Achieving Gender Parity

Play by Play & Role by Role

This week on HowlRound, we continue the conversation on gender parity, which has been gaining momentum this year through studies, articles, forums, one-on-one discussions, and seasons and festivals focused on women. As Co-President of the Women in the Arts & Media Coalition and VP of Programming for the League of Professional Theatre Women, I have the pleasure of working with, coordinating, contributing to, and raising awareness about many of these local, national, and international efforts.—Shellen Lubin

This series explores what needs to happen right now—in this precipitous moment—in order to profoundly, permanently expand the theatrical community's views and visions of women, both onstage and in every aspect of production.

Last April, I had the good fortune to participate in a day of conversation and idea exchange in Toronto about international efforts toward gender parity in theatre. (Read a full description of the Equity in Theatre Symposium and subsequent roundtable discussion here.) One of the outcomes of this engagement was that each participant committed to do “one thing” to push gender parity forward in her/his local theatrical realm in the immediate future. The advocacy strategy that I committed to was: casting more women in university theatre productions. This is not a new goal for me. But my understanding of the potential impact of university casting practices on the long-term health of the American theatre ecology, and the varied strategies I am using to achieve it, were reinvigorated by the conversation in Toronto.

Why do we need to cast more women in university theatre productions?

I am a theatre director and also an associate professor in University of San Francisco’s Performing Arts & Social Justice program. One of the most important truths I have learned in my eight years working in higher education is that students are what they eat. In other words, the intellectual food we offer students during their theatrical education shapes their current and future appetites. If I teach Diana Son’s Stop Kiss, then a year or two later, I am likely to get cabaret applications from students who want to direct or act in Stop Kiss. This phenomenon means that university theatre educators have an enormous responsibility to expose students to a wide-range of dramatic material, and to be conscious of the structural inequities and social biases that might be encoded in the plays we teach and produce. No play is neutral. Every play generates a social world that reflects and/or reframes our social world. Every play we read, or produce has the possibility of re-inscribing, or re-inventing our social order. Casting women in college matters because every role a woman plays on a university stage is another step toward recreating our actual social world; every role allows artists and audiences to further awaken to the fact that women’s voices and experiences matter as much as men’s do.

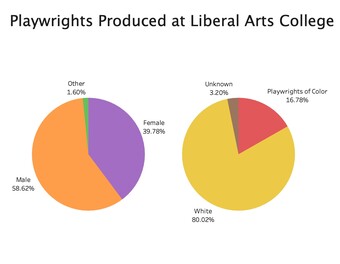

Another thing I have learned as a theatre educator is that being cast even once makes a student much more likely to choose theatre as a major or a minor, and to consider theatre as something that is for them, an activity they can imagine being part of as an artist or an audience member in the future. Our department has a good track record of putting women onstage and producing female playwrights. We’ve presented Christine Evan’s Trojan Barbie and Slow Falling Bird, Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls, Cherríe Moraga’s Heroes & Saints, and Theresa Rebeck’s Loose Knit to name a few. But despite our conscious efforts to create performance opportunities for our female students, a recent analysis of department casting practices revealed the surprising fact that male students in our program are still twice as likely to be cast as female students. That means our female students have half as many chances to discover that theatre is for them, their stories matter, and there might be room in the professional theatrical field for their creative energies and talents.

Casting women in college matters because every role a woman plays on a university stage is another step toward recreating our actual social world; every role allows artists and audiences to further awaken to the fact that women’s voices and experiences matter as much as men’s do.

How can we cast more women in university theatre productions?

There are many effective strategies for casting more women on university stages. I argue that university theatre educators need to employ all of them in order to provide a nourishing theatrical diet for female and male student artists. First, there are many wonderful resources for finding new plays written by women ranging from the We Exist list, to the Kilroys lists, to the Big Ten Theatre Consortium, to the National New Play Exchange. Next, devising is an excellent way to develop theatrical work that speaks directly to the interests of a particular campus community and offers flexible casting opportunities. At USF, we have produced both new work and original devised work that offered many strong roles for our female student actors.

But what about the dramatic canon? Shakespeare is eminently flexible, and we even have many examples of successful all-female productions of Shakespeare’s plays. Phyllida Lloyd’s recent critically acclaimed productions of Henry IV and Julius Caesar serve as inspiration in this arena. But what about Aeschylus, Jonson, Ibsen, Strindberg, Chekhov, Mamet, and Shepherd? In departments like mine, female actors outnumber male actors (sometimes three to one). How can we keep producing classic, modern, and twentieth-century plays that have more roles for men than women, and in which female characters are often overshadowed by male protagonists and majority-male ensembles?

I would argue that in order to effectively train the next generation of theatre artists, we must keep producing canonical plays on university stages as a complement to producing new and devised work; they offer students the chance to embody character and stories that have been elemental in the construction of our cultural heritage. But I also believe that we will not achieve gender parity in theatre until we rethink how we cast these plays—we must reimagine women in the dramatic canon play by play and role by role.

What does this mean? It might mean transposing some roles from male to female. It might mean casting female actors in male roles and asking them to play them as male because a role is a role—the human instrument is capable of telling stories in multiple modalities. It might mean questioning why one set of images and behaviors onstage seems more “natural” or “realistic” than another, and exploding our understanding of both gender and theatrical genres. For sure, it means recognizing that an actor who gets to experience playing Dr. Faustus or Austin in True West or Hamlet is going to be a different actor than one who doesn’t get the chance to inhabit those roles.

Our approach to gender parity in university theatre must be informed by the classic improvisational motto “Yes, and…” As university theatre educators, let’s start marrying “Yes…let’s produce The Seagull!” with “And…how can we expand our minds about casting so that we can get more women onstage in this wonderful play?”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

tots agree! I had a professor tell me that men could play women's parts but women just can't play male roles. We were doing As you like it. They were going to double cast the 8 of us women in the 4 female parts and get the 2nd year boys to play the rest of the roles. I staged a protest and got them to change the play to a Restoration comedy. It's a lack of imagination and lack of awareness of what training programs are really there for.

Love this - thanks Christine! Great to hear your voice... And you could also pick new plays by female playwrights with lots of parts for women.

Absolutely! That is one of the MOST important strategies for getting more women on university stages!

Yes!!!! And....this reflection on gender parity within theater by Christine Young is a fantastic truth telling that gives substantive guidance on how to advance the role of women in theater. Loved it!