Afro-Cuban History in La Sirene

Rutas de Azucar / The Siren: Sugar Routes

On November 25, 2016, the infamous Cuban leader Fidel Castro died at the age of ninety. It closes a chapter in Cuban history, and signals the end of an era. The roots of revolutionary zeal did not begin with Castro, however. Before Castro, someone else wore the mantle of “The Father of Cuban Revolution.” Over two centuries ago, the zeal brought on by the desire for freedom already existed. Before communism took an ideological turn throughout the world, the revolutionary fervor that burned strong and true in the first freed colonial stronghold in Haiti in 1803 spread through the other Caribbean and Latin colonies pushing subjugated and marginalized peoples to fight for their sovereignty. The spirit of the Haitian revolution was already in the hearts and minds of its people, especially the dissident artist and free colored José Antonio Aponte who was executed by the Spaniards on April 9, 1812 for leading a failed black revolt against the Spanish occupation.

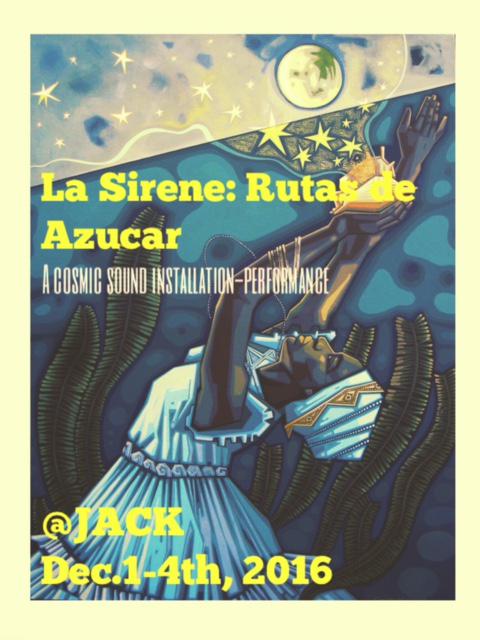

Here is where Afro-Cubana multidisciplinary artist and scholar Jadele McPherson and her ensemble Lukumi Arts explore the Black history of Cuba. Her recent project La Sirene: Rutas de Azucar (The Siren: Sugar Routes), directed by Charlotte Brathwaite, performed at Brooklyn’s JACK Theater. Lukumi Arts shares:

La Sirene: Rutas de Azucar probes Cuban revolutionary José Antonio Aponte's libro de pinturas, a book of paintings, of black heroes that served as a catalyst for an attempted rebellion against colonists, leading to the first conspiracy and abolition charge in Spanish-speaking Latin America. Through sound and movement, McPherson maps the connections between West Indian and Haitian migrations to Cuba to harvest sugarcane, and repositions the Cuban ingenio (the sugar mill) as a birthplace of freedom that extends beyond borders and water.

“Where are you from? What’s your name again? Aren’t you just black? But that’s not Spanish. Say something in Spanish. Now say a whole sentence in Spanish.” These questions and comments and iterations of these questions belie the intention of the questions, which is: who are you because you don’t look like who you say you are, that the blackness she and these other performers represent is isolated to one definition of blackness. Thus begins the performance with a tone of inquiry. McPherson acts as the Master of Ceremony and opens the immersive production with these lines superimposed on each other, a cacophony about identity along with two other performers (Yomaira Gonzalez and Maxine Montilus) who transform as American travelers who have roots in Cuba. The scene changes immediately through McPherson’s rapid-fire Spanish as she becomes the Cuban passport control officer asking around the room first to the two other performers traveling to Cuba to visit family, and then to the audience: Cubano o Americano? McPherson demands a response from the audience members whom she approaches to give an answer about their identity to show that Cubans and Americans are treated differently, but especially Cubans who have left Cuba to become American. A heated exchange ensues in a mixture of Spanish and English between the passport control agent and the young woman (played by Gonzalez) who was “born in New Jersey” planning to visit her family in Cuba.

Passport Agent: Cubano o Americano?

Young Woman: Americano? Cubano? Both? I don’t know. My family is here.

Passport Agent: No, no…you Cubana.

