All the Hip-Hop World’s a Stage, and the Critic Is a Player

I get plenty of surprised looks when I tell fellow theater critics that I also write about hip-hop, but the line between actors and rappers is drawn with an extra-fine-point pen. For as much vitriol that’s been heaped on rappers, they’re really just in-love-with-words nerds who spent a lot of alone time as kids creating fantastical worlds and powerful alter egos for themselves. Sound familiar?

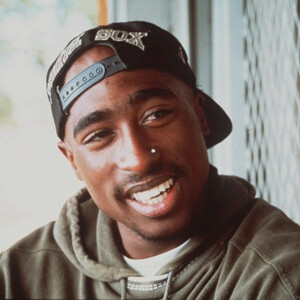

Consider Tupac Shakur. The late rapper was more than a triple threat, with natural charisma, a sharp intellect, the ability to craft a startlingly realistic character while remaining deeply vulnerable and a voice that could elicit tears in listeners in one song and raucousness in the next. Outside of his music, he’s remembered for his outsized personality. Leaving a courtroom once, he spat into a reporter’s camera. On one of the last songs released before his death in 1996, he’s so animated he almost sounds delirious. He was a natural ham in front of the camera, and appeared in several movies to favorable reviews. If he hadn’t been gunned down prematurely at the age of twenty-five, safe money is that he would’ve had a longer career as an actor than a musician.

Tupac is an easy example; he acted when he was a child in New York and later attended Baltimore School of the Arts. But take one of the most feared groups in rap history, N.W.A. Yes, police often shut down their concerts and radio banned their songs. But they weren’t perpetrators of the crime and violence in Compton; they were giving eyewitness accounts of the tempest in an area that most real news reporters were scared to enter. N.W.A. just as easily could have acted out their scripts onstage instead of rapped them.

Different artistic mediums, same desired outcome: to draw attention, to evoke emotion, to inspire thought.

Because words are at the heart of both rap and theater, the approach I take to both is similar. What’s the artist/playwright trying to say? How successful are they in delivering that message? How is that message helped or hindered by the actor/artist doing the delivering? How do the production values (light/set/costume/sound design in the theater, the beat for rappers) complement the words, the voice, and the performance?

Yet given all the two have in common, there is a huge difference in how each art form’s artists, readers, and critics engage, and it has everything to do with rap’s much more developed presence on the Internet.

Different artistic mediums, same desired outcome: to draw attention, to evoke emotion, to inspire thought.

A bit of history: The advent of Myspace (full disclosure: I am currently employed as a staff writer for the company) in 2003 is heralded as the beginning of rappers using the web as their own (rent-free!) office. Unknown musicians began uploading their songs to the social networking site and connecting to, and soon collaborating with, other artists. One site led to another (YouTube, Twitter), but one thing stayed the same: Rappers were the early adopters. Hip-hop is a youthful culture and the young are savvier with technology. Hip-hop in the early 2000s had become bloated with money, so those looking to break in without cash had to be savvy and enterprising. Production programs on the web, like Fruity Loops, were easily accessible, and now there were easy platforms for distribution. All a wannabe rapper needed was a computer.

What does that heavy online presence mean for those of us who write about rap music? Extreme engagement from both artists and readers. One of the first reviews I wrote in L.A. was of a DJ set by Questlove, drummer for the Roots, the house band for “Late Night with Jimmy Fallon.” I had, at most, a couple hundred followers on Twitter and had written the piece for a university’s website. Yet the very next day, Questlove tweeted me defending his set. Admittedly, I don’t write about Broadway shows, but I find it hard to believe that Laurie Metcalf would tweet some grad student to take issue with his negative review.

As for reader engagement, you don’t know what wrath feels like until you’ve written a piece on the best Los Angeles rap albums of the year and almost felt readers’ hot spittle on your face as you scroll through comments. I’m sure Terry Teachout has gotten hell for his scathing reviews in the Wall Street Journal, but I wonder if anyone has ever directed him to “kill yourself” in the comment section.

Thank God, right? But there is value in this sort of intense engagement. The passion it signifies is part of why hip-hop culture is still a force to be reckoned with. It shows people care, and care deeply—and as we all fret about the future of theater, that’s something we could use a little more of.

I know, I know, more people listen to music than go see theater. Why? Because music is cheaper and more accessible. The obvious answer is to take theater offstage and put it online. That makes it not theater, you say. Fact is, even hip-hop fans, who download most of their music for free, still cherish and spend money on the live experience. New Orleans rapper Curren$y hasn’t had a song on mainstream radio, but he packs the house on an almost constant tour schedule. Tickets to Coachella sold out so quickly that the festival added another weekend last and again this year; tickets to the first weekend sold out in fifteen minutes.

Why can’t we drum up so much anticipation for say, the Humana Festival of New American Plays that Actors Theatre of Louisville extends it to two months? Transform the city into South by Southwest, only for all live performance instead of just music (something like this is already brewing via Motherlodge). “Spring break for theater geeks” has a ring to it, don’tcha think?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

dope.

To cite another example of artists making their work available online, the visual art community has been posting pictures of their work on the web for years. Despite being an object, there is nothing like standing in front of a painting or sculpture, and yet museums and artists create online exhibits and archives to share with fans and enthusiasts. I have my reservations about recording theater. In the early 20th century, when audio recordings were There was a long debate about how recording music would change the nature of the music and the experience. National Live and MET Live have both embraced this ethos.

If Tupac was still alive today he would be more than an artist, he would have continued his activism and found solutions to the Prison Industrial Complex and much more. Rappers like N.W.A were more than witnesses and interpreters of their hood stories, especially Eazy E! He was his hood. Actors act and some mega commercialized rappers pretend, but the artists you are speaking of were participants in their COMMUNITY! No script needed. These artists knew the people in their community! Theatre people do not generally! We use people when we need them to go to a play!

Death threats come with the territory. One local performer actually emailed me to say he would "find me and hurt me." Others (from a gay company no less) have emailed that they "hoped I got AIDS and died." A local director was so menacing in the lobby of a local theatre that I had to warn him I would request a restraining order if he ever came within fifty feet of me again. When I approached rap fans standing in line for a Beenie Man concert to ask questions about his homophobia I was almost physically assaulted by two or three men who shouted repeatedly "Are you a faggot? Do you suck cock?" And yeah, I've gotten the witty "Why don't you drop dead?" dozens of times in the comments section. It only makes claims regarding the "cruelty" of critics even more amusing.

I once received a comment on a theatre review that ended with "I hope you die." Interesting, to say the least.