"On the Far Side of Revenge"

The Plays of Seamus Heaney

By 2003, Sophocles’ Antigone, a fifth century B.C. tragedy about a violent confrontation between a defiant young woman and an arrogant ruler, was one of the most widely adapted plays in Ireland.

When Seamus Heaney was invited to translate Antigone for the Abbey Theatre’s centenary program in early 2003, he wondered, “How many Antigones could Irish theater put up with?” The multiple retellings had employed the Greek tragedy as a form of reckoning with contemporary geopolitical crises—wars, injustices, moral and political corruption, and dictatorships.

Conall Morrison’s much lauded adaptation set the play in the context of a suicide bombing and global terrorism in the early 2000s. Tom Paulin and Brendan Kennelly’s versions transported the play to a troubled Northern Ireland in the last third of the twentieth-century. When Heaney undertook his own version of the play, renaming it The Burial at Thebes (2004), he had arrived at a solution to the dangers of staleness and repetition—a mingling of poetry and politics.

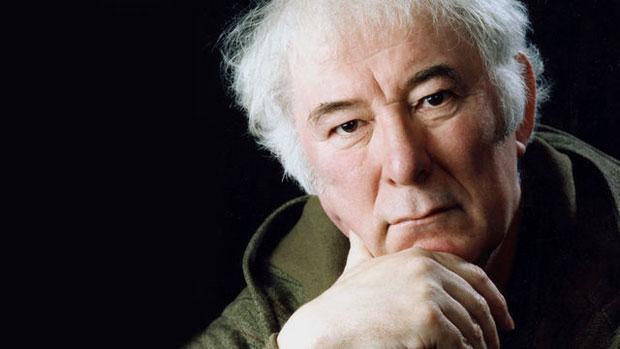

Seamus Heaney, who recently died at the age of seventy-four, once confessed that drama offered him greater artistic freedom than poetry. In his plays—adaptations and translations of Sophocles’ Greek tragedies—the dramatic action involves the nitty-gritty of ethical dilemmas and human life, balancing impassioned rhetoric with transparent sentiment.

While Heaney authored over a dozen collections of poetry, he wrote only two plays—both in verse—The Cure at Troy (1990) and The Burial at Thebes. The plays offer an interesting study of contrasts: they are balanced between the archaic and modern, between invention and adaptation, between politics and aesthetics. Both plays were commissioned by theaters in Ireland and they remain very much enmeshed in questions of the nature of literary forms and fractious contemporary politics in Ireland and elsewhere, and how best to bring together politics and dramatic form.

His first play, The Cure at Troy, a version of Sophocles’ Philoctetes dramatizes the deep rift between individual morality and patriotic duty. Oedipus and Neoptolemus, the young son of the dead warrior Achilles, plot ways to either lure Philoctetes to Troy, or somehow procure Hercules’s bow and arrows which are in Philoctetes’ possession. According to a prophecy, Hercules’ weapons would help the Greeks win the war against the Trojans.

Philoctetes is the Sophoclean version of Caliban, an outcast from society suffering from the curse of an incurable, foul-smelling wound, living a brutish life on the desolate island of Lemnos. He was “marooned,” left to perish on Lemnos by Odysseus and other Greek soldiers after they could no longer withstand his howls of pain and the stench of his wound.

Neoptolemus is charged by Odysseus to obtain the bow and arrows from Philoctetes by stealth and cunning, and the chief tension of the play turns on the conflict between Neoptolemus’s natural desire to not wrong Philoctetes and his obligations to his fellow Greek warriors.

After ten years in the wilderness of exile, Philoctetes is more animal than human; he continues to suffer terribly from his wound and is consumed by his rage toward Odysseus and his former Greek compatriots. In Heaney’s brilliantly balanced rendition, Philoctetes is a victim of the wily Odysseus, but he is also his own worst foe; the Chorus admonishes him, “Your wound is what you feed on, Philoctetes.” But Philoctetes is also a Greek hero, who ultimately regains his lost glory when Neoptolemus persuades him to rejoin the Greeks and fight the Trojans: “The hero that was healed and then went on to heal the wound of the Trojan war itself.”

Heaney would have found in the notion of a healing of a suppurating wound the echoes of the possibility of the reconstruction “of the wounded spots on the face of the earth”—“of Ulster and Israel and Bosnia and Rwanda.” In an interview, Heaney explains that his decision to rename Philoctetes and call it the The Cure at Troy was inspired by Irish Catholic religious beliefs. “In Ireland, north and south, the idea of a miraculous cure is deeply lodged in the religious subculture…”

The dramatic action involves the nitty-gritty of ethical dilemmas and human life, balancing impassioned rhetoric with transparent sentiment.

