In Defense of Late Career Playwrights

Mamet's The Penitent and McNally's Penitent

I saw The Penitent twice last month—which is to say, I saw Penitent by Terrence McNally at the Cherry Lane Theatre, and The Penitent by David Mamet at the Atlantic Theatre.

The McNally piece was one of seventy-four plays, none longer than a few minutes, commissioned by Primary Stages for a single evening entitled “Morning in America, November 9, 9 a.m.” Experienced playgoers and playmakers could reasonably assume that the seventy-four playwrights shared similar views about the election results, and that they would interpret their assignment both literally (November 9 being the morning after Election Day) and ironically (“Morning in America” was Ronald Reagan’s campaign slogan). One of the plays that met both expectations, in a memorable way, was by Matthew Capodicasa, given a title made up of punctuation—[…]—and consisting of an actor who just kept looking at his smart phone and saying “F…!”

Several plays pictured a character stuck in a nightmare, such as Kat Ramsburg’s How To Get Out of Bed When You’re Out Of Xanax. Bekah Brunstetter’s Meryl’s Apology beat Jimmy Kimmel’s “overrated Streep” riffs at the Oscars by a week. However likeminded their politics, the playwrights were theatre artists, not manifestly polemicists, and so there was a range of tones and subjects. Jonathan Tolins, performing his own play, Make My Colon Great Again, gave an amusing account of his discovery that the surgeon he had selected to perform a major operation on him was a Trump supporter; after some (hilarious) indecision, it ultimately didn’t change his mind about her competence. In Topher Payne’s more serious All Apologies, a Trump supporter said he was going to stop apologizing for being white and being Christian and being from a rural area: “We’re not sorry anymore.” Thanks to Payne’s words, and the actor portraying the character, All Apologies came off not as chilling or repellent but as insightful.

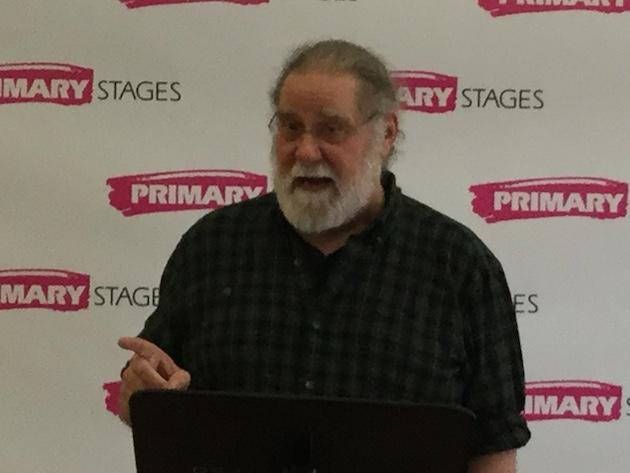

The penitent in McNally’s play, read by Richard Masur, was asking his priest for forgiveness because he voted for Trump. There was a suggestion in the text that the character is a racist, but McNally deliberately complicates the picture; the character tells us he voted for Obama.

It is safe to say that Penitent is not McNally’s best work. But I’ll go further—I haven’t cared for the work he’s done in the past decade: Mothers and Sons; The Visit; the updated It’s Only A Play—as much as the plays and musicals earlier in his career—Master Class; Love! Valour! Compassion!; Ragtime; Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune. What I hope is that McNally, now seventy-seven years old, doesn’t care what I think, and keeps on writing and getting produced—which he seems to be doing: He wrote the book for the musical Anastasia, set to open on Broadway in April.

Both Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller—even better established as great dramatists—wrote their most popular plays when in their thirties, and almost all their familiar plays by the age of fifty.

