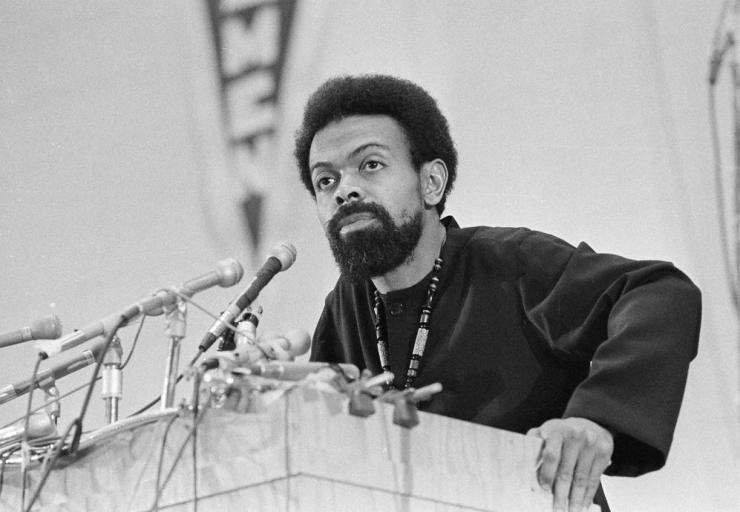

A "Ballot or Bullet" Art

The Legacy of Amiri Baraka

This is part of a series of tributes for Amiri Baraka (1934-2014), poet, playwright, novelist, music critic, and political activist.

In his autobiography, Amiri Baraka, born Everett LeRoi Jones in 1934, describes a stunned moment of self-discovery after reading a poem in the New Yorker. Baraka, then a twenty two-year-old aspiring poet, is confronted with a vast gulf between his reality and the sentiments and aesthetics of the poem, not to mention that of the New Yorker itself.

…Gradually I could feel my eyes fill up with tears, and my cheeks were wet and I was crying like it was the end of the world… I realized that there was something in me so out, so unconnected with what this writer was and what that magazine was that what was in me that wanted to come out as poetry would never come out like that and be my poetry.

A decade later, in his manifesto poem for a black political and artistic renaissance, Baraka would give his own succinct definition of poetry, a far cry from what he had encountered in the pages of the New Yorker: "We want poems that kill/Assassin poems, Poems that shoot guns."

I bring up the New Yorker example to simply emphasize Baraka’s singular role in orchestrating a new kind of literature from the messy and indecorous world of politics, a new art that gave vent to the black experience in America at the height of the Civil Rights movement. He rapidly went from being an outsider to one of the most urgent voices of political rebellion and literary avant gardism in mid-twentieth century America.

He rapidly went from being an outsider to one of the most urgent voices of political rebellion and literary avant gardism in mid-twentieth century America.

In the late fifties, Baraka began to turn the wise-cracking, sardonic, insurrectionist voice of his poems into dialogue for the theater. Decades later, in an interview with Maya Angelou, Baraka would describe a spontaneous transition to playwriting as his poems turned into conversations or “dialogue poems.” “As I began to get more and more of a distinct sense of myself as an insurgent—trying to be some kind of insurgent force—I found that my words, which were at first lyrical became more like conversations.” The crowning achievement of Baraka’s playwriting career came rather early with his 1964 play, Dutchman. (According to Baraka, his first play was written in his early twenties. A Good Girl Is Hard to Find “was written in reflection of my generally womanless state”).

The five decade old Dutchman, although it speaks of race relations of a different generation, also possesses timeless insight and prescience. The recent tragic Florida shootings of Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis, both unarmed, young black men, bear an eerie resemblance to the Dutchman’s portrayal of urban dystopia and violent animus in that most banal of modern settings, a subway car. The play, like no other work of modern art, portrays the dynamics of violence and racial conflict that seethe just beneath the urban social fabric as strangers unexpectedly meet, collide, and transform into executioners and victims.

In the play, the teasing, amorous banter between Clay and Lula, a young African American man and a white woman, quickly escalates into a racially charged confrontation and ends with Lula murdering Clay with the tacit support of the other white subway passengers. In 1964, the play’s unfiltered visceral outrage against racism shocked contemporary critics unused to such a no-holds-barred excoriation of white America.

In this Obie award winning epic of the Black Arts movement, Baraka gave us an extraordinary story steeped in both the language of manic surrealism and an unfaltering social realism—it was the sophistication of modernism married to the movement of black empowerment. Baraka would go on to write other plays on race relations and the history of racial injustice through the sixties: The Slave, a controversial play of black militancy whose setting is cannily reminiscent of apartheid-era South Africa; the charged urban drama of gang violence and interracial homosexual love set in a high school lavatory in The Toilet; and the emotionally brutal and arresting allegorical tableaus in Four Black Revolutionary Plays.

While Baraka’s work would turn out to be deeply controversial at times, there is no denying his lasting impact as a poet and playwright. Critic Arnold Rampersad ranks him with the likes of Frederick Douglass, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and Ralph Ellison as “one of the eight figures who have significantly affected the course of African American literature.” There were many streams and tributaries that shaped and contributed to Baraka’s remarkable art: The hip iconoclasm of mid-century Greenwich Village and Lower East Side, Beat poetry, the Civil Rights movement, the Cuban revolution, jazz, and the death of Malcolm X, the last doing more than anything else to radicalize Baraka.

Following Malcolm X’s assassination, Baraka left his moorings in East Village and moved to Harlem where he spearheaded the formation of the revolutionary Black Arts movement and the Black Arts Repertory Theater School, where his plays, Toilet and Experimental Death Unit#1 were produced. In the image of the cold-blooded killing of Clay, the bourgeois, liberal, assimilated young black, at the hands of those he instinctively trusts, one can easily detect the influence of Baraka’s own spiritual withdrawal from the largely white, bohemian artistic enclave of the Village and his renewed personal and political commitment to black self-determination. And although this political and artistic trajectory would often get mired in controversy, elicit censure and cause discomfort, Baraka also performed astounding and deeply important work during this phase of his artistic career.

Among other achievements, Baraka excavated the roots of jazz music in the monumental Blues People (written two years before Malcolm X’s assassination) and perfected a stunning avant-garde expressive mode for black experience in America in his plays and poetry. Decades later, Baraka would sum up his historic endeavor with the short-lived Black Arts Movement, “We wanted an art that was revolutionary. We wanted a Malcolm art, a by-any-means necessary poetry. A Ballot or Bullet verse. We wanted ultimately to create a poetry, a literature, a dance, a theater, a painting that would bring revolution.”

I was fortunate to have been present for a poetry reading by Baraka at the famed Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church in the Lower East Side last year. Small and piercing, Baraka regaled a packed room with his bold, defiant, acerbic and profane “lowku”—his version of haiku. The occasion felt historic and nostalgic, carrying with it a whiff of the radical countercultural politics and social activism of 1960s New York with which some of Baraka’s best work had been so closely allied.

***

Image: Amiri Baraka speaks during the Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, 1972. AP Photo by Julius C. Wilson

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Love this.