Gender Parity in Canadian Theatre

Rebecca Burton is the Membership and Professional Contracts Manager and one of the founders of the Equity in Theatre (EIT) initiative at the Playwrights Guild of Canada (PGC). I was the founding co-chair of the International Centre for Women Playwrights (ICWP) 50/50 Applause Award and I am based in the United States. Together, Rebecca and I have been collaborating towards gender parity for women playwrights across our borders since 2012.

Elana: I don’t think I’ve ever asked you how you came to start working towards this goal.

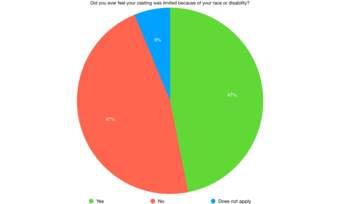

Rebecca: I was an actor first and then decided to go the academic route. I focused on feminist theatre but realized that there was very little written about it, especially in Canada. The perception that women were underrepresented and disadvantaged in theatre wasn’t believed. So, in 2006, I conducted a study on women in Canadian theatre called “Adding It Up.” I was hired by PGC, a feminist women’s theatre company called Nightwood Theatre, and the Professional Association of Canadian Theatres (PACT). The point of the study was to find out real numbers and work towards greater equity activism. But the report wasn’t well received. No one wanted to hear it. No one would publish it. No press, no academic body, no industry journal. I wrote some articles about the study but no one published the report in its entirety.

Elana: I remember that study. It wasn’t well received at all?

Rebecca: When I did a presentation for PACT in 2006, I couldn’t even get through it! They kept interrupting me, questioning the methodology, and refuting the results.

Elana: What was in the study that was so objectionable?

Rebecca: The primarily white, male artistic directors did not appreciate being told that they were being biased, mostly unconsciously, as well as discriminatory in their hiring and programming practices. They were receiving a large chunk of funding for work, targeting male audiences, when our study proved that the majority of audiences were women.

Elana: What else did the report say?

Rebecca: It provided statistics and concrete evidence, once and for all, that, in the twenty-first century, the Canadian theatre industry was still biased and discriminatory, that it operated along stereotypically gendered lines (the majority of designers were male except for costumes, and women were paid less), and that it disproportionately overrepresented white men. The larger the company and the budget—which often comes from taxpayers’ money here—the worse the representation for women and people of color. The report identified remaining barriers to gender equity and made recommendations.

Elana: What has changed since 2006? How is it for women playwrights and women in theatre in Canada now?

Rebecca: No one was interested in gender equity in 2006. We approached stakeholders to create a Women’s Initiative but only women practitioners were interested. The Women’s Initiative was made up of various individuals, spearheaded by the Women’s Caucus of the PGC, which was run by Hope McIntyre, and Nightwood Theatre, headed by Kelly Thornton. It’s a very different story now, a decade later; the industry’s major stakeholders are all interested and actively pursuing greater equity and inclusion.

Elana: Were you working at PGC then?

Rebecca: No, I didn’t start working there until 2012. Every year, PGC does a production survey and they analyze the gender breakdown of the playwrights being performed nationally. The first three years I worked with them, there was a regression in the number of women being produced—it went down below 25 percent.

Elana: Wow! And 25 percent is a good number, compared to the rest of the world. Canada has always seemed to me, being from the United States and studying numbers internationally, to be ahead of the rest of the world for gender parity for playwrights. Almost all other countries have individually lower percentages. How do you feel Canada is doing now?

Rebecca: We’re getting there, slowly but surely, and a lot of that has to do with work being done by other kinds of marginalized communities. The Canadian government officially made Canada a “multicultural” country in the 1970s (otherwise, we are officially bilingual: French and English). Once you start looking at the stats, however, one sees that the theatre has been geared towards men, and white men at that. So, it may be that we are further ahead in relation to gender-based statistics, but we are lagging behind our own official policies. Canadian theatre has not traditionally represented or been geared towards women, or Indigenous folks, or people of color, or non-Anglo/ Francophone cultures. How can we claim to be a multicultural society when our culture doesn’t reflect that fact or the actual demographics of our population? The sense here among many has been that we’ve talked the talked, but not walked the walk.

