Like many artists, the pandemic first affected me personally through a wave of cancellations. Initially, it was all of the work I had for March, then through the end of May, and finally all the way through the summer. These cancelled productions represent years of work and a huge chunk of income. Along with the cancellations came the first dire predictions of a post-COVID world—that the arts would be the last industry to open up. Soon my colleagues began experimenting with moving their performances to Facebook Live, but to me it didn’t feel like quite the right solution to maintaining live performance in the face of physical distancing. It reminded me of one of the discussions we have in the history of electroacoustic music class I teach at SUNY Purchase: how people first adopt new technologies. At first, we try to map older practices onto new technologies, even when they aren’t a good fit.

This is what I saw with the livestreams: our traditional modes of live performance are not a good fit for the new world we find ourselves in. Rather, as we continue to create live performance in the months ahead, we must seek new modes of performance that actively engage with the technologies we’re using.

To explore what this new medium might afford, I once again joined librettist Rob Handel and director Kristin Marting (with whom I’d created the techno-noir opera Looking at You, a piece that featured live data mining of the audience) to compose a musical experiment. The result was called “all decisions will be made by consensus,” a short opera performed live over Zoom. The performance was also livestreamed to HERE Arts Center’s Facebook page as part of their #stillHERE series.

We chose to work with Zoom as it had the best onboard audio settings for a ready-made teleconferencing platform with video, it allowed multiple performers to be in the same performance space, and it also allowed us the most interaction with our live audience. One of the challenges of livestreaming is that the performers don’t have the same sort of connection with the audience, but on Zoom the cast can see who is present. Additionally, its webinar platform had built-in permission levels that are different for actors and audiences (which comes in handy for security reasons, as I’ll discuss in a bit). There are open-source platforms like Open Broadcaster Software (OBS) that offer more flexibility with regard to the visual output, but these platforms require more setup on the performers’ end than we wanted to ask them to do. Additionally, we did not really have a budget for sound, set, and costumes, so we were working with what people had in their homes.

As we continue to create live performance in the months ahead, we must seek new modes of performance that actively engage with the technologies we’re using.

Working with Zoom

Once the decision was made to use Zoom, our first step in creating the piece was to do a series of audio tests. Zoom has the ability to share just audio directly from a computer, as it would during a screen share, but without the visual of the screen. I had done some experimenting on my own and found that I could play audio directly from Ableton Live (the digital audio workstation (DAW) I used to create the piece) through the Zoom interface. The benefit of doing it this way is that there’s a clearer audio signal.

In the audio tests, I wanted to see what the variability in latency was between listeners. I was controlling the backing tracks from my apartment in the Bronx while Paul An, one of our cast members, called in from New Jersey, Kristin was listening in from Manhattan, and Rob was listening in from Pittsburgh. For the first audio test, I asked Paul to count along to a four-beat pulse. We quickly discovered that everyone was experiencing the relationship between Paul’s voice and the beat differently—I heard Paul’s “one” lining up with the fourth beat while Kristin heard it on the first beat. What this meant was that each audience member would have a different experience of the audio. And it makes sense, if you think about it. We each have different internet connections with different speeds, and the distance from the sources of the audio (Paul in New Jersey and me in the Bronx) to the listener will vary.

My task, as the composer, was therefore to create music that would work with this variability. This also meant building the variability into the libretto. Rob wrote a script that was structured around the idea that there would be sections where multiple voices would be overlapping and sections where a solo voice would emerge. There is also a lot of repetition built into the text, with the understanding that it will probably be incomprehensible during the overlapping sections, but will have moments where it emerges into clarity.

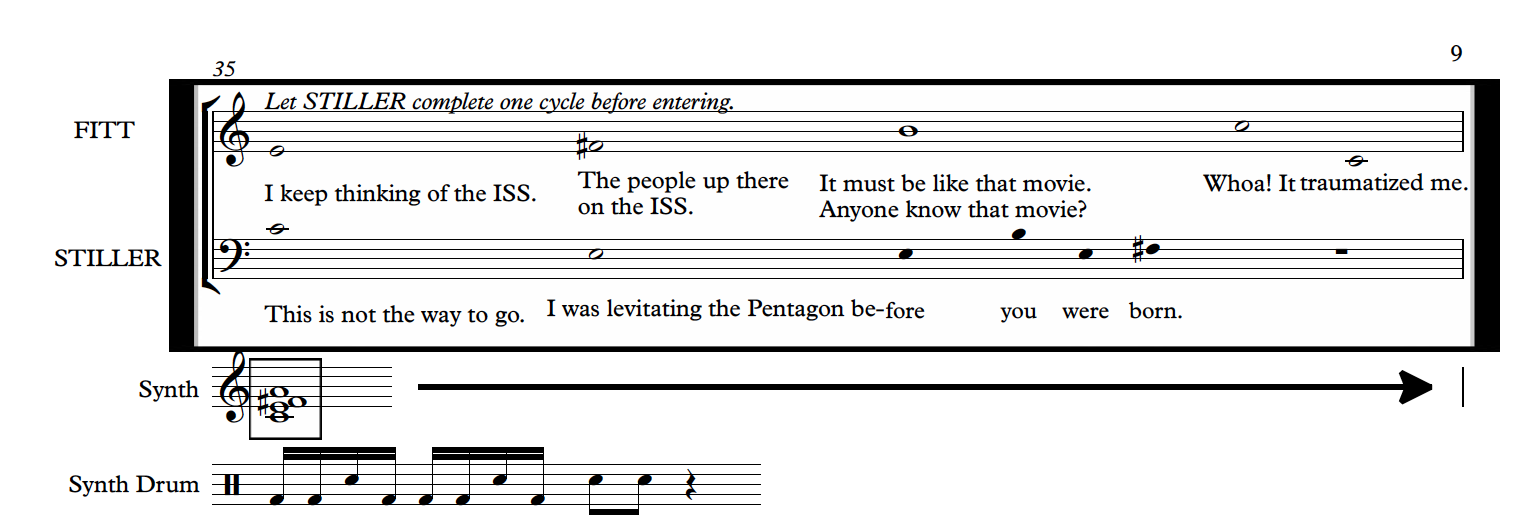

I structured the piece as an aleatoric score. The word “aleatoric” takes its root from the Latin word meaning dice and just means that it has some element of chance built in. The chance elements in the score included the rhythms of the singers’ vocal lines and how those vocal lines lined up with the underlying accompaniment.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Very helpful! Wondering if you know about the Bard/Fisher Center production of MAD FOREST, directed by Ashley Tata. Used Zoom quite brilliantly.

Thanks so much, Kamala! So detailed and so useful!