Welcome to the fifth year of the Theatre in the Age of Climate Change series! In honor of spring, the season of hope, we’re keeping an eye on two promising US policy proposals: the Green New Deal, spearheaded by Congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, and the Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act, proposed by a bipartisan group of lawmakers and endorsed by Citizens’ Climate Lobby. And, to add to this well of positive energy, HowlRound is featuring some of the most hopeful work being done at the intersection of theatre and climate change. — Chantal Bilodeau

What I Learned About Gender Parity and Racial Diversity from Running a Global Participatory Initiative

A few months ago, I came across an article by science journalist Ed Yong titled “I Spent Two Years Trying to Fix the Gender Imbalance in My Stories.” Inspired by a colleague who analyzed the gender ratio of sources in her own writing, Yong did some forensics work and discovered, to his surprise, that in 2016 only 24 percent of his quoted sources were women. And 35 percent of his stories featured no female voices at all.

“I knew it wasn’t going to be 50 percent, but I didn’t think it would be that low, either,” he wrote in the piece. “I knew that I care about equality, so I deluded myself into thinking that I wasn’t part of the problem. I assumed that my passive concern would be enough. Passive concern never is.”

After reading this, I decided to do a bit of investigating of my own. Every other year, I run an initiative called Climate Change Theatre Action (CCTA). First piloted in 2015, CCTA is a worldwide series of readings and performances of short climate change plays presented to coincide with the United Nations Conference of the Parties, the meetings that bring together world leaders to discuss strategies to reduce global carbon emissions.

Fifty playwrights from around the world are commissioned to write five-minute plays about an aspect of climate change based on a prompt. This collection of plays is then freely available to producing collaborators interested in presenting an event in the fall (this year’s events are scheduled for 15 September to 21 December). Events can range from readings to fully-produced performances, from podcasts to film adaptations.

Idea Moose by Kendra Fanconi, directed by Lorca Peress and choreographed by Jennifer Chin. Acting company: Gabrielle Lee, Gus Scharr, Kathryn Layng, Avondre E.D. Beverley, Tanya Perez, Joyce Griffen, Lorca Peress, Daniel Carlton, Cary Hite, and Maya Saroya. Multistages, New York. Photo by Hunter Peress.

Our fifty playwrights are carefully chosen to represent all continents and dozens of cultures, including several Indigenous nations. So on that front, I knew we were doing well. In fact, in 2017 we had a majority of female writers—thirty-two women and eighteen men—and almost 60 percent of the group (twenty-nine people) was comprised of writers of color and Indigenous writers. The same is true for this year. For CCTA 2019, the gender ratio is exactly 50/50 and the percentage of writers of color and Indigenous writers is 60 percent (thirty people).

The real question, then, is what happens on the other end? Once the fifty plays are written, we make them available to anyone who expresses the desire to organize an event in their community. People get a link that gives them access to the plays and to a spreadsheet with the writers’ names, countries of residence/heritage, title of the plays, number of characters for each play, and keywords—for example, “comedy,” “melting ice caps,” or “water.” Equipped with this information, producing collaborators are free to choose which play(s) they want to present.

After reading Yong’s article, I enlisted the help of a friend whose math can be trusted and we crunched some numbers. Since 2015 was a pilot year, we focused on 2017. What I wanted to know was: What happens to gender parity and diversity when plays are picked by people other than artistic directors running major theatre companies? Do the same biases that favor white male playwrights manifest themselves or do things change when power is distributed and there is less money at stake?

A majority of events took place in the United States, so this is reflective of an American perspective. The exact breakdown for CCTA 2017 was 134 events presented across twenty-three countries, with ninety-one of those events taking place in sixty American cities. Together, the plays were shown a total of 747 times.

This ratio reversal suggests that contrary to what has long been a popular belief, and is still a persistent and almost always unacknowledged assumption, people are interested in women’s voices.

People Like Women’s Plays

Ten years ago, Emily Glassberg conducted a study titled “Opening the Curtain on Playwright Gender: An Integrated Economic Analysis of Discrimination in American Theater.” A series of scripts were sent to different theatres, sometimes with a female pen name, sometimes with a male pen name, to assess whether the quality of the writing would be perceived differently based on the gender of the author. As you can probably guess, the results were appalling.

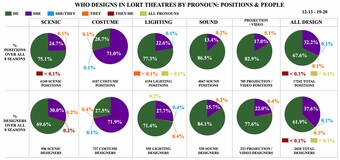

More recently, American Theatre Magazine reported that female playwrights who were produced off-Broadway in the last five seasons (2013–14 through 2017–18) represent between 28 and 41 percent of all produced playwrights. This is an improvement—from 1994 to 2001, that number hovered at 17 percent. However, we’re still far from parity. If I look at the 2018–19 season in New York City where I live, there is at least one major theatre that has programmed one lone female playwright and four (white) males.

But what happens if we take the decision-making process out of the hands of artistic directors and give it to artists? CCTA events are often curated by groups of individual artists who come together for the project or by students and faculty who put on an event at their university. As a result, the curation tends to be more democratic and, I assumed, more representative of our society. And lo and behold, when we ran the numbers, this assumption was validated: the gender ratio for the plays presented in CCTA 2017 was 42 percent male vs 58 percent female—almost a direct reversal of the American Theatre Magazine statistics.