As well, multiculturalism came to have some negative connotations attached to it, since it tended to be used by government and others to highlight traditional customs and the past (museum pieces), rather than the current, living, breathing, vibrant cultural practices of people who aren’t white and Anglo or Francophone. As a result, many of us reject the multiculturalism label here, as well as the current use of the term diversity (which is incorrectly used as a catchall to mean people of color), and instead opt for the phrase “pluralism” or “cultural pluralism,” meaning to recognize and embrace many different people and styles. The idea is that there is room for everyone to maintain, expand, and hybridize their own artistic and cultural practices within the larger overarching culture.

So, Canada has been working on greater pluralism, particularly involving women, Indigenous Peoples, and people of color, since the 1970s. Last year, the Canada Council for the Arts, which provides funding to Canadian theatres to reflect our population, prioritized three communities: people of color, Indigenous Peoples, and people with disabilities. They didn’t include women or LGBTQ+ communities, but it’s a start. So there has been a shift there as well. And, in 2014, when we launched the Equity in Theatre initiative, people were much more receptive than in the previous decade. Most heads of the organizations—not the theatres, but the service organizations—were women. So perhaps that made it easier to start the conversation.

The point of the study was to find out real numbers and work towards greater equity activism. But the report wasn’t well received. No one wanted to hear it. No one would publish it.

Elana: Let’s talk about Equity in Theatre. What were its original goals?

Rebecca: I really wanted to draw attention to the fact that the stats for women playwrights had been regressing. On the one hand, some people had been sitting there thinking that feminism was a done deal; it accomplished all it needed. On the other hand, when my colleague Laine Zisman Newman and I started talking to activist people, we discovered that they were sick to death of talking about the issues; they had been doing that since the 1960s. They wanted action.

Elana: And who is Laine?

Rebecca: Laine was working as a dramaturg for Pat the Dog Theatre Creation in Kitchener, Ontario. Her boss, Lisa O’Connell, and my boss, Robin Sokoloski, were collaborating on another project and discovered that they both had staff members who wanted to work on a gender equity project, so they suggested we get in touch.

Elana: So you two got together and dreamed up EIT?

Rebecca: Yes. Our main mandate was to identify problem areas, find ways of remedying the problems, and create concrete actions aimed at that. We took a four-pronged approach. The first step was another research study with an independent researcher, Dr. Michelle MacArthur. The second was a website for EIT on gender parity that would serve as a hub, since none existed in Canada. It has links to information on gender parity worldwide, and we also included a directory of female theatre practitioners to increase hiring for women.

Elana: That sounds like a fantastic idea. The United States needs one of those!

Rebecca: It was the most-used part of our website. The third thing we did was hold a one-day symposium that brought all kinds of people together in the industry, focusing on problems in the morning and solutions in the afternoon. Several Americans got excited and contacted us in advance of the symposium: Martha Richards from WomenArts, Shellen Lubin from Women in the Arts and Media Coalition, and others from the League of Professional Theatre Women.

Elana: And we had some US-based members from ICWP attend.

Rebecca: With so many Americans suddenly wanting to attend, we added a second day and had Dr. MacArthur come in to talk about the research from the report. We didn’t quite manage to do everything we wanted to with the symposium, though. The overarching grand plan was to hire a facilitator to conduct the whole process and develop a five-year strategic plan to help fix gender inequity in Canadian theatre as a whole, but we didn’t get enough money to do that last aspect of work. So, we held the symposium and made an in-house toolkit called Change in Action, which offers a seven-step plan to advocate for anything, creating change through social action.

Elana: The symposium was talked about a lot in the United States at the time. Everyone who was working on gender parity wanted to go. How unfortunate, though, that you were unable to accomplish all of your goals for it. Maybe you’ll find someone who will want to help you finish that. What was the fourth thing?

Rebecca: The fourth thing that EIT did was community events and social action across the nation to draw attention to women artists, including a reading series with sixteen playwrights held in eight cities to celebrate International Women’s Day; a hackathon to increase visibility of women artists on the internet (we use Performance Wiki, a Canadian site), which we did for three straight years; and panels tailored to each region that discussed everything from controversial casting issues in Vancouver (such as selecting white people for Latinx roles) to producing the work of lesbian playwrights in Halifax.

There are places here where men and women can go through their entire theatre education without experiencing a mainstage production by a woman playwright.

