American Sign Language in Theatre and Its Impact or, Why We Need More Deaf Actors Onstage

This week on HowlRound, we're discussing Deaf theatre. This series is a result of the NEA Roundtable on "Opportunities for Deaf Theatre Artists" hosted by the Lark Play Development Center in New York City on January 20, 2016.

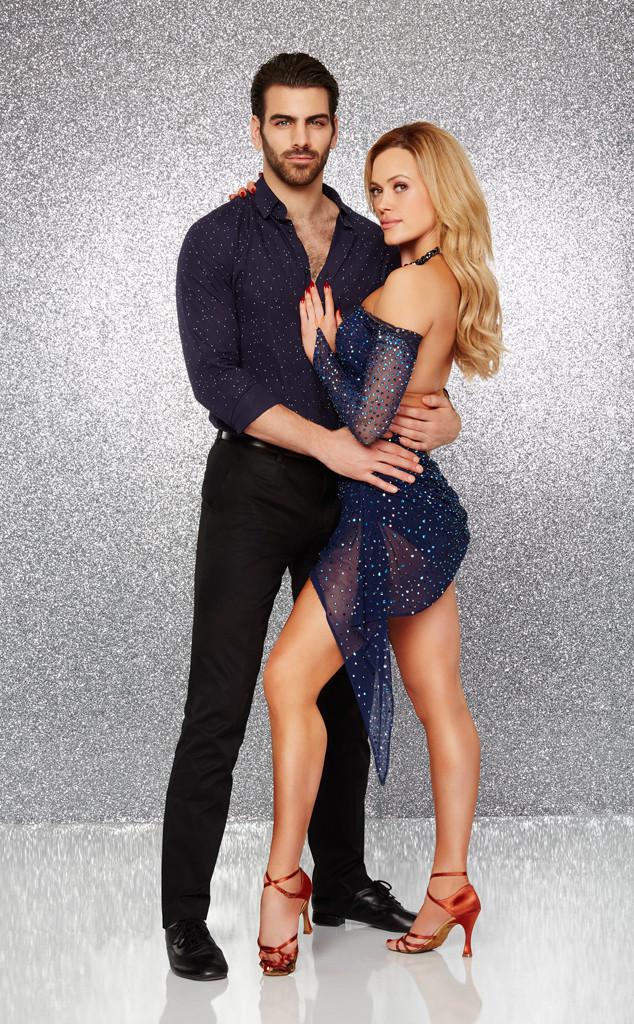

“Nyle DiMarco… [has] such beautiful expression… I was thinking about how incredible he is as I was drinking my coffee this morning, and realized that sign language is a kind of a dance—it is a movement that expresses. So in a way, he’s been dancing with his hands his whole life. I think this is part of why his performances are so deeply moving. When he dances, there is a hush that comes over the ballroom that is not just about the respect we all feel for the fact that he is dancing without actually hearing the music, but is also about being in awe of his powerful connection to the movement, his heartfelt storytelling.”—Carrie Ann Inaba, Access Hollywood

DiMarco, a Deaf contestant on this season of Dancing with the Stars and the winner of the recent season of America’s Top Model, has embraced the novelty of being a Deaf dancer, labeling his team #RedefiningDance. A Deaf person dancing along to the beat is clickbait to the uninitiated public. To the Deaf community and to the people familiar with it, Deaf people have been dancing and performing for as long as we remember.

The history of ASL theatre is young. With any luck, it will arc upwards. I hope that in the near future Deaf actors will get so much work and perform themselves into oblivion so we can let go of the meanings associated with Deaf characters on stage and the obligation to be spokespersons for a greater cause.

Inaba’s eloquent and thoughtful assessment of DiMarco came to my attention on my Facebook feed highlighting an obligation, though not always fulfilled, of the Deaf performer to become a spokesperson for their community as they enter the public arena. The actions and statements of these individuals are carefully scrutinized by our community: we understand these days, that our social and political standing as a community depends in large part upon representations of deaf people in the media. In this regard, DiMarco hits the trifecta: he wins fans over with each thrust of the hip while advancing knowledge and understanding about our community and our native language, American Sign Language (ASL).

“The long history of the language is delivered to the performance, and in the performing, it is made anew.”—Carol Padden and Tom Humphries, Inside Deaf Culture

The history of Deaf performance in America is inextricably bound with ASL, which jumped German in the ranks last year to become the third most-taught foreign language in schools. The classification of the language as foreign belies its status as the one true American language.

