Color-Conscious Casting

Three Questions to Ask

I’ve got a big fat opinion on the term “color-blind casting,” which is that it doesn’t exist. I can’t think of an environment, in real life, where race doesn’t factor into relationship dynamics. And if it doesn’t exist offstage—why do we think we can (or should) create that scenario? I prefer the term “color-conscious casting,” by which I mean that race is acknowledged in, and ideally deepens, theatrical conversations.

As someone who’s taken to directing canonical work as of late, I delight in the opportunities that color-conscious casting can provide, for both actors and audiences. Two years ago, I directed a reading of Closer by English playwright Patrick Marber at Victory Gardens Theater with an entirely Asian American cast. Afterwards, an audience member said, “You know, I was watching this play and trying to figure out what statement you guys were making, why this play had to be done with an Asian cast. Why couldn’t they just be people? And then I realized that that was probably your point.” And honestly—it was. We weren’t pushing a larger agenda, and race wasn’t the focus of that process, even though it was the main thing some audiences saw on stage. That artist-audience disconnect can be exciting and challenging, as it was in this case; I’ve also seen productions where it was reductive and upsetting.

Asking three specific questions tends to clarify the storytelling and avoid potential pitfalls when considering casting, race, and the story of the play: 1) What story does this racially conscious casting tell? 2) Is the new story appropriately complex? 3) Do I have the right players to tell this story?

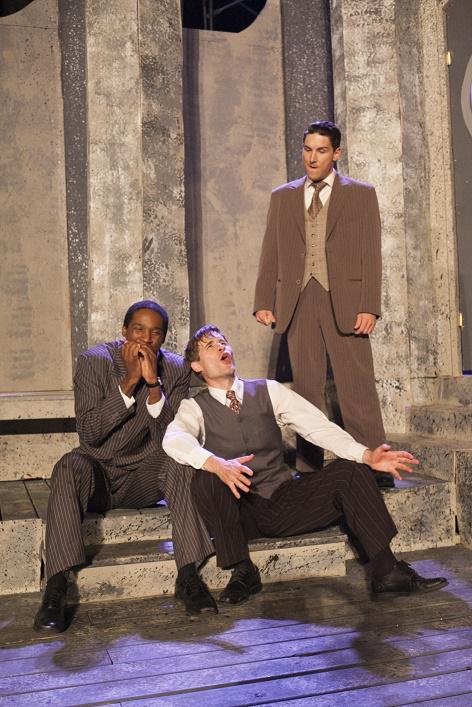

and Luke Daigle (left to right). Photo by Michael Brosilow.

As a professional director, I’ve helmed two Shakespeare productions with color-conscious casts in the last year. First, I directed a Bollywood take on Much Ado About Nothing for the South Asian focused Rasaka Theatre Company, featuring a South Asian Beatrice opposite a white Benedick; and most recently, a prohibition era, gangster Chicago setting of Hamlet with a white Hamlet and a black Horatio. Currently, I’m in pre-production for my thesis production at The Theatre School at DePaul University with John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi, a Jacobean drama about the widowed Duchess and her two brothers, Ferdinand and the Cardinal, who seek to prevent her from remarrying the man she loves and plot to kill her. My designers and I decided to set the play in the New South Era (about fifteen to twenty years after the end of the Civil War). This most recent venture is the most racially complex resetting of a canonical play I’ve tackled to date, and—particularly in an academic environment—I’ve had a lot of candid conversations about casting, race, and how that will change (and potentially override) the story of the play.

While I’m always happy to have those conversations before, during, and after the production process, I’ve noticed that asking three specific questions tends to clarify the storytelling and avoid potential pitfalls. They are 1) What story does this racially conscious casting tell? 2) Is the new story appropriately complex? 3) Do I have the right players to tell this story? We have to ask these questions of our entire collaborative team, early and often. For The Duchess of Malfi, the process went as follows:

1. What story does this casting tell? Is it clear and supported by the text?

At our first production meeting on September 7, we began by talking about story and style. I talked about the play’s themes of power (and abuse of it) and compared it to blockbuster “takedown” movies like Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds. We then brainstormed a list of sources of power and privilege in traditional, hierarchical societies. The list included gender, race, money, political or religious office, information/spying, sexuality, reputation, and bloodlines. I pointed out that the play, as written, already depicts characters abusing all of those types of privilege, except racial. Setting our production in the post-Civil War South adds that aspect to the play’s mix in a major way—a decision we felt was only fitting.