Young Woman: I was born in New Jersey. I’m just visiting family.

Passport Agent: Go to Cubano line.

Here is the crux of this work: do we enter it as Cubans, Americans, or something in between? Identity is a fluid state in this world that we inhabit, and it is reflected and refracted in the world of Lukumi Arts’ La Sirene. In this moment of exchange between the passport agent and the young woman, we are thrust into the world and the permutations of identity of an exile or, more specifically, the experience of the child of exiles. Is a person’s identity tied only to her passport or to her family’s cultural identity? Why is she made to define herself?

We are taken on a journey where we are swallowed by music, dance, and ritual where one’s identity shifts in time and space.

For an Afro-Cuban, the landscape of this production is home since most of the production is in Spanish with some English, and Haitian Kreyol. It doesn’t matter, however. Through theatrical sleight-of-hand—the soulful singing of McPherson, Caridad Paisan Garbey, and performances of other members of the ensemble (Val Jeanty, Yomaira Gonzalez, Maxine Montilus, Nathalie Guillaume, Hansel Vaillant and Daniel Gil), one feels the other-worldliness of the piece. We are there to witness and to experience.

We are taken on a journey where we are swallowed by music, dance, and ritual where one’s identity shifts in time and space. Just as some members of the ensemble mutate to American, to daughter of Aponte, to wife of Aponte, to sister of Aponte, and to the mother of the revolutionary hero, we are drawn in to transform ourselves through the undeniable beat of the music, the hypnotic movements of the dances, and the cadence of the words being spoken regardless of whether one knows the meanings of the languages or not. Even men turn to gods in this piece just as one of the ensemble members transforms to Chango (the orisha who represents fire, lighting, thunder, and war as well as male virility, passion, and power) through mask, movement, and ritual. We join, through experiencing the spectacle, in the revelry.

This explosion of rhythm, color, and movement is presumably referenced from Aponte’s book of paintings—a visual tome with a rich tapestry of Black kings, priests, and figures of authority. The book of paintings is purportedly lost or destroyed due to the nature of the allegations against Aponte. The only thing left to posterity is the intertextual descriptions, the accounts of Aponte’s interrogators who describe the work they find offensive. Conjuring the lost book is an act of alchemy, producing something tangible from the ghost of something that once was. In his essay on Aponte’s lost book, scholar Jorge Pavez Ojeda sees that Western tradition places primacy on the written text and the written alphabet, and the power that oral tradition and pictorial representations of thought that Aponte employed in his codex of images flouted and violated the control of colonial authority. Ojeda writes, “the judges attempt(ed) to control any possible dissemination of the ‘meaning’ of the paintings, by making the book and the author disappear, leaving the trial record as the only remnant and trace of their existence.”

This dissemination of ‘meaning,’ however, is not lost. The spirit of Aponte’s revolution continues because it is not the beginning.

This dissemination of “meaning,” however, is not lost. The spirit of Aponte’s revolution continues because it is not the beginning. Aponte drew upon the oral histories of his people tracing his genealogical narrative back to Africa. It is an inquiry that McPherson also channels in La Sirene, and we see this when one of the young women played by Yomaira Gonzalez ask Caridad Paisan Garbey, who plays the mother and grandmother figures, about the meaning of La Sirene. Who is she? The grandmother replies that to know The Siren can make a person go mad. The Siren is a revered figure, honored as the spirit granting safe passage in the journeys to a person’s destination, and Gonzalez participates in a ritual that opens her up into a state of frenzy as though the spirit has taken hold of her body because history is not something just read about, it is also metaphorically and literally embodied.

In the end, the three women—McPherson, Gonzalez, and Montilus—end the piece with a litany, a prayer for their being, at the end of this journey to the heart of their identity, again in words and phrases superimposed on each other as they are blessed by the orishas. I am Black and I am beautiful. Yo soy negra. They affirm their Black identity and the beauty in that blackness.

Now, as icons like Castro die, and as the world and our understanding of the world and its history continue to change and realign, it is good to acknowledge that journeys do not just end when a show does. The questions certainly don’t.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here