ASL came into being when the various sign systems that had emerged among interactions of Deaf people in colonial towns were brought together by the founding of the first Deaf school in America in Hartford, Connecticut in the early part of the 19th Century. The desire to communicate is the primal spark that drives us to sign language—we seek to bring ourselves out of the darkness that is imposed upon us by the people around us: the hearing parents, caregivers, and teachers whose first instincts are to mold us into their own image. Since the beginning of history, many Deaf people have individually and collectively arrived at the conclusion that we are a visual people that prefer a visual language.

“What matters deafness of the ear, when the mind hears? The one true deafness, the incurable deafness, is that of the mind.”—Victor Hugo

The act of embracing ASL may be interpreted as a retreat from society. The opposite is true: we turn to ASL so that we may communicate with the world. We just don’t see another viable option. Theatre, film, and performance have become essential means of expression and a key driver of standing for our community.

The genealogy of American Deaf theatre can be traced to the inaccessibility of mainstream theatre to Deaf audiences. That is not to say Deaf people weren’t physically able to go to the theatre in the old days: instead of experiencing the performances like hearing audiences, they would rely on hearing companions to summarize the action or attempt to decipher the plots through visual cues, blocking, and body language. It was not until the early 1980s that the Mark Taper Forum, spurred by its own success with the Broadway-bound play Children of a Lesser God (1979), would offer the first regularly-scheduled ASL-interpreted performances of theatre in the nation.

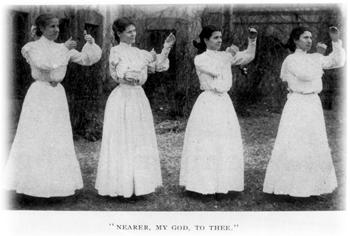

Keen to understand the inaccessible cultural world of books, art, and performance around them, Deaf people founded literary societies in the late 19th century. These aspirational individuals sought to exude sophistication while proving that they could be connoisseurs of the arts and letters in a world of English speakers. In those societies, Deaf people translated existing plays into ASL and performed for all-Deaf audiences.

After the Milan Conference in 1880, which banned ASL from schools for the Deaf and essentially banished the Deaf community from their traditional gathering places, the community went into exile into the warren-like corridors and meeting rooms of Deaf clubs. In those spaces, the currency was knowledge. Deaf people would gather to gossip and to share tips about the inaccessible world around them. The passing along of life knowledge and skills was a major component of activity in these clubs. The clubs buttressed their standing against competing clubs by hosting athletic competitions, storytelling sessions, and theatrical performances. Performers and theatrical actors in these clubs quickly realized they could use dramatic license to push the boundaries of ASL and maximize its spatial and temporal qualities. As a result, the language as a whole grew more versatile and came to incorporate cinema-like techniques.

"While it is able to ascend to the most abstract propositions, to the most generalized reflection of reality, it can also simultaneously evoke a concreteness, a vividness, a realness, an aliveness, that spoken languages, if they ever had, have long since abandoned.”—Oliver Sacks, Seeing Voices

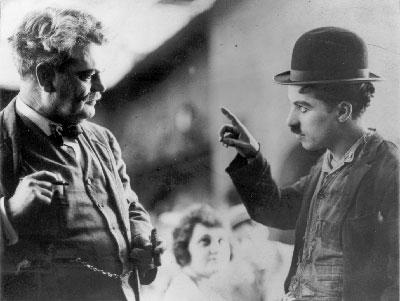

Emboldened by their artistry, Deaf actors that had honed their performance skills in the clubs, like Granville Redmond and Albert Ballin, tried to break into Hollywood, knowing that they were skilled at the body language and mugging that were necessary talents for work in silent movies. Charlie Chaplin, for example, befriended Redmond out of self-interest: he cribbed acting techniques from the Deaf performer while pigeonholing him to insubstantial roles in his movies.

When the talkies arrived, Deaf performers knew their employment prospects were next to nil. Coming back to the Deaf club without having had made it in Hollywood must have been a humbling experience for these actors. Those who remained undiminished by this failure went back to performing vaudeville skits and signed stories in addition to silent films made expressly for the Deaf community. By this time, performance had become a mainstay of the Deaf club circuit. Among the most successful of the impresarios driving this scene was Wolf Bragg, a storyteller and performer who was remarkably adept at producing and directing plays in the Deaf clubs of New York City.

The Deaf actors in these community plays held day jobs. Performing in front of a Deaf audience must have been a thrilling outlet for these plumbers, seamstresses, and printing operators. Breaking out into the mainstream was not in the realm of possibility for them: the work was the reward.

