

What, this production asks, are the stakes and consequences of those conflicting rhythms?

At rise, the characters are an undifferentiated mass, performing a highly stylized movement sequence that creates pulse-ratcheting music from the language and cadence of modern urban life. The ensemble members repeat the phrase, “next big thing,” at an uneven, accelerating and decelerating pace, heaving their bodies correspondingly so as to aurally and visually conjure a train. At another point they mime frantic typing while also marching at a slower but still crisp and menacing speed; the two juxtaposed paces suggest workers who must drain every cell in their bodies for the dubious purpose of lurching their machine—a project, a company, a system—forward.

In these scenes’ focus on the slogans, mantras, and expressions that are both a byproduct and a buttress of the business world, Time Sensitive has much in common with Machinal, Sophie Treadwell’s 1928 play about a young woman so out of sync with the job, the marriage, and the pace society allots her that she murders her husband. Both plays take the language of business out of context, delivering it a manner that seems at times in fast forward, at other times little different from how we often hear it. Both plays create music from empty jargon, exposing the poverty of our language, how it conspires to reduce us to machines. Consider these passages from the two plays. From Machinal:

JONES: Hew to the line.

ADDING CLERK: Hew to the line.

STENOGRAPHER: Then I'll hurry.

JONES: Haste makes waste.

ADDING CLERK: Waste.

STENOGRAPHER: But if you're in a hurry.

JONES: I'm never in a hurry—That's how I get ahead!

First know you're right—then go ahead.

ADDING CLERK: Ahead.

And from Time Sensitive:

ROACH Access. You gotta get in, to move.

ENSEMBLE Access

ROACH When you move, you move up. Access.

ENSEMBLE Getting in

Moving up

Going forward

Access.

ROACH Can’t get in? You won’t move a day in your life.

The two works even play with the same expressions. From Machinal:

JONES Tell Miss A. the early bird catches the worm.

TELEPHONE GIRL The early worm gets caught.

ADDING CLERK He's caught.

From Time Sensitive:

ENSEMBLE bird, bird

Bird, gets the worm.

GO!

bird, bird

I want that worm

C’mon. Say it.

bird, bird.

Want, want that worm.

Worm.

I want that worm.

It’s worth noting that 1928 has much in common with 2013. While in that year America was careening toward an economic precipice and now we have plummeted over another one, both times are characterized by very high economic inequality and by stock market indices that reflect the health of only those at the top, ignoring the roiling instability underneath. In both times, a few industries grew explosively but failed to raise the tide to bring others out of the lurch. This is a bit far-fetched, but taken together, these two plays might suggest that our sense of time is deeply tied to how we perceive our worth relative to others.

Inequality is certainly a focus of RWE’s piece. The show features one character, Bill (Philip Wharton), who lives in a skyscraper so high that, with binoculars, he can almost see the edge of his sprawling metropolis; it’s also so high that, even with state-of-the-art elevator technology, no one will take the stratospheric journey to visit him. His only companions are his binoculars, his unappetizing pink booze, and the elevator repairman (Soren Santos) assigned the daunting task of connecting him to the rest of the world. Our notions of space, RWE suggests in this scene, are just as distorted as our notions of time; space, like time, is a resource to be bent and conquered as we grow infinitely wider, taller, bigger. When Bill decides to bridge that physical gap, breathing air and touching earth for the first time in eons, a gun-toting character from society’s nether-regions, Roach (Anthony Agresti), only legitimizes Bill’s desire to segregate himself.

Another plotline focuses on a woman who, like the main character in Machinal, finds the dictates of her body are in conflict with the way her world defines time. Tilly (Annie Paladino) broaches the subject of maternity leave with her boss (DiLecia Childress), who tells her, “We offer it, but between us...you know how it is...outta sight, outta mind. Positioning is key. You don’t want to lose your edge.” It’s the future, though, and women can accelerate their pregnancy; Tilly elects to complete hers in a month, and its botching is among the most harrowing moments I’ve seen onstage. The baby pops out after only a day in the womb, and with each step it takes it ages years. In seconds it has grown up and walked away from its mother before she’s gotten a chance to talk to it or touch it. It’s a searing comment on the cold, calculating way our society talks about pregnancy: as time away from career building; as an explanatory note on a lackluster resume; as a quantifiable liability to be minimized as much as possible.

These different stories (and there are many others) show that time is in crisis. In the second half of the play, the Clockmaker (Addie Ulrey), a Father Time figure, is dying, and his assistant The Kd (Keith Cory Davis), a wind-up toy, will not brook his death, or even the idea of death. As they break rules of biological time, the pace of the play slows down and the rhythms become soupier; characters’ paths cross for the first time, and their different senses of time collide, slowly breaking down the idea of objective time. It can be difficult to tell what’s going on—characters say things like, “Without edge, there is no center. There is no Now. It will be the same time all the time and that time will never be Now. Not the Great Now. The Now of dreams and spirit. That Now will be over”—but in speed and tone it’s a welcome relief from the pace and rigor of the first act.

... our own concept of time is unsustainable, and it’s not at all the only way to organize our minds.

The overall message, though, is clear: our own concept of time is unsustainable, and it’s not at all the only way to organize our minds. Sass got much of her inspiration for the play from Jay Griffiths’ A Sideways Look at Time, which asserts that there have been as many ways to conceive of time as there have been eras and cultures. Manifested here, that idea is a subtle but stirring comfort amidst the piece’s sharp criticism.

As all this unfolds, unravels, dissolves, there remains one constant: the familiar drip drip drip of the ice sculptures on the rear wall of the stage—comforting in their familiarity and steadiness, but chilling in that you can’t help but wonder when they will all melt away.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here