We Work Hard For No Money

Findings From an Independent Survey on Theatre Internships

What do you do with a BFA in theatre? If you’re an actor, you start auditioning. If you want to work at a theatre company, you get an internship. I had two internships during and immediately after graduate school. Both were unpaid and part-time. From learning valuable skills, to observing life in fancy institutions, to meeting peers and mentors who I am so grateful to consider my colleagues and friends today, my internships were a resounding success.

However, I wasn’t able to pursue any internship opportunities until I was twenty-eight years old and had a savings account and a flexible day job that would allow me to spend many business hours each week working elsewhere for free. I still feel like I’m making up for a deficit in my career progression, yet the wait and the subsequent return was worth it. I’ve been employed in freelance capacities at one of the companies ever since, and I recently took a staff position there in a different department that will give me an important new skill set instrumental to my goal of becoming an artistic director.

There has been increased chatter lately about the unpaid internship and all of its presumed advantage-taking, including high-profile lawsuits that have exposed companies’ suspicious labor practices.

My rosy experience laboring for free is not necessarily normal. There has been increased chatter lately about the unpaid internship and all of its presumed advantage-taking, including high-profile lawsuits that have exposed companies’ suspicious labor practices. For example, in 2011’s Glatt v. Fox Searchlight, unpaid interns on the movie Black Swan sued and won, with the judge ruling that they should have been treated like paid employees based on the work they were doing. There is a discrepancy in the not-for-profit world, however. Unpaid labor is technically permissible, as long as the individual is considered a volunteer. By definition here, volunteers can’t displace a paid position, and internships must be for the benefit of the intern rather than the benefit of the company.

It’s crucial that this conversation is happening in our industry, as the internship experience is such a customary part of a young artist or administrator’s career track. I was recently involved in a heated Facebook conversation about a particular full-time, unpaid opportunity at a theatre, where commenters called shenanigans on what they viewed as a manipulation of a young person’s time and resources. This got me thinking about my own experiences and how they compare with others in the industry.

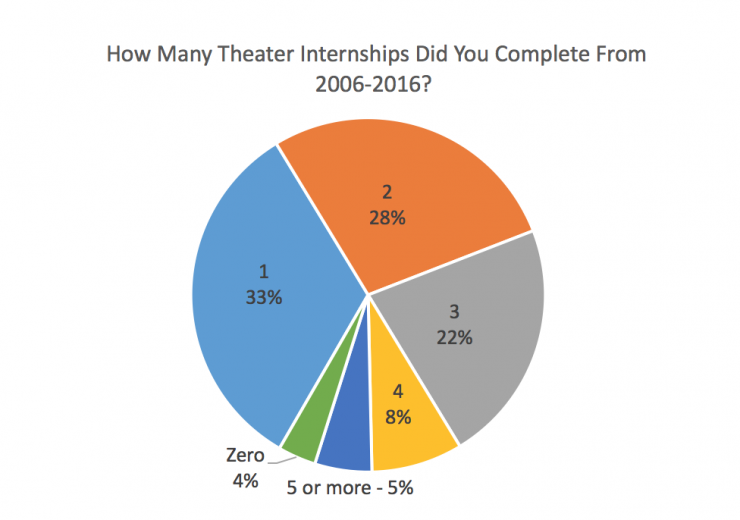

So I did what any curious dramaturg with an affinity for data would do: I created an unscientific survey about internships completed from 2006–2016, and spread the net far and wide to get a broad sampling of responses. Many people participated—most of them strangers—with 290 individuals generously answering my questions. The survey was open to all theatre professionals with no location stipulation, but the data is almost entirely United States-based. I did not control for internships outside of the United States because there were so few mentioned.

Here is what I learned: In total, ninety-five of the respondents completed one internship; eighty completed two; sixty-four completed three; twenty-four completed four; and fifteen completed five or more. Ten respondents completed zero internships, and a few people did not answer this question for reasons unknown. After sifting through the information, I reached out to some of the folks who had completed paid internships to delve a little deeper into their experiences: I received an additional sixty responses to those follow-up questions.

The survey made a distinction between internships and residencies/fellowships. Respondents were asked to classify if an experience was an internship, a fellowship, or a residency based on the language that the theatre company used when describing the position. For the purposes of this article, we are looking specifically at the internship experience, which is a lot more common and often more thankless. From the data returned, I learned that 95 percent of respondents completed at least one internship and 31 percent of respondents completed at least one residency or fellowship. That means that almost all of those residents and fellows were also interns at one time.

A ‘paid’ internship is not the same thing as a living wage.

Seventy-five percent of respondents said the work they did as an intern was valuable in preparing them to work professionally. When asked if they would generally recommend the internship experience to theatre students and emerging theatre professionals, only 62 percent said yes. There were many qualifications to these answers.

“It depends on the internship. If it's working directly with great people, then yes. But don't expect a job at the end of it.”

“If the goal is to work for a theatre company as an administrator (not as an artist) then yes. Otherwise, no.”