Bragg’s son, Bernard Bragg, went into performance against his father’s wishes and became the first breakout Deaf performer. He worked as a mime and nightclub performer in San Francisco in the 1960s before touring internationally. His acclaim provided part of the impetus for the founding of the National Theatre of the Deaf (NTD), the first professional theatre of the Deaf, in the later part of the decade.

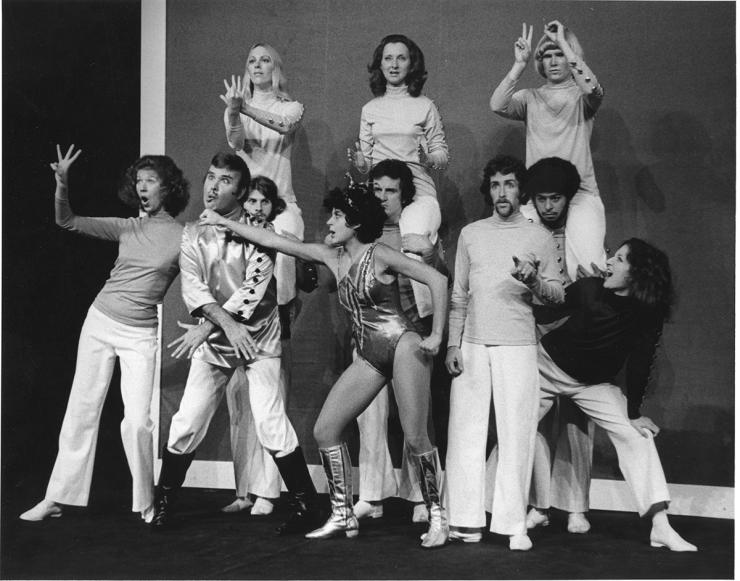

“Being Deaf in a world of sound is like living in a foreign country blindly following the cultural rules, customs and behaviors without ever questioning them”—Christine Sun Kim

David Hays, a hearing set-designer-turned-producer, was the first artistic director of NTD. He understood that the theatre’s success depended on its ability to appeal to the larger public and hired hearing professional actors who would voice for the ASL that unfolded before the audience. This was hardly an innovation, but a new sheen came across the whole enterprise. ASL became palatable to the masses. Its acclaimed directors (Arthur Penn, Joe Layton, Joe Chaikin, Peter Brook, and Gene Lasko among them) added dance-like flourishes and movements to the ASL on their stages. The political and social impact of NTD was undeniable as they dazzled audiences nationwide. For the first time, Deaf actors were getting paid on a regular basis to ply their craft.

It was around this time that NTD was bridging the gap between hearing and Deaf audience members that the Deaf community began the journey from the private to the public. Academic journals heralded the discovery that ASL was a full-fledged language with its own grammar and rules. Anti-discrimination laws were passed. The community began a decades-long transition from the walled institutions of the Deaf and the interiors of Deaf clubs to Deaf nights at Starbucks during the aughts and eventually, the Facebook and Instagram vlogs that have become part of our daily consumption (mine, at least).

The emerging success of NTD was met with resistance, however: The Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing attempted to block a primetime television performance by NTD on the NBC show Experiment in Television in 1967 from airing, threatening “unfavorable reaction from educators and parents and the informed public.” The struggle between pathology and Deaf culture had spilled over into the mainstream.

The move of ASL theatre into the public sphere essentially marked the beginning of a slow death of theatre in Deaf clubs. NTD drew from the ranks of the best actors that the community had to offer and cut off the talent supply to the clubs as they poached Gallaudet College graduates to nourish its ranks. Performances in Deaf clubs gave way to card games and captioned movies shown on 8mm projectors. Today only a fraction of these Deaf clubs exist. Deaf community theatre has undergone a similar downsizing. Versatility and mobility correlate with success within the Deaf circuit: stand up comedians, ASL poets and storytellers, variety acts, and signed music performers dominate the entertainment lineups of Deaf events today.

“One can have or imagine disembodied speech, but one cannot have disembodied Sign. The body and soul of the signer, his unique human identity, are continuously expressed in the act of signing."—Oliver Sacks, Seeing Voices

Deaf actors are drawn to theatre that bridges Deaf and hearing audiences because they want to work their craft. They also realize, perhaps subconsciously, that appearing on stage is the repudiation of the advice that their hearing parents were given when their child was born, that they were deficient and needed to be fixed. Appearing on stage and signing in front of a paying audience is the personal affirmation of the Deaf identity over pathology.