Mamet’s The Penitent, which is on stage at the Atlantic through March 24, is a full-length play, but a short one—eight two-character scenes, and a running time under ninety minutes, which includes an unnecessary intermission. Chris Bauer portrays Charles, a psychiatrist whose patient has gone on a killing spree. Citing his oath of confidentiality, Charles refuses to talk to the press about “the boy” (as the killer is called by all the characters), and refuses as well to testify on his behalf. Somehow, Charles becomes a victim of the press, of the legal establishment, and of the medical establishment, which begins the process of taking away his license. I say “somehow,” because I didn’t understand the cause-and-effect. Too much of The Penitent’s plot struck me as muddled. What seemed clear is that Mamet is using the play to make cynical observations about these American institutions, and also to explore the contrasting obligations of professional ethics and religious morality. (After the trauma of the killings, Charles has returned to the piety of his childhood.)

It is safe to say that The Penitent is not Mamet’s best work. But I’ll go further: I haven’t cared for the work he’s done in the past decade—Oleanna, Race, The Anarchist, and China Doll—as much as the plays and movies earlier in his career—American Buffalo, Glengarry Glen Ross (which won the Pulitzer Prize in Drama), Speed-The-Plow, A Life in the Theater; the movies for which he wrote the screenplays, The Untouchables and The Verdict.

The difference between McNally and Mamet is the pile-on. The Old Neighborhood was the last new Broadway play of Mamet’s that received widespread acclaim; it opened in 1997. The reviews for his subsequent work seem to have gotten progressively worst.

Until then, critics were placing Mamet “in the pantheon” of the twentieth century’s “great dramatists.” Some attribute the change to Mamet’s much-publicized “conversion” from liberal to conservative. Those who believe this on the political left imply his politics have clouded his dramatic judgment. Those who believe this on the political right say his politics have clouded the judgment toward his work of the critics and left-leaning playgoers.

It’s hard for me to accept either of these as the whole picture when I consider his play November, a political satire that opened on Broadway in January 2008, a couple of months before he wrote the article in the Village Voice, “Why I Am No Longer A Brain-Dead Liberal.”

In November, Nathan Lane portrayed an unpopular president who was desperately scrambling to avoid losing a second term. Act II begins with his aide saying:

“We can’t build the fence to keep out the illegal immigrants.”

“Why not?” the president whines.

“You need the illegal immigrants to build the fence.”

Keep in mind this was in 2008, during the administration of George W. Bush. Is this conservatism in the Age of Trump?

Mamet himself has implicitly acknowledged the decline of his work, and implied it’s due to his age. “Playwriting is a young man’s and, of late, a young woman’s game,” he said in 2005, when he was fifty-seven. (He turns seventy this year.) “Most playwrights’ best work is probably their earliest.” This may or may not be true, but it’s not the whole story. Both Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller—even better established as great dramatists—wrote their most popular plays when in their thirties, and almost all their familiar plays by the age of fifty. But they both kept on writing for the rest of their lives, producing works over decades to which many contemporary critics reacted dismissively. Since their deaths, a new generation now defends Miller’s and especially Williams’ later work, fighting to reverse a consensus they see as unfair and inaccurate.

To my mind, then, the authors of Penitent and The Penitent have nothing for which they need do penance. They should just keep writing.

***

Jonathan Mandell’s Newcrit piece usually appears the first Thursday of each month. See his previous pieces here.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Small correction: Mamet wrote Speed-the-Plow; Speed-the-Play is a one-act parody of Mamet tropes by David Ives.

That was a typo, soon to be corrected (I hope), but it's fascinating to learn that Ives wrote a parody of Mamet. Did you see it performed?

I did. A company I was with did the complete set of Ives's expanded 'All in the Timing' collection back in 2000. Our audience didn't know much Mamet, so it didn't pop.

The typo is fixed!

Yes, but the question remains, how is it that white men are more likely to get their works produced then white women and even men and women of color? Can you explain those disparities?