“As an intern, it needs to be all about what you can learn from the people you want to work with. Any hint of serving as someone's PA, or ‘paying your dues’ and you should turn the other way.”

“Only if they can afford it. A ‘paid’ internship is not the same thing as a living wage.”

This is an important point: “paid” is a relative term in the world of internships, and can mean an hourly rate, a weekly stipend, or a single check at the end of employment, although based on new regulations, the hourly rate may become the standard.

So what happens to the stats when the internships are paid? Sixty-two percent of respondents had completed at least one paid internship. I asked them if their compensation was enough to live on. Of the sixty respondents to my additional queries, 30 percent said the pay was indeed enough to live on. However, 97 percent of those paid internships also provided their interns with housing. Only two respondents who said the pay was enough were not provided with housing—one internship was in the Midwest and another was in the Southwest.

Those whose paid internships did not sufficiently cover their monthly expenses made ends meet in a variety of ways: by living with family, sleeping on friends’ couches, getting part-time jobs when time allowed, using savings, and receiving assistance from family. A handful signed up for food stamps, and some of the theatres even suggested this to the interns as a viable solution. It strikes me as ironic that federal arts funding in the United States is minimal compared with other leading nations, yet through other furtive methods the government winds up subsidizing artists anyway. But that’s another conversation.

For obvious reasons a paid internship is preferable to an unpaid internship. There is a satisfaction that comes from receiving payment for services rendered, even when that payment isn’t particularly high. To offer your services for free can feel demoralizing, especially when your work is clearly valuable and appreciated.

Still, there is a caveat to the paid internship. For those in major city centers without family support nearby, a paid internship can be as much of a burden as an unpaid internship. This is because in many cases, the time commitment of a paid internship prevents interns from taking on another job to supplement their income stream. Of the respondents providing additional information about their paid internships, 80 percent of their positions were full-time. The hours were often far beyond a standard forty-hour work week, though this seemed to be more frequent in regional theatres where housing was provided to interns who were not local to the area. As one respondent noted, “The work value was phenomenal, but they owned 100 percent of my time outside of my nine-to-five office hours, including weekends, doing ‘company management and facilities’ work.”

For all of the struggle, one hopes that eventually the interning days end and full-time employment becomes the reward. I wondered about the perception of internships as an advantage when it comes to future employment. Regarding the current state of the 290 respondents’ careers: 23 percent currently work at a theatre company in a full-time position; 15 percent work at a theatre company in a part time position; 22 percent freelance at various theatre companies so they are often employed at theatre companies for short stints though not consistently; and 29 percent do not currently work at a theatre company. When asked if they expect to work in the theatre industry for the majority of their careers, 78 percent of respondents said yes.

I was particularly struck by how many people felt impassioned by the topic itself. Many sent follow-up thoughts and commented about their personal experiences. Carving a career path in the theatre industry can be precarious, as competition is high and so is the level of talent in the field. And regardless of how hard one pushes for opportunities, there are very real socioeconomic barriers that keep those with fewer resources at a distance. Participating in the arts has always been a privilege granted to those able to do so, but it’s disheartening that so little has changed on that front. I hope that by shining a light on how we prepare our next generations of theatre professionals we also acknowledge just how uneven the playing field remains. But that’s yet another conversation for another time.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

So glad to finally read this, Molly. Was very happy to participate in your survey, and would be more than so in sharing my thoughts in greater detail. It's such a dynamic and crucial conversation that we all need to be having as professionals in the arts.

Thanks Casey! It was enlightening, and I hope the conversation continues.

I'm really glad you wrote this. It's so important to acknowledge everyone that gets left behind when unpaid/poorly paid internships become a major entryway to a career. Considering the theatre industry is always trying to expand its audience to include underserved communities it is troubling that people in those communities would have such a difficult time joining the very industry that seeks to serve them. It leaves them out of creating the conversation. As a result, we often don't serve them very well. You can see how this ties into the inclusion/diversity issues in the theatre world. I wish that the questions you raise in this article were included more in that debate, too.

Thanks! I've noticed this becoming more of a topic of conversation so I'm hopeful we'll start to see some initiatives to increase diversity throughout the industry.

As former Internship Coordinator at Center Stage (in Baltimore), I embraced increasing diversity. I tried many ways to do this but continued to be frustrated by my lack of success. This starts in the schools, where arts programs in the public schools (particularly in inner cities) were increasingly cut, so a career in those subjects never even enters the realm of possibility. Because of college fees, there is an emphasis in choosing a career that pays, and that whittles down the field even further. I believe that Center Stage had one of the best programs in the country. We provided studio apartments owned and controlled by the theatre, that were in walking distance. We provided stipends so that given the free housing, utilities, etc., interns could subsist, particularly if they earned additional money and tips working at the theatre bars. Training and personal development were emphasized, as well as access to networks. I regret very much my limited success in recruiting minorities.

Great article! Thank you for shining a light on a problem that not discussed enough.

Thank you for reading!