Create and Use a Closure Practice

A closing ritual at the end of an intimacy rehearsal can be useful to seal the work. Especially if actors are working from home, there needs to be an opportunity to shake the work from the body before moving on with the rest of rehearsal or the day. Even when working in person, leaving the physical rehearsal space does not always release the interior feelings built up during rehearsal.

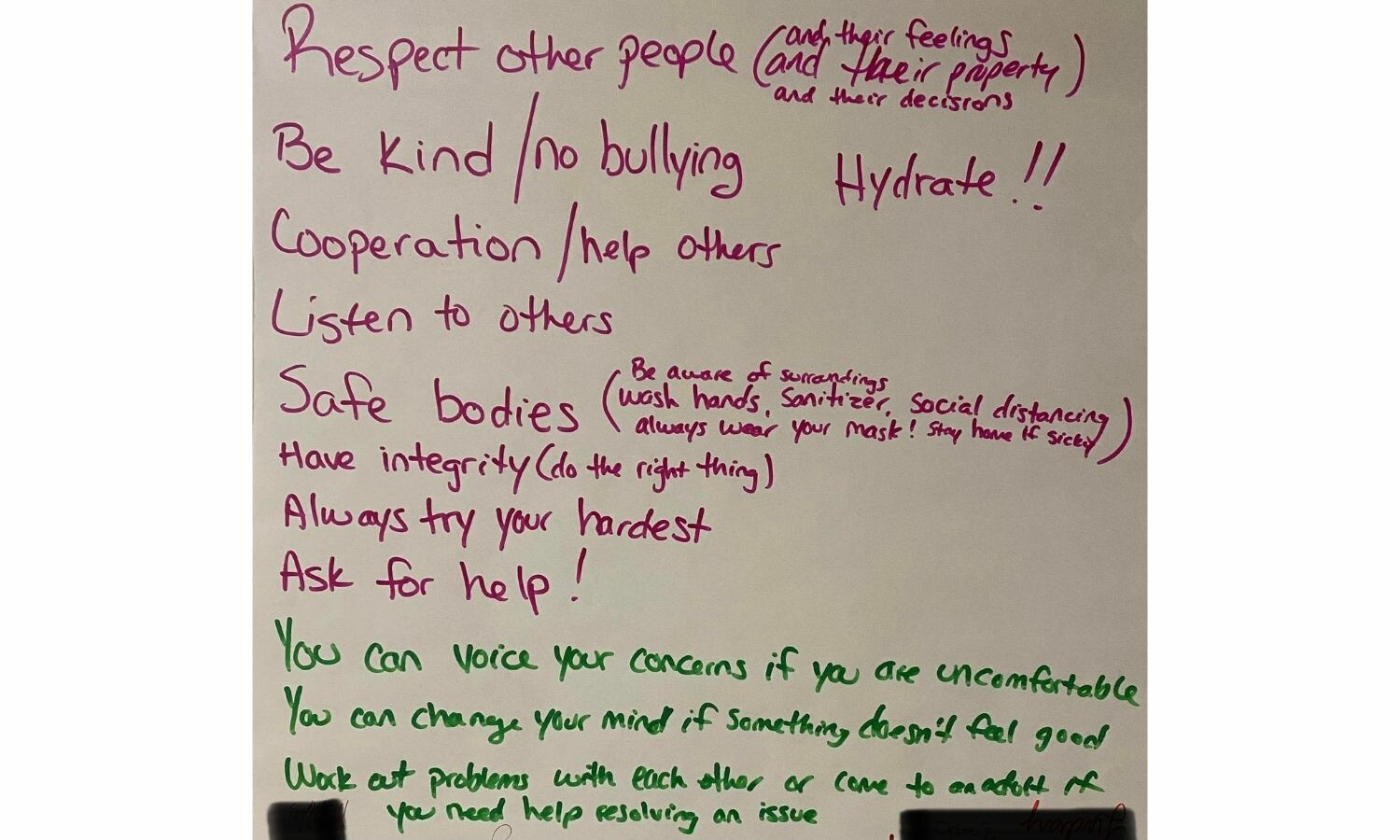

A series of different sensory practices help to ground actors back in reality and leave the world of the play behind. We might shake it out, yell into the void, drink water, take some calming breaths, power clap, or any combination of those things. Closing ritual can be anything and should be developed as an ensemble, but it becomes most effective over time, as our brains begin to associate the act as a marked transition between literal or metaphorical spaces. Conclude by thanking the actors for their work and vulnerability, recognizing the parts of themselves they have shared that day.

Use the closing ritual every time you meet.

Consider Your Audience

When staging intimacy, consider who will be attending the production. A large contributing factor to students’ discomfort with these scenes comes from personally knowing their audience. In educational theatre, the audience is mostly made up of family, friends, classmates, and teachers. It feels much different to perform on a professional stage in front of strangers than to perform in front of peers.

Consider the emotional and social impact the intimacy scene will have on the actors performing.

Moving Forward

As theatre educators, we set the bar for how young artists and humans will expect to be treated and how they will treat others. We have a responsibility to demonstrate what a safe and consensual workplace looks like so that students may recognize potentially harmful environments as they go out into the world. When we treat students with respect and recognize that they have lives beyond the classroom, the classroom environment becomes a community that values reciprocity, safety, and mutual respect. Many teachers are struggling to follow through on statements of change and equity in the classroom. Part of dismantling the hierarchy includes recognizing our own toxic habits, holding ourselves accountable for change, and listening to students when they speak up.

There is still so much work to be done, and this is just the beginning of the conversation. What are you doing to build a culture of consent in your classroom? What is working for you or what do you want to try? What resources around this topic do you wish you had, either for yourself or your students? The development of best practices cannot successfully be done in isolation—we have to do what teachers do best: share resources and talk to each other! I want to hear from you.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thanks for the article! It's wonderful, as far as it goes. This really focuses on rehearsal processes and not the classroom. I find it much more challenging to figure out the difficult lines of respecting students' autonomy while challenging them to be emotionally open in actor training. With such an inherent power imbalance, how do we get genuine consent for emotionally vulnerable work? I'm I would live to hear other teachers' ideas.

Hi Jen! Yes, I agree that the classroom definitely poses unique challenges from the rehearsal room. It can be difficult to find the line between encouraging students to move outside of their comfort zones and violating their autonomy. Similarly to the steps suggested in this article, I think a lot can be accomplished through careful and thoughtful conversation with students who are hesitant. I also think a scaffolding approach, working up to the more intense emotional intimacy, could be effective. Using exercises such as the ones linked in the article can help to build trust in the classroom and start to level the power dynamics between teacher and students so that students feel more empowered to speak up if they are uncomfortable. I also think a lot of what you're asking comes down to assessing the levels of risk. Is the emotional intimacy/vulnerability possibly triggering trauma in a student, or are they nervous to be vulnerable in front of classmates? If the groundwork has been established to build a brave classroom space where students trust each other and the teacher, some of that hesitation might be more easily assuaged. There's a lot to discuss here and I would also be interested to hear from other teachers!

Thank you for this insight and guidance! I was looking at doing the first-ever Shakespeare at my school and chose "Romeo and Juliet" as it is my favorite. The students were passionate about it, but I struggled with managing the intimacy; these are beneficial guidelines and resources.

Thanks, Keith! I'm glad this was useful for you and I wish you luck on your next production!