Given the racially charged time period we’d landed on, I told my team that we would have to have a frank conversation about the casting of this project. We started with an exercise first introduced to me by Dick Block at Carnegie Mellon University. We listed all of the characters in my cut on a dry erase board and brainstormed who might play those roles in the “dream” version—based on Hollywood or Broadway actors, Chicago folk, other people we might know or have seen perform. The exercise is designed to get us talking about what qualities the characters have, without getting bogged down by the format of traditional casting breakdowns.

I told them to ignore gender and race for the time being. Surprisingly, the first two “dream” actors to play Ferdinand, the Duchess’s possessive and lust-ridden brother, were women—Sarah Michelle Gellar and Glenn Close.

I then asked the team, “OK, given what we know about the power dynamics of this time period, what decisions have to be made in the casting of this play?” The dramaturg proposed that the characters with most power—the Duchess, Ferdinand, and their brother the Cardinal—needed to be white. The room agreed. If we’re looking to tell the story of a takedown, we need to tell a clear story about who’s at the top of the food chain, and in this case it simply had to be a white, male-dominated family.

2. Is this story appropriately complex?

Having made those three decisions (out of a cast of eleven in total), I then said, “OK, we know who needs to be white. Are there any roles we know must be played by actors of color?” My lighting designer offered up her instinctual response—Antonio, Julia, and Bosola should all be played by African American actors.

I was hesitant about the choice of casting a black actor as Antonio, the Duchess’s secret husband. Does the idea of a mixed race hidden marriage seem a cliché in this setting, I wondered? Does it then make the play all about race? The dramaturg’s faculty advisor, Ernie Nolan, asked me, “What about the Duchess? Does it reduce her sexual power? Oversimplify the love story?” On the other hand, I felt the choice was 110 percent supported by the text, in which the Duchess’s brothers lament the possibility of her corrupting their bloodline: “Shall our blood / The royal bold of Aragon and Castile / Be thus attainted?” (Act II, Scene V, lines 22–24);

and Antonio is warned against behaving like a social climber: “Oh, sir, you are lord of the ascendant, chief man with the Duchess… what of this? Search the heads of the greatest rivers in the world, you shall find them but bubbles of water. Some would think the souls of princes were brought forth by some more weighty cause, than those of meaner persons; they are deceiv’d…” (Act II, Scene I, lines 99–107). Those are givens in the text that the updated setting supports.

I paused this conversation to talk about the other characters. What about Antonio’s best friend Delio? “Where does he fall on the spectrum?” I asked. When the team proposed that a white actor play that role, something clicked for me. “If we have two positive mixed race relationships in the room—one sexual, one platonic—that’s an interesting story,” I thought. “That makes things much more complex.”

We shifted our focus to the Cardinal’s mistress, Julia. “What I like about putting a nonwhite actress in this role is that it makes the Cardinal totally hypocritical,” I said. Nolan pointed out a potential problem—we then have two actors of color in the role of “lust objects” for the white Duchess and Cardinal. I felt my heart drop—I don’t like that story, I thought. Then I realized, but of all of the characters, the Duchess is the one who’s the most lusted after (and by her own brother, of all people). The world is filled with desire of all kinds—including the clandestine and incestual. That’s in the text.

I think we sometimes back off of bold casting choices for fear of telling a reductive and/or oversimplified story. As a South Asian American, I’ve often felt frustrated by the lack of my community’s stories on stage; what’s even more frustrating is feeling that, when that story is being told, it relies on stereotypes or caricatures as opposed to challenging those mainstream perceptions. Through my conversations about The Duchess of Malfi, what I’ve realized is that color-conscious casting choices don’t become reductive if we use them to tell a story that includes multiple perspectives.

In this case, I realized that we’re not telling a story about black people being exotified lust objects if almost everyone in the play—regardless of their race—is being lusted after. Nolan mentioned another concern, “Are we reducing Ferdinand and the Cardinal to white racists? How do you justify their hatred of the Duchess’s marriage?” I offered up that with a black actor in the role of Bosola, who is also initially opposed to the marriage, I thought that would be less of an issue. I did have a problem though—I wasn’t sure I’d be able to find that actor in DePaul’s limited casting pool.

3. Do I have the right players?

The casting pool at The Theatre School at DePaul University is known for being quite diverse, and seven of the thirty-one men in the acting company are African American. The challenge is that other productions have racially specific casting needs at the same time, including Nolan’s production of The Day John Henry Came to School. This will limit my options. Moreover, auditions are almost six months out, and I haven’t had the opportunity to gauge the language skills of half of the acting company, who have yet to start their classical acting training at DePaul.