Tim, I'm not sure why that's "the question" in an article about late-career playwrights. But, ok, some thoughts:

I think it's much fairer to ask something in the aggregate , as you just did -- or to ask "Why is David Mamet produced more than, say, Caryl Churchill" (if that's true) -- than to ask "why is Mamet's work produced when so many women playwrights are not?" One cannot pretend that a specific playwright's fame -- and thus following -- is not a factor in the choice to produce their work.

The success of New York's Signature Theatre, for example, is built on the idea of theatergoers' lasting curiosity about playwrights whose work they've already seen.

On the micro level, there's evidence that this is starting to work to the advantage of already-established playwrights who are women and/or people of color.

Here's a list by American Theatre Magazine of the Top 10 most produced playwrights of 2016-2017 (keeping in mind that this is drawn only from the pool of 411 member theaters of Theatre Communications Group)

August Wilson

Lauren Gunderson

Arthur Miller

Ayad Akhtar

Tennessee Williams

Robert Askins

Annie Baker

Quiara Alegría Hudes:

Ken Ludwig

Tony Kushner

Yes, Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams are in there -- but so are August Wilson and Annie Baker.

I see, but should theatres challenge audiences to see more work that challenge the disparities in your opinion or should they accommodate to audiences?

I don't run a theater. Those who do typically say that it's a balancing act.

To get back to specifics: Let's keep in mind that David Mamet co-founded the Atlantic Theater Company, where his latest play is being presented; it would be odd indeed to expect the theater he founded to shun his work. On the other hand, this season the Atlantic also produced "Tell Hector I Love Him," written by Paola Lazaro, a 28-year-old woman born and raised in Puerto Rico.

And I'll wade deeper into the complexities of this debate over disparities, as you call it, to point out that it was the Atlantic that premiered "Between Riverside and Crazy," the Pulitzer Prize winning play populated largely by characters (and performers) of color, and written by Stephen Adly Giurgis, a middle aged (presumably straight and able-bodied) white man.

So, outside of dropping this one theatre company, which I am sure has their reasons for including more narratives than the usual white male narrative, how is that oppressing the white male voice again?

I'm sorry, I don't quite follow what you're saying, nor its connection to my essay. (Or have we left that far behind?)

You wrote this essay to defend the right to produce Mamet plays in this day and age, and if you don't quite follow what I am asking, then, I wonder why you wrote the essay.

I literally didn't, and don't, understand your comment. Having now read it several more times, I'm going to assume that your line "oppressing the white male voice again" is sarcastic, but I don't understand where in my article I make any claim that anybody is "oppressing the white male voice" or even trying to. Please show me the line where I say anything even anywhere close to that.

And my essay is defending the right for Mamet to continue to WRITE his plays, and perhaps the right of theater people to continue to respect the body of his work.

As long as I'm writing another comment, I'd like to add something that I did not mention in the piece. There is some evidence that it is simply incorrect that playwrights lose their power as they get older -- the best example is that of Eugene O'Neill , whose most popular and most critically admired play, Long Day's Journey Into Night, was written late in his life, and both published and produced posthumously.

Actually, I wasn't being sarcastic about "oppressing the white male voice," I was being serious. I just wanted to know why defending Mamet and his body of work is more important than respecting Caryl Churchill or Eve Ensler? The tone of your essay, from my interpretation, presented itself as an opposing argument to a Howlround article about how Mamet and LaBute shouldn't be put on much anymore because of their racism and sexism. I responded with questions because I wanted to have an intellectual discussion with challenging questions as means to continue having the discussion from the previous article. To add to that, I was wondering why Mamet needs defense of people who look like him when he can defend himself, and why is it that the same defense cannot be applied to Eve Ensler and Caryl Churchill? Could it be that there is a gender parity in theatre? Could it be that there are still sexist double standards in viewing and debating theatre? I mean, the words "white," "male," and "oppression" are words people know, but together, it seems to be a recipe for cognitive dissonance. What is the harm in recognizing fault of an established playwright? Why is it so important to defend the status quo when theatre like the world is changing and maybe Mamet and LaBute are not as relevant as they were when they were in their heyday? Why is it so important to you that Mamet continue writing? Why is it important that his plays be, regardless of individual feeling? Mamet is more likely to get produced these days than Ensler, thus the gender parity.