Elana: I saw that you recently partnered with Women’s Playwright International (WPI) to found a new award called CASA, honoring South African female playwrights. How did that happen?

Rebecca: There has been a contingency of Canadian playwrights who have been attending the WPI conferences since 1988. I was among the eight people who went to the South Africa conference in 2015, and we noticed the South African practitioners there were mostly directors and actors and they were selling plays by men, not women.

Elana: You’re kidding!

Rebecca: When we asked where the female playwrights were, they said that there were very few of them due to a number of factors, including an oral and improvisational tradition, a lack of funding, and a need to care for family. When we got back to Canada, Beverley Cooper (a playwright who was on the trip) turned to the rest of us and said: “We have to do something about this.” She decided to start an initiative to offer money to a mid-career woman playwright in South Africa to buy her three month’s writing time. Cooper received money from an anonymous donor who committed to four years. This year, the committee in South Africa chose three emerging playwrights to split the money, instead of one mid-career, since they didn’t have anyone who fit the intended criteria well.

CASA also has a mentorship component where South African playwrights are matched with Canadian women playwrights. There’s a South African lesbian playwright and, you know, that’s not something that’s okay in Africa still, and she was paired with a Canadian lesbian playwright, which allowed her to write a play that she’s always wanted to create.

Elana: How wonderful! What a great use of international relationships and what a fantastic way to support each other. PGC has some other new and very exciting projects launching, like PLEDGE. How did that come about?

Rebecca: PLEDGE, which stands for a Production Listing to Enhance Diversity and Gender Equity, was developed out of EIT and just had a soft launch. Laine and I had guest-edited an issue of the Canadian Theatre Review and dedicated to the issue of gender equity. One article was about gender equity in post-secondary schools (colleges and universities), and we discovered that their programming of women playwrights was even worse than our professional theatres: 18 percent overall.

Elana: That’s as much as the US was producing women back in 2009 when the Emily Sands report came out.

Rebeccca: I know! We couldn’t believe it. These are the people who are training our theatre professionals and, yet, there are places here where men and women can go through their entire theatre education without experiencing a mainstage production by a woman playwright. What we mostly heard as the reason for this was “I don’t know any plays by female playwrights” and “I need large-cast plays.” So we created PLEDGE, a database of large-cast plays, six characters or more, written by women playwrights. We currently have over three hundred plays and the database is searchable by genre, theme, playwright, cast size, and other factors. PLEDGE is in partnership with the University of Toronto-Scarborough Campus and spearheaded by Dr. Barry Freeman through the Department of Equity and Diversity in the Arts. They are really ahead over there. He is the one who contacted us and found the funding for the database. We will do a hard launch in May and the hope is that post-secondary schools will make public pledges—that’s why we named it that—over the summer to produce more plays by women. Currently, we only have English-language plays but, next year, we will be accepting French and other languages.

Elana: The United States could use one of those, too. We are all clearly influencing each other in our work. I know you’ve gotten inspiration from us on something, too. The Kilroys List has been successful in highlighting contemporary women’s work in the US and you’re planning something similar, right?

Rebecca: Yes. We are calling it the Surefire List. We have a list of two hundred recommenders made up of artistic directors, critics, dramaturges, and others, and we are asking them for their top three “passion picks” of unproduced or under-produced plays by Canadian women. It will probably be hosted on the Women’s Caucus page on the PGC website and we hope to release the list in September.

Elana: What is some advice you would give to theatres, or people in the industry, that are trying to support women in theatre?

Rebecca: Please do so! Yes, you can have more women on boards and more female artistic directors, but track it back to the playwrights, too. It all trickles down from there. Plays by women tend to have more roles (and meatier ones, at that) for women and they provide more work opportunities for women designers and directors. Also, don’t try to solve the whole problem, because you can’t. But pick one area, focus and act on that, and watch how it ripples out from there.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Now is the time to encourage the Canada Council to conduct a study into their own granting practices for organizations and individuals. Best to look at recent studies at NFB and Telefilm as they separated out mixed gender groups. Just gathering stats from organizations is not enough. We need to see dollar for dollar what women and women-led orgs and collectives are granted.

I have long thought that going to the funding sources as a way to do advocacy would be the next move. I hope that Canada is ready for that move to be successful.