“I think we have to walk through all possibilities with Bosola—black, white, or mixed—and see if we still like the story we’re telling,” I said. “It’s the hardest role in the play to cast—full stop. I have to be able to consider as many actors as possible for the role.”

Continuing to focus on the story, and not the specific implications of actor X as opposed to actor Y, we mapped out the play on the dry erase board. What began as a simple list started to resemble a football coach’s game plan, with arrows drawn back and forth indicating the various relationships. Like one of those logic grid puzzles, we came up with a lot of cause-and-effect “if” statements, including:

- If we have an African American Bosola, our dual protagonists (Duchess and Bosola) are both minorities, which is a statement we like.

- On the other hand, if we have a white Bosola, his change of heart from disliking Antonio to defending him is stronger and serves as a meatier counterpoint to the Cardinal and Ferdinand’s story.

- If we have a white Bosola, then at least one other actor other than Antonio must be nonwhite. That could be Julia, or someone else entirely, but we want to make sure the story we’re telling with our casting is appropriately complex.

- If we have a black Bosola, there’s language like “saucy slave!” in the text that becomes extra charged.

We left the room without locking in any decisions and yet confident that we could create a complex, rounded story given the resources we had.

Dick Block had another brainstorming activity he used at Carnegie Mellon. He told my class of sophomore design majors, “You have one million plastic yogurt container lids. What do you want to do with them?” We then spent an hour filling four large chalkboards with lists of all the things we could do. No judgments, all ideas were valid. Finally, Dick asked us what we actually could do with those lids. About one-third of the ideas, such as creating shower curtains out of them, were eliminated. Then he asked, “OK, what do you actually want to do with them?” We immediately crossed off “recycle them!” for its lack of ingenuity. Also “use them as coasters”— that didn’t sound like a lot of fun. Eventually we narrowed the list down to five options and voted on our favorite, which was filling our professors’ office with them (even though he’d wanted to cross that option off as something we couldn’t actually do; we begged to differ on that point).

I didn’t expect to be using this exercise ten years later, and yet I realized that The Duchess of Malfi team had followed a similar brainstorming process for our complex casting quandary. Three simple questions: What are we doing? Do we actually want to do it? Can we truly accomplish it? If the answer to the second or third question is “no,” it’s time to move on to a new idea.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Brilliant! Thank you for sharing your work here. I can't think of a more important issue in the theater today, especially for those of us so tired of seeing plays with "color-blind casting" (which I also believe does not exist).

For some years (decades now), I've been using something I call "racially interpretive dramaturgy" with playwrights, directors, and designers who are interested in looking deeply at the multifaceted ideas, opportunities, and issues that arise when casting a play with actors of a race, gender, ability, body-type, or age not "traditionally" cast in that role. As you demonstrate so eloquently, it's not enough to plug-in actors of Color, to put women in men's roles, etc. I believe we can only truly plumb the depths of characters and a play when we actually see, acknowledge, and incorporate the identity, culture, representation, and experiences of the actors we cast, and the ways that casting changes the shape and texture of the play.

I've endured much criticism from many people in theater over the years for these techniques, and I have rarely found directors much interested in exploring the meaning behind "non-traditional" (whose traditions?) casting. I'm often told there's "no time" to have these discussions in ever-tightening rehearsal schedules. I hope, through work like yours, students will enter the world of theater with a better understanding of the impact of their decisions in casting and creating the roles in a play, and the importance of those decisions to our culture(s), to our humanity, and to the truthfulness and quality of our work.

Thank you for your comments here. It is an eloquent way to state what I believe. I enjoyed this article and your comments on it too

Thank you for sharing your thoughtful process! I hope this will spark a lively discussion.

What of white actors playing roles of color? In my experience, in university programs specifically, actors of color are cast as white far more often than they are cast as characters of color. And certainly more often than white actors are cast in roles of color. And when actors of color are cast in roles of color, they are still often in stereotypical roles. Not what you are promoting ,of course.

Still, sometimes color conscious casting can enable companies/universities to get actors of color on stage while ignoring plays by playwrights of color. Not that this is the case at DePaul. I know you continue to produce plays of by people of color and about diverse experiences and stories. The article did prompt me to think about this. Thanks again for your smart work here.

Wonderfully presented. Thoughtful and food for thought. Wouldn't it be truly inclusive though to include other races as well instead of limiting the scope to just black and white?

Ah, yogurt lids...mixed with The Dutchess..."some times the devil [still] doth preach." I really enjoy reading your work. Thank you.