Is it a fluke? A representation of a real difference in the expression of power? A sign that things are changing? It’s hard to tell, but this ratio reversal suggests that, contrary to what has long been a popular belief, and is still a persistent and almost always unacknowledged assumption, people are interested in women’s voices. They like women’s plays. When there’s no incentive to privilege men and uphold the status quo, when the decision-makers are more or less evenly distributed along gender lines, people are happy to read, study, and perform plays written by women just as they would plays written by men. The entrenched bias that Glassberg found a decade ago, both on the part of men and women who were reviewing the plays, did not show up in CCTA.

I took this analysis one step further and next reviewed the number of presentations that each CCTA play received: eight of the ten most-produced plays were written by women. This actually echoes American Theatre Magazine’s “Top 10 Most-Produced Plays of the 2018–2019 Season” (which is actually eleven due to a tie), where nine of the plays were written by women. Maybe real progress is on the way.

Rebecca Agbolosoo-Mensah in Gaia by Hiro Kanagawa, One World Theatre Productions, Shanghai, China. Photo by Alejandro Scott.

Diversity? Yes, Please!

Statistics about racial diversity are worse than statistics about gender. A 2015 study analyzing three years of data from productions in regional theatres in America found that nearly 90 percent of plays were written by white playwrights. In 2017, Anthony Byrnes and Christina Ramos dug through the fifty-year production history of the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles and found that out of 298 productions, 250 were written by white playwrights. No matter where we look, we’re reminded that despite an increasingly more diverse American population, racial diversity in the theatre is far from being embraced.

Again, I wanted to see whether a change in power structure and decision-making context, as exemplified by CCTA, affected what plays got programmed. Was our offering of twenty-nine plays by playwrights of color versus twenty-one plays by white playwrights enough to encourage diversity in CCTA presentations? Or was the supply side irrelevant because there’s still too much resistance to diversity on the demand side?

No matter where we look, we’re reminded that despite an increasingly more diverse American population, racial diversity in the theatre is far from being embraced.

An intriguing aspect of this question is that I don’t know whether or not diversity was a factor in the curation of events. For better or for worse, in a professional context, the ethnic background of a playwright is always a determining factor. Efforts are made to either include diversity or to exclude it, but in our current political reality, we can’t fool ourselves into thinking that the decision is ever neutral. In CCTA’s case, however, unless our producing collaborators knew or looked up the playwrights, or unless the playwrights had names that pointed to a specific culture or were based in an ethnically homogeneous country, it wasn’t immediately apparent in reading the plays who was a writer of color and who wasn’t.

Out of the 747 presentations that the CCTA plays received, 363 were of plays written by playwrights of color and 384 by white playwrights. That’s almost the same number of presentations for both groups. However, we had more playwrights of color (twenty-nine) than white playwrights (twenty-one). So when we account for this difference, it means that 41 percent of presentations were of plays by playwrights of color and 59 percent were of plays by white playwrights.

I expected the racial bias in our field to be reflected in these numbers—if not exactly then at least in great part—so I was thrilled to find out this was not the case. In fact, CCTA did better than the theatre field by a factor of four. Or, put another way, for every artistic director out in the world who programs a play by a playwright of color, CCTA collaborators present four. That’s a huge difference.

In addition, out of the ten most-presented CCTA plays, each with more than twenty presentations and some with as many as sixty, five were written by playwrights of color. (In the American Theatre Magazine top ten list, only two of the plays were written by playwrights of color.) CCTA artists and audiences embraced racial diversity when there was no outside pressure to do so, no “diversity” box to check. They chose stories that spoke to them, stories that showed them something new or unexpected. Maybe sometimes they made that choice because they were specifically interested in writers of color. Other times, I suspect they simply responded to what was there.

This suggests that racial bias, like gender bias, is less prevalent when power is distributed. Which begs the question: What needs to happen in theatres across the country to bring the same kind of diversity on our stages? What can artistic directors do? What can funders do? What can artists do? What can audiences do? We need to take to heart what Yong said: passive concern is never enough.

Peter Diamond and Alex Wu in Pond Life by Elyne Quan, Brandeis University. Photo by Mike Lovett.

Back to Climate Change

Why does this matter in the context of climate change? Because discrimination, economic and environmental injustice, and resource depletion are all manifestations of the same system gone awry. And to change that system, we can’t just tinker with individual elements—we have to rethink the whole synergetic mess. I’ve written about this before, here and here: how we make theatre is just as important as what we put on stage. CCTA is a case in point: with one small structural change at one end of the process, where communities are given the power to decide which stories they want to hear as opposed to having that decision imposed on them by an artistic director, we’re able to have a significant impact on representation at the other end. Now just imagine what would happen if we applied this same principle everywhere.

I’m grateful to Yong for inspiring me to go through this exercise. I hope that, in turn, this article inspires others to do the same so that together we can continue to advocate for the kind of systemic change we so need. And as I enter another CCTA year, I look forward to collecting new data (something I never imagined I would hear myself say) to see what else we might be able to learn.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here