Will Eno’s Theatrical Rhythms

Small Town-ish in a Really Good Way

For a heady period of time in the spring of 2014, playwright Will Eno had two productions running simultaneously in New York City, which inspired a 2014 Drama Desk special award for both ensembles and for the playwright. “To the Ensembles of Off-Broadway's The Open House and Broadway's The Realistic Joneses and Will Eno,” the award inscription reads, “Two Extraordinary Casts and One Impressively Inventive Playwright.” Eno recently reflected in conversation that the Drama Desk joint ensemble award was “fun and exciting and a huge surprise and felt really sort of small town-ish in a really good way.”

The Open House, which in addition to the compound 2014 Drama Desk special award also received 2014 Obie and Lucille Lortel best play honors, has now joined Eno’s other TCG-published works in a spanking new 2015 TCG edition. The clustering of recognition for this play in particular, among Eno’s growing body of produced and published work, is worth some analysis and reflection. Is this a cumulative awareness of, or a giving into, Eno’s view of the world? Did 2014 reflect a kind of final critical understanding of Eno’s subject matter? Are we all finally ready to experience with him, according to his rhythms and speech patterns, the gentle devastation of small town family life? Perhaps yes to all of the above.

Small and large tragic things happen, and small and large reactions occur as a result. Eno’s plays are not about explosions (verbal, technological) but about rifts in conversations and human lives, where the chaos stealthily seeps in.

And with his many accolades, this newly minted fifty-year-old is self-effacing and delightfully appreciative that he’s understood and his work is well received. We exchanged emails then met on the phone for an extended chat on a recent afternoon about his new publication, the unfolding of his career, and the gentle and provocative stage worlds he creates.

A New England Athlete with Day Jobs

Eno is a child of New England with a “sort of a normal background” who thought for a long time he was going to be a professional biker. Born in Lowell, Massachusetts and reared in a set of nearby towns, he went to UMass Amherst after high school (leaving just short of graduation) and was involved in bike racing seriously enough from ages twelve to twenty-two that he trained at the US Olympic Training Center in Colorado. “I think it saved me from doing all the stupid adolescent things I ended up doing in my twenties, anyway.”

Writing was something he worked on around intense day job hours. In his late twenties he worked on Wall Street “making cold calls for six bucks an hour” and would write at night, which influenced his approach.

I was usually so exhausted (the hours were from 7:30am-6:00pm, at the least) that I couldn't really maintain whatever pose of a human I had usually presented in writing, so I was able to write some new and sort of strange things, that seemed separate from me, but that still had some weird connection. I then studied fiction writing with Gordon Lish and he taught me about writing at the microscopic level and about how to carry yourself as a writer, as a human being.

A short play called An American Lies Dying on American Ice, about a hockey player who is seriously injured in the middle of a game and the time-filling response of the announcers, was an early step into his unique style and authorial voice. Small and large tragic things happen, and small and large reactions occur as a result. Eno’s plays are not about explosions (verbal, technological) but about rifts in conversations and human lives, where the chaos stealthily seeps in.

Stage Doors and Chance Encounters: London to New York and Back Again

Eno found his way onto US stages through an unsolicited script left at the National Theatre stage door in London. Whether this was 1999 or 2000 is murky in his memory. At the time he was employed as a proofreader of psychology textbooks.

I dropped Tragedy: a tragedy off at the stage door of the National. I wrote some crazy note on the first page of the script with my left hand, and I’m right handed. A month later Jack Bradley, then the literary manager at the National, called up and said: “We’d like to do a reading at the Studio and can I send it to a BBC radio producer?” Christopher Campbell, now the Literary Manager at the Royal Court, was working at the National then too. This whole great life over in London started up from that. The Gate production happened out of the reading at the National Studio.