I write a monthly piece (usually the first Thursday of the month) for Howlround's "NewCrit" section, which is intended to focus on a single work or group of works currently or recently on stage in (in my case) New York. I thought it was sort of interesting that these two playwrights of the same generation had written two plays with the same title that were staged at the same time in New York.

You're reading a whole lot into the resulting piece that is simply not there. (for example, "LaBute.")

If you scroll through the index of my previous NewCrit pieces, you'll see I have written about pioneering Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector; Muslim-born playwright and performer Nadia Parvez Manzoo; African-American theater artist Anna Deavere Smith, and so on. I would be delighted to write a piece about Caryl Churchill, whose work I greatly admire -- and indeed I have written about Caryl Churchill elsewhere, even mentioned her in HowlRound essays (e.g. "Caryll Churchill’s Love and Information is a triumph of stagecraft.") I would also love to write about Eve Ensler, who is indeed often unfairly under attack.

If you want to continue having the discussion from the previous article about Mamet, why not have it there?

But I am curious about one of your points: Are you saying that even Mamet's earlier work, such as American Buffalo, Speed-the-Plow, and Glengarry Glen Ross, is so suffused with sexism on the part of the playwright that none should be produced anywhere anymore?

Hi, sorry it has taken a while for me to respond to you. The life of a thespian is never not busy.

To answer your first question, I consider Howlround's articles to be continuing discussions anyway, as it is a good place for discussions and discussion-starters. Maybe my fallacy of logic was thinking this article was a response piece and not an individual one.

Regarding your second question, I think outside of the luxury of period pieces, those plays you mentioned don't really serve a purpose today except as period pieces.

Define "serve a purpose." Steppenwolf put on a fantastic revival of American Buffalo in 2009. I can personally vouch for the fact that many in the audience found that it "served a purpose," as does all great theatre that poses difficult and complex questions without offering easy solutions.

I don't really get your comment. If there are people who support Mamet's work and find that it continues to be relevant, why shouldn't they speak out in support of him, regardless of their ethnicity or skin color? And, it's not a zero sum game -- producing Mamet does not mean the theatre cannot produce Eve Ensler and Caryl Churchill -- you're presenting a false choice.

Why is "oppressing the while male voice" your goal? Why should good white male playwrights not get their plays produced? Because you want to punish them for the inequities of the past?

As I mentioned in another comment recently, I also much prefer Mamet's early work. But I don't think his decline is due either to age or politics, but to something which I fortunately (since I came to playwriting late) don't seem to have to worry about: Unbridled Success!

(Which, as all devout Seinfeld viewers know, was also the downfall of Billy Mumphrey.)

:)

Kindly elaborate. Why would success cause him to become more....I guess...abstract and philosophical?

While doing my every-other-day constitutional (read: walk) it popped into my head that it was actually "Unbridled Enthusiasm" (not success) that was alleged to be Billy Mumphrey's downfall. So much for my attempt at humor.

In any case, my comment was intended to be light-hearted, referencing what many others throughout history have observed: that success often changes how writers (and people in general) look at things.

But if I were asked to elaborate (and I was) In particular, it seems that financial success leads to a more conservative attitude towards things. Presumably because one's subconscious says "hey, I'm doing pretty well under the current system, so don't rock the boat!".

Whereas when one is a starving artist (whether literally or figuratively), it makes intiuitive sense to question the system, to examine whether the lack of one's success (and that of others one cares about) is due not so much to oneself, but to flaws inherent in the system.

This makes sense to me. It doesn't completely explain the major way Mamet's work has changed over the last few years, though. Much of his work lately is kind of ....incoherent.