Fueled by Fury

Finding the Language to Fix Us

This week on HowlRound, we continue our exploration of Theatre in the Age of Climate Change with more urgency than ever. With the looming eradication of climate science data from US government websites and the appointment of Scott Pruitt as head of the Environmental Protection Agency, Trump has indicated in no uncertain terms that the health of the planet and its inhabitants are of no concern to him. As theatre artists, how do we respond? Playwright Tira Palmquist and dramaturg Heather Helinsky offer their respective point-of-view on the writing and production of Two Degrees, a world premiere at the Denver Center, season 2016-2017, and how the elections impacted the development of the play.—Chantal Bilodeau

Tira Palmquist: The notion that I would write a play in which someone discovers the solution to climate change was never the point of Two Degrees (though I believe that climate change is a fixable, solvable problem). After all, there is no silver bullet, no singular, magical solution for this issue.

More to the point, how to fix climate change wasn’t really the question. To fix climate change, we have to move people from inaction to action, from doubt to conviction. Finding the language and the arguments to do this is clearly important, but in order to do that we have to ask the more important question: How do we fix us?

Day-by-day, by integrating a climate change topic and action-of-the-day, we dove deeper into the issues the characters were struggling with.

Heather Helinsky: As the dramaturg, I watched Tira make decisions about what needed to change in response to the election. I first came across the piece in 2014 at Great Plains Theatre Conference. In 2015, it was picked up by the Athena Project Festival in Aurora, Colorado, before it was invited to the Colorado New Play Summit in February 2016. Originally, the “villain” or antagonist of the play was cultural apathy. Over the summer, when director Christy Montour-Larson and I discussed changes, Tira decided to wait until after the election for final re-writes. After November 9, it became clear that the antagonist was not going to be any one person, but a toxic administration determined to roll back essential EPA regulations. However, there were many other aspects of the play that Tira kept intact. While the stakes for the protagonist dramatically increased because of the election, the problems and conflicts in the play were issues Tira has been contemplating deeply for a long time.

For example, when we met scientist Bruce Vaughn at the Institute for Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado Boulder, he explained that his answer to the question of whether he believes in climate change is "No, I don't believe in climate change. Climate change is a reality that exists, like gravity. I don't have to believe in gravity. You can have your own opinion but you can't have your own physics." So it is for the play as well. What's up for debate now, are the choices, large and small, being made in our legislation and the way we live our lives.

Tira: Two Degrees follows the story of Emma Phelps, a paleoclimatologist who has been called to Washington, DC to provide expert testimony on behalf of the EPA (to protect the current regulations spelled out in the Climate Action Plan). Her struggle throughout the play is how to communicate with non-scientists, how to make her scientific findings clear and understandable. In a workshop a few years ago, I worked with a young PhD student in climate science, and she told me that she could relate to Emma’s struggle of how best to communicate that science.

Many scientists are frustrated by the accusation that they unnecessarily obfuscate what they mean while in reality, scientists write in careful and moderate language to be clear and unambiguous, stripped of any emotional noise or dissonance. The depressing reality is that, to non-scientists, this careful and moderate language often reads as unsure or uncertain. To scientists, more dramatic, more intense language is read as being “alarmist.”

So, how do we bridge that gap?

Heather: In rehearsals, we talked about the many different languages in this play: Greenlandic, an indigenous language disappearing as fast as the arctic ice; the aggressive language of Washington, DC politics; the careful, measured, passive voice of the scientists; and finally, the language of grief (if there is, indeed, a “better” way to grieve).

The conflicts between these languages easily created dramatic tension and deeply-layered subtext. I could easily dramaturg that. That’s the kind of detailed, language-driven playwriting that makes a new play operate like a classic play. Each character is wielding words like swords to land their point.

Tira: In the play, Emma is encouraged to present her arguments in “real, human terms” to her audience of non-scientists. The problem with this is that climate science is such an enormous, complicated topic that “real, human terms” can seem elusive.

In a scene between Emma and Jeffrey, their playful banter about language underscores the heart of the divide between language purists and scientists:

JEFFREY: (Pointing at the page) You can't change the passive voice here?

EMMA: Where?

JEFFREY: "...the heavy oxygen isotope O18 is measured..."

EMMA: Well, it is measured.

JEFFREY: By whom?

EMMA: It doesn't matter by whom.

JEFFREY: It doesn't?

EMMA: Not here. Not in this paragraph. This is not a personal statement, Jeffrey. It's a report.

JEFFREY: Yeah, I get that. It just sounds so... removed. Careful.

EMMA: That is exactly how it's supposed to sound. I don't want to sound like an alarmist.

JEFFREY: I dunno. It's pretty fucking alarming to me.

So, how do we convince people that this is a very, very alarming situation indeed? This became the central conflict for Emma—to learn a new language, in effect, to alarm without being an alarmist. This change isn’t easy for Emma—though it probably seems easy for those of us outside the scientific community. The danger for Emma is that speaking about science in “real, human terms” can dilute the facts, or can obscure or twist the facts—and that’s the last thing a scientist wants to do. The data need to be conveyed in a clear, organized fashion, and the way one communicates can’t warp or misconstrue the data.

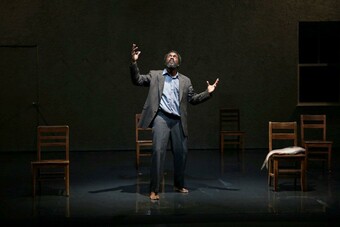

Heather: As collaborators in the rehearsal room, we also needed to learn a new language. We decided to take five to ten minutes out of every rehearsal for dramaturgical conversations. Tira and I would discuss an article about climate change every morning, then we would pair it with an “Action of the Day” to share with the cast and creative team. This wasn’t an extraneous thing we did; it was within the spirit of the production: to understand how we, as a creative team, needed to be more informed and change. Day-by-day, by integrating a climate change topic and action-of-the-day, we dove deeper into the issues the characters were struggling with. Actor Robert Montano said at the end of the project that our dramaturgy made him passionate about the very things his character was passionate about.

Tira: The arc of the play, finally, is that Emma shifts from researcher to advocate, but it’s more fundamental than that. She changes from being frozen to being ferocious. She becomes a champion. A warrior. Instead of tamping down her fury, she lets that fury fuel her language. If the rest of us are going to speak out on behalf of science, of the planet, of the future, then we need to be fueled by such fury.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I love the Action of the Day idea! Can you share any examples of the kinds of actions you all took? :)

I was lucky enough to see the beautiful production in Denver. What I remember most is the personal journey of grief that the main character goes on both for the planet and for the previous loss of her husband. I identify with that visceral grief, both for the loved ones I've lost, but also for the Earth. It's a real, palpable response to what is happening. I hope this important play finds the wider audience it deserves!

Thank you, Tammy!

Loved this piece when I saw the reading at GPTC - so excited to see that it has received the development opportunities/resources it deserved, and that it continues to reach wider audiences :-)

FYI: A Clarification! I do believe that climate *is* a fixable, solve-able problem -- It's just that I don't believe there is a magic bullet solution. Climate change will be solved by *many* little solutions.