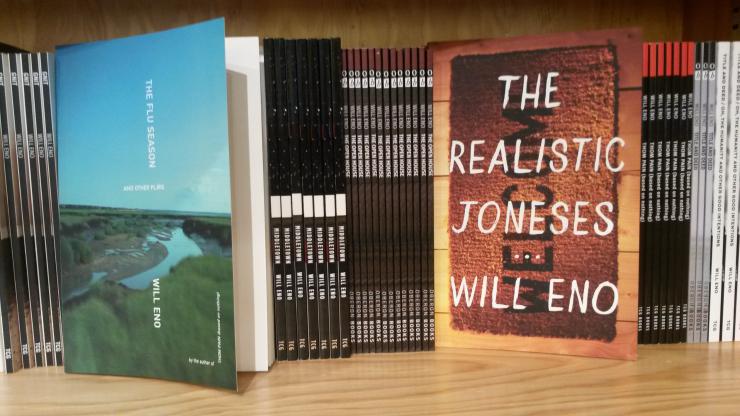

Produced at The Gate in Notting Hill in 2001, Tragedy: a tragedy is about television journalists on-air navigating a twenty-four-hour news cycle covering a sunset that may go on forever. Two years later, The Gate produced Eno’s The Flu Season about inmates and staff in a mental institution. (Both plays are published by TCG in The Flu Season and Other Plays.)

Eno’s plays have now appeared on stages in many areas of the US including: Thom Pain (based on nothing) (“stand-up existentialism” at DR2 Theatre in 2005), Middletown (a small town story of neighbors, “delicate, moving and wry amble along the collective road to nowhere,” premiering at the Vineyard Theatre in 2010), Title and Deed (“a haunting and often fiercely funny meditation on life as a state of permanent exile” in 2012, the first of Eno’s Signature Theatre Residency Five productions), The Open House (a conventional living room drama with several twists, his second Residency Five production in 2014) and The Realistic Joneses (a four-hander with suburban neighbors all named Jones, commissioned with a premiere at Yale Repertory Theatre in 2012 and produced on Broadway in 2014).

Journeys to Eno’s Work

Will Eno’s plays Thom Pain (based on nothing), a finalist for the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, and Middletown, recipient of the 2010 Horton Foote Prize for Promising New American Play, both deal with daily life’s gentle and devastating interactions. While these awards engendered national and international attention for Eno’s quirky talent, the American first found audiences in England.

British audiences were exposed to Eno first, as were the British press. Responses by The Guardian’s Lynn Gardner moved from finding a play “both potentially profound and tedious” (a 2001 production of Tragedy: a tragedy) to “smart-alec games with form and style are very witty, youthful and enormously engaging” (a 2003 production of The Flu Season) to “vicious stuff, written in a language so deceptively innocent, so full of platitudes, that you don't realize it has cut you deep until you feel the warm seep of bloody despair” (a 2004 Edinburgh Festival production to Thom Pain (based on nothing)). This journey of bafflement to quiet entrancement is replicated in a number of critical and personal interactions with Eno’s voice.

I asked him whether he found this experience common for those who see his work.

I don't know what journey people take, over the course of a couple plays. Maybe what seems willfully ambiguous, at first, starts to seem like a gift of space to think and feel, later. Something like that? I don't think it's generational. People always get worried about weekday matinees, but I sometimes think people who are a little older can laugh harder at the hard parts of life.

Someone said that the play was about evolution in this real absolute sort of dramatization of Darwinian evolution, in both its gentleness and sort of brutal indifference. Something happening gently is good by me.

Rhythms on the Page and on the Stage: Stillness and Solitude

Reviewers often comment upon the role of stillness, silence, pauses, and nonverbal moments in Eno’s work. Many reviews of his work are full of comparisons to stylistic and linguistic innovators. An enthralled Charles Isherwood reflected in his 2005 review of Thom Pain (based on nothing) on Eno’s language and tone as “jaggedly quirky, crisp and hypnotic.” In a slightly disappointed but still engaged review of Eno’s The Open House in 2014, Isherwood again underscores language and rhythms, pauses, and parsimony:

Wryly humorous and deeply engaged in the odd kinks and quirks of language and its fuzzy relationship to meaning, his plays are also infused with a haunted awareness of, and a sorrowful compassion for, the fundamental solitude of existence.

What is Eno’s sense of space around the words, pauses and stillness, and his lack of fear of silences?

I think it might come from being a sort of anxious person, with a sort of anxious background, so that there was never any such thing as stillness, really, in my childhood. A room full of still people is almost the most tense and energized thing I can imagine, and so maybe that idea, that stillness is just a different kind of motion, has made it somewhere into my plays.