Neoptolemus’s struggle between his duty toward the Greeks and his innate moral principles held a special allure for Heaney. His spiritual battle became a metaphor for the dilemma faced by Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland—would, to paraphrase Heaney, speaking truthfully on certain occasions mean that you are letting down your side? The hidden connection between Sophoclean theater and Irish politics emerges vividly in Heaney’s 1995 Nobel lecture in a searing criticism of the notion of a too narrowly conceived “political solidarity” that blinded one to “poetic truth” and the change that could transpire when Catholics and Protestants could reach beyond sectarian loyalties and partisanship to forge fragile alliances.

In Neoptolemus’s decision to rise above the “side” of his peers and generously bring Philoctetes back to human society, to the sphere of fellowship, influence and power, Heaney glimpsed an ideal order, an alternative to the long history in Northern Ireland of “hardening attitudes and narrowing possibilities… Of political solidarity, traumatic suffering and sheer emotional self-protectiveness.”

Heaney took some liberties with his translation of Philoctetes, a notable change being the addition of an extra chorus to the play, which, ironically, went on to become the most famous lines in The Cure at Troy (Nadine Gordimer called her 1999 book of essays Living in Hope and History):

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.

For a poet of elegies on lairs of ossified bones and skeletons in peat bogs and marshes, who called himself “Hamlet the Dane,” “skull handler” and “smeller of rot,” this choric verse is undeniably optimistic and hopeful about the value of human action. However, after watching performances of The Cure at Troy, Heaney questioned the value of the intersection between contemporary politics and dramatic aesthetics. He wondered if the play’s anachronistic, modern choric references to the “innocent in gaols,” “hunger strikes,” and “the police widow” couldn’t be faulted for a certain intrusive didacticism; “Once the performances started, I came to realize the topical references were a mistake. Spelling things out like that is almost like patronizing the audience.”

Heaney’s ambitions for his later play, The Burial At Thebes are decidedly artistic in nature—a desire for greater fidelity to the original Antigone and a quest for the right sort of poetic meter. Heaney’s version of Antigone was commissioned for the Abbey’s centenary program in the midst of America’s global war on terror, the invasion of Iraq and the erosion of civil liberties. The political circumstances were certainly ripe for a play on the unchecked powers of a ruler and the arbitrarily imposed distinctions between a traitor and a patriot. Heaney’s adaptation of Sophocles’ drama was also meant to complete an Irish literary tradition that had started when W. B. Yeats had adapted Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus and Oedipus the King for the Abbey in the 1930s.

At the heart of the play is the issue of the burial of Antigones’ brother Polyneices. Labeling him a traitor, Creon orders his corpse to be left unburied, to decompose in the open air, and to be devoured by animals and birds. Antigone defies Creon’s tyrannical edict and performs burial rituals for Polyneices. Flinging aside Creon’s mortal law, Antigone’s claims to act under the greater charge of an immutable god-given moral compass, “Religion dictates the burial of the dead.” Heaney renamed his version of the play, Burial at Thebes, placing front and center not the titular heroine of Sophocles’ play, but the object of savage persecution and violence—the corpse of a presumed traitor.

Heaney’s adaptation wrestles with the question of how to make an “overfamiliar” play pulsate with captivating voices and poetic rhythms of such metrical variety that the modern viewer would find the play a profound and joyful experience. Heaney, who was not familiar with Greek and worked from multiple translations of each play (some of which closely followed the “metrical shifts of the original Greek”) called his endeavor “an ongoing line-by-line, hand-to-hand engagement with the material.”

In order to capture the right meter and pitch for the modern stage, Heaney turned to an eighteenth-century Irish lament in the voice of a woman who is grieving over the body of her husband lying on a roadside in County Cork in much the same way as Antigone is distraught that Polyneices corpse is abandoned outside Thebes. The poem furnished Heaney with the lean, deft and conversational meter (“the three-beat line”) to fashion dialogue as well as the voice, tone and pitch of the play for contemporary audiences; Heaney also employed a mix of the Old English Anglo-Saxon meter from Christian hymns and the traditional iambic pentameter.

Here is the crystalline, sharp and quietly wrenching speech of Antigone after she is condemned to die by Creon:

No flinching then at fate.

No wedding guests. No wake.

No keen. No panegyric.

I close my eye on the sun.

I turn my back on the light.

The singular achievement of Heaney’s verse drama is that it fulfills his own fond hopes for an art that is “not only pleasurably right but compellingly wise, not only a surprising variation played upon the world, but a retuning of the world itself.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Excellent review of Seamus Heaney's plays. Thank you.