In the exhibition, Murphy and Hamilton contextualized St. Denis and Shawn’s complicity in racism and colonialism in the earlier half of the twentieth century, when their cultural appropriation was not challenged but was considered politically radical and innovative by certain mainstream white American and European critics and audiences. Simultaneously, the curators open space to celebrate and acknowledge the importance of their work and how their legacies continue to build venues for all artists to be heard on the mainstages of dance.

The dance pioneers’ achievements include having defined dance styles that were distinctively American, foregoing European traditions by dancing “in bare feet, often flexed…in parallel instead of turned out, and making full-body contact with the floor”; practices that are still recognizable today in many contemporary dance traditions globally. The duo more importantly supported global artistic collaborations, which allowed international artists, including artists of color, to come to the country throughout the twentieth century.

As a theatre and dance dramaturg, I noted how Murphy and Hamilton struggled to simultaneously celebrate and criticize our humanly flawed artistic ancestors. The exhibition didn’t always find the right balance but showed promise of how we can potentially better confront our shared problematic theatrical histories and help us better imagine how to create open discourse around representation despite its messiness and complexity.

Rediscovering Historical Objects

The Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival is the longest-running international dance festival in the United States. An incubator of new work by diverse communities of American and international artists, “the Pillow,” as it is lovingly referred to, houses extensive archives of dance paraphernalia from the entirety of its history. The festival has become home to diverse artists from around the world throughout its nearly eighty-seven seasons; it became a National Historic Landmark in 2003 and was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 2011 by President Barack Obama.

In summer 2017, Hamilton started interning in the festival’s archives department. As a professional costume and dance historian and mounter, she was intrigued by the costume collection—thirty-six trunks full. “The trunks revealed an incredible time capsule full of costumes, headdresses, shoes, props, and accessories [of St. Denis and Shawn],” she shared. Hamilton and Murphy began using photographs of dances and other ephemera to help identify full costumes and start building an exhibition around them, for both Denishawn Dancers and Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers. Hamilton catalogued nearly two thousand five hundred found items into the archives.

Stage costumes give us access to artists and their artistry, but also to a period’s cultural sensibilities around design, fashion, race, gender, sex, and identity politics.

Negotiation of Narrative

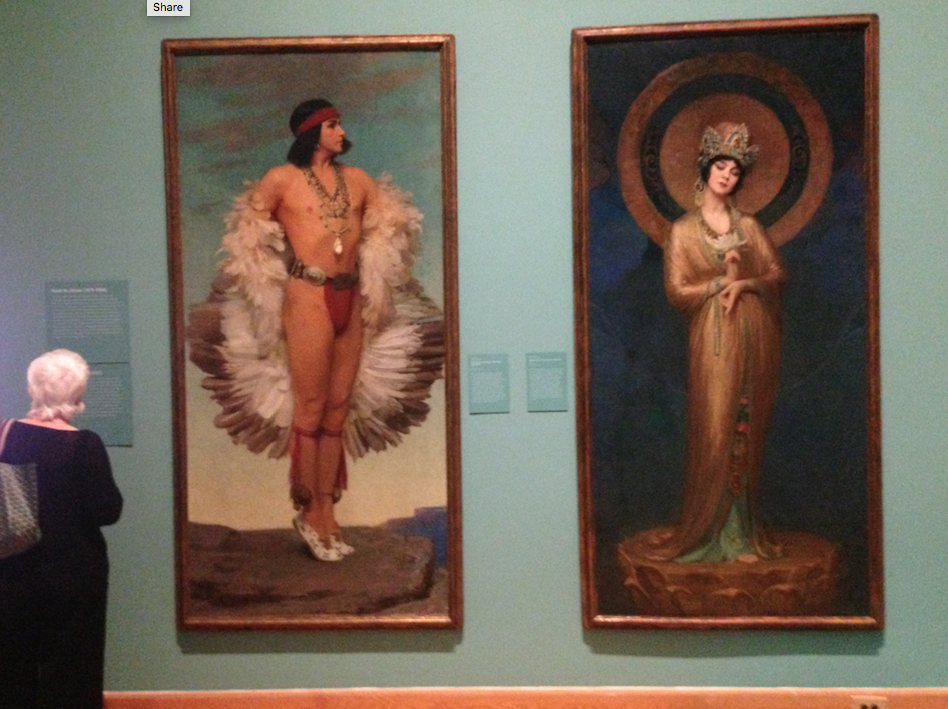

St. Denis and Shawn’s arguably most important contribution to American dance was the creation of their Denishawn School, the first of its kind in the country to train and produce a professional modern dance company. Some of the original costume pieces from Denishawn were prominently exhibited, such as the costumes for Kuan Yin (1919) and Feather of the Dawn (1923). These costumes played a role in helping the dance pioneers establish dance as an important and respected artform in the United States by white Euro-American critics and audiences. In Kuan Yin, St. Denis attempted to explore themes of Eastern religion and a spiritual dance experience. As such, she costumed herself mostly in jewelry that she believed captured an essence of the East Asian Bodhisattva of Compassion. In the latter piece, St. Dennis and Shawn created a work around Native American cultures when the United States government was actively erasing Indigenous communities.

As explained in the exhibition’s press release: “St. Denis and Shawn’s appropriation of non-Western and Indigenous forms of movement was a search for more authentic modes of self-expression than many in their predominantly white and upper-class circles believed existed in the industrialized West.” Within the contexts of when they were first choreographed and presented, these two dances were culturally subversive for a white American audience. However, neither dancer attempted to replicate movements specific to the cultures they were borrowing from, nor imagine their implication in a larger systemic oppressive power.

As an artist of color, it was impossible for me to separate the duo’s artistic creations from the continued marginalization of certain communities and cultures. Looking particularly at the costumes and artifacts from the so-called “Oriental ballets,” I had a difficult time not seeing how these practices of “cultures as costumes” were reminiscent of contemporary “accepted” racist practices in the performing arts. I also weighed St. Denis and Shawn’s intentions within the context of their time. It is evident that, during their travels, they studied with the masters of different dances throughout the world, collaborated with them, learned from them, and shared with them their own dance techniques. However, I wasn’t sure what to make of my feelings, because I wasn’t sure for whom the exhibition was made.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here