The Open House: Two Sets of Characters, a Dog, and Production Notes

For some, after the monologues of Thom Pain and Title and Deed and the monotonic story beats of Middletown, an encounter with the superficially familiar structure of The Open House is a new and welcome invitation into Eno’s playwriting mind and provides a broader palette of theatrical references.

The play begins with a father, mother, son, daughter, and uncle, and an off-stage barking dog. Utilizing carefully choreographed exits, entrances, and dialogue, a new constellation of characters played by the same actors looks over the house for sale: a real estate agent, a married couple, a handyman, an interested sibling, and, delightfully, even the dog makes an appearance.

We talk about the gentle power and delicate choreography of the play’s structure and Signature production. “Someone said that the play was about evolution in this real absolute sort of dramatization of Darwinian evolution in both its gentleness and sort of brutal indifference,” Eno mused. “Something happening gently is good by me.”

And then, there was the dog Marti (provided courtesy of William Berloni Theatrical Animals) whose bouncing joyous entrance at the play’s conclusion was a delightful and audience-awe-inducing surprise. Eno recalled the childlike glee with which he and his director went to the Signature’s Artistic Director Jim Houghton at one point in the play development process. “It was like we were kids saying: can we get a dog, can we get a dog? He went for it instantly.”

Eno’s wife, actress Maria Dizzia, was about six months pregnant at the time of the production. Close friend Tracy Letts had his own interpretation of the meaning of the dog. “Tracy said when the play ended and the dog came running out, he wanted to jump up and say: that’s the baby, that’s the baby! Suddenly there’s this new life in the room.”

So was Eno working through issues with his own family in this particular story?

My dad wasn’t particularly funny but I think I got the rough tone of him. I think I captured the general quality of the great cloud that he was in that house. I’m sure I was trying to do all sorts of things, but in some ways I was trying to figure out how I felt about my family and the idea of family.

The TCG publication of The Open House includes a thoughtful and detailed production note about opening images and pacing. Some playwrights are very involved in this regard, and some very hands off about stage directions and stage moments. Eno’s tone in this note seems to be a bit of both: do what you want to do in your production and let me tell you about some little bits of stage business and prop and lighting details from the Signature production.

When Anna, played by the actress who plays Daughter, entered, this is the beginning of a profound transformation, thought it should begin slyly and quietly. That is, she should not charge in and immediately start transforming the room. In the Signature Theatre production, we used some magic battery-powered fake flowers that bloomed over the course of the last half hour of the play. I’m sure many people did not notice this, but I mention it because I think attention to little details like this, things that slowly and almost unnoticeably accumulate, so that by the end of the play the audience is looking at a different room filled with different people, can make for a very powerful experience.

Current Gigs and an Artistic Home

When asked about the things occupying him at the moment, Eno lists a range of activities:

I'm trying to finish two plays that I've been working on for a long time, and am also going into rehearsal for Thom Pain, which Rainn Wilson will be performing in Los Angeles, directed by Oliver Butler, at the Geffen. I teach here and there. My wife Maria and I have a one-year-old daughter, Albertine, and she gets the majority of our energy and attention and wonder.

He’s also about to dig into the third of three pieces for his Signature Residency Five, in which he has been guaranteed three world-premiere productions of new plays over the course of a five-year residency. “It’s on the books for 2017,” he tells me. Signature has become his artistic home base. “People talk about the artistic home, and those are really big words and I don’t know if the thing that they’re talking about really fills up those words normally. But I really think of Signature that way.”

A Parting Shot

Eno recalls a photo from opening night of The Realistic Joneses on Broadway that he suggests says something about his work. The photo is of Tracy Letts in Eno’s first Broadway play after a triumphant opening night curtain call.

It’s just the four lawn chairs and Tracy Letts in the background, exiting. I always thought it an incredibly moving picture. He’s sort of leaning to the side, and he looks so Tracy Letts-ish, somehow. The chairs look a little sad but also bright—just sort of sad and not eerie, but melancholy maybe. Tracy looks kind of happy. When people say there’s a spring in someone’s step, it looks like a photograph of the spring in someone’s step.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

love his plays!