Sophia Skiles: The impulse to reach out to you for a conversation was to prepare and be really clear-eyed about what I was walking into, in terms of assuming a leadership role—in my case, as the incoming head of acting for the Brown/Trinity MFA program. What does that mean in the context of this field-wide mandate of change? How would it sit in my body and what is the exposure that leadership involves? I wanted to have that conversation with folks who are going through it, and with you specifically, as you recently joined the acting faculty at the Yale School of Drama.

I am so deeply inspired by your leadership, which has been a long time coming. How are you navigating? Are you getting what you need, given that in this moment institutions are “lifting up” the leadership of folx of color, women of color? And there’s upheaval around that. What does it mean to be in those spaces where the architecture is changing in terms of people? How do you actually bring cultural change as you encounter resistance—often by the very folks or institutions who are there to lift you?

Nicole Brewer: I appreciate this effort to connect back to our bodies as people with a certain set of lived experiences coming into this work. For me, that’s a restoration of humanity. I am not above the pain and suffering I live with and through every day. I am also navigating analyses of institution, racism, gender, body, life experience, and self-determination within the positionality of leadership and creating the container for folks to be present in the fullness of themselves. How do we, as leaders, do that?

The question I’m thinking about in my current position is how to give students space to make decisions that make sense for them, which of course is going to impact their training. I was trained not to question the training. I believe it was Stella Adler who brought a throne-like chair into the classroom. That’s what I inherited, that idea of literal elevation. The master teacher who taught in my program, who I refuse to name because of her role in my erasure, was literally on a platform—that’s where her little desk was.

Sophia: I have also refused to name someone in my training experience. The person who took my time is not credited in any of my narrative. I do not include that person. And there’s joy in that reclamation, but my goodness, there’s pain.

What is that other way of training? There’s got to be another way.

I’m always trying to encourage people to develop their artistry based on who they are in that moment. The phraseology I use is: “What’s your most forward-facing identity?”

Nicole: There are many other ways. I’m always trying to encourage people to develop their artistry based on who they are in that moment. The phraseology I use is: “What’s your most forward-facing identity?” As people gain new life experiences, as they have identities thrust upon them, what’s the most forward-facing? And, therefore, what are the questions and analyses they have? Especially in a setting of “study.” What are they dealing with? What are they actually able to hear in the moment?

As human beings we are concerned with ourselves and what’s happening for us. What about people who are in a place of study who are dealing with issues of their sexuality or issues around their gender? First of all, they’re looking for representation, confirmation, and corroboration that their experience is valid. Representation is an important factor, as is space to unpack how identities inform your craft. How does training provide that? This is a question I’ve been chewing on for a solid decade around cross-cultural collaborations. How do curriculums support the most impacted folks? How do cross-cultural curriculums become the norm?

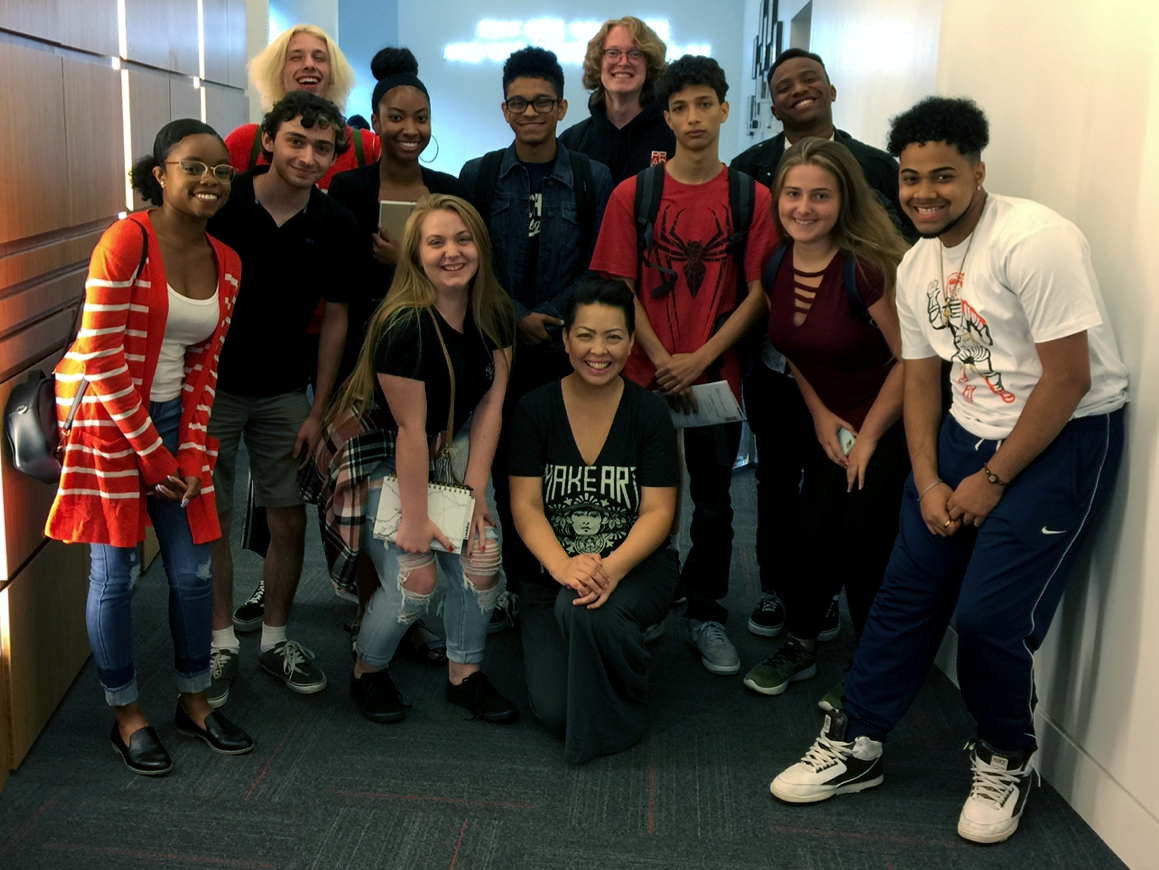

Sophia: Being open and finding ways to connect—that is a skill set, a muscle I have developed through my journey as an artist. That can be the way to fuel training. Where I have experienced marginalization, as a woman, as an Asian American, as a daughter of immigrants, there is also insight, power, points of connection though the violence of assimilation has threatened to erase my superpowers. Those are the things I can offer—as a teacher, a creative artist, and citizen—which I can take from marginalized spaces and reclaim as center.

My role as the head of acting for the Brown/Trinity Rep MFA program is ahead of me. I’m not in it yet, so I’m using this time to fortify myself, to look at models of leadership and look at ways to protect myself. That’s something Lauren Turner talks about in her essay on racialized trauma, “The American Theatre Was Killing Me.” Lauren’s telling of her experience as a Black woman working in a predominantly white cultural institution is revelatory. The challenges she describes are so intimate yet systemic. Things were happening so quickly she didn’t have time to process, to reclaim her center, to stabilize herself. So, in my new situation, what can I do to interrupt that and also stay sane?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

thank you for this. I feel fortunate to learn from your dialogue, and grateful to be able to share it with others.