These days, activism and ASL theatre go hand-in-hand. Marlee Matlin, already an outspoken advocate for a multitude of Deaf causes, used her starring role in our company’s recent Broadway run of Deaf West Theatre’s Spring Awakening to push for greater accessibility on Broadway. Sandra Mae Frank, another actress in the production, pushed for authenticity in casting Deaf roles in a Washington Post op-ed. Our company was invited to perform at the White House in a three-hour event, “Americans with Disabilities and the Arts: A Celebration of Diversity and Inclusion” that highlighted the need for more artistic expression by people with disabilities. Our production featured Ali Stroker, the first performer in a wheelchair to appear on Broadway, and inspired a profusion of media coverage that broached the state of inclusion in our industry.

“When the encore came around, Spring Awakening, in keeping with its cultural moment but also outside of it, compelled many of us to do something that almost never happens in a mainstream space: forego clapping, together, and instead wave our hands in the air, expressing our admiration in entirely visual terms.”—Rachel Kolb, The Atlantic

As a member of the Deaf community, I have a vested interest in the success of Deaf actors, knowing that their rise is intertwined with the standing of our community. As a producer and artistic director, I am committed to finding and creating more work for our actors. The recent roundtable on Opportunities for Deaf Theatre Artists underscored the need for more opportunities for our Deaf actors, especially actors of color, to hone their craft in the very language that has come to define our existence. There needs to be a real infrastructure for them to create, devise, and grow in this country.

The history of ASL theatre is young. With any luck, it will arc upwards. I hope that in the near future Deaf actors will get so much work and perform themselves into oblivion so we can let go of the meanings associated with Deaf characters on stage and the obligation to be spokespersons for a greater cause. So we can arrive at the precise moment that the presence of the Deaf actor on stage ceases to be rationalized away with intellectually convenient tropes and only the work is critiqued. I will give good money to the person that promises to expunge the phrase “…in spite of…” from all future reviews of Deaf West plays.

Just last week, nearly fifty years after their missive to NBC, the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and the Hard of the Hearing posted an unpublished Letter to the Editor in response to a glowing piece on DiMarco in the Washington Post, calling him a political activist among other things. He must be doing something right.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Everything new and unconventional has to fight for recognition and acceptance. It always was this way. History of deaf culture and ASL only proves it. Sign language resembles dance of hands and is theatrical performance in its own right, especially when talented artist is on stage. But real dunce performed by deaf dancer is something entirely different. Seems impossible and yet it happened. Resent success of Deaf West Theater here in LA and on Broadway proves everything is possible when artists are inspired with something larger than themselves, deaf or not. Growing popularity of sign language paves the way to more success and recognition of deaf culture author is hoping for. And while I understand why Artistic Director of Deaf West Theater is willing to “ give good money to the person that promises to expunge the phrase “…in spite of…” from all future reviews of Deaf West plays”, I think we, audience, want to experience something “in spite of” rather than “because”. This is exactly why we go to the theater.

A stimulating, informative and powerfully written article. There's definitely a book there, waiting to come out.

I’ve learned so much about the deaf community from this article. I do not have any friends or family who are deaf so this is all new to me. I never really thought about sign language being the “one true American language.” I never knew that there has always been deaf performers and dancers. I was also under the misconception that deaf people couldn’t dance until I watched Nyle dance with my own eyes. It was astounding! I dance in my spare time and I cannot imagine how I would dance if I couldn’t hear the music. I also never considered how visually pleasing and interesting sign language is. It really is perfect for theatre. I would love to see a deaf performance with or without subtitles. How can I support deaf theatre?

I will echo what many have been saying. This series has been incredibly informative and a real treat to read! I can't wait to read the rest of the pieces in the series.

As far as Latin@ theatre goes, Mercedes Floresislas is doing some really important work in writing roles for Deaf Latin@ actors (and Deaf actors in general). You can read more about her work here - http://50playwrights.org/20...

As a playwright who has written three plays dealing with Deaf culture, I applaud this excellent series on Deaf Theatre. The three plays that comprise my WARE TRILOGY: MOTHER HICKS, THE TASTE OF SUNRISE and THE EDGE OF PEACE, all feature a Deaf protagonist and other Deaf characters and I do not permit them to be performed without Deaf actors in those roles. I have been deeply moved and gratified by the generosity of the Deaf actors who have graced these plays with their talent and the beauty of their expression. As a hearing playwright, I know that I might write the exterior of these character, but only the Deaf performer knows their soul! So congratulations to HowlRound for this informative and important series!

I need your sources!! Doing research on deaf theater in the 19th century. Please share your bibliography!!

Adding some love to R+J: The Vineyard in Chicago as well.

https://redtheater.org/rj-i...