Seattle’s eSe Teatro

An Avant-Garde for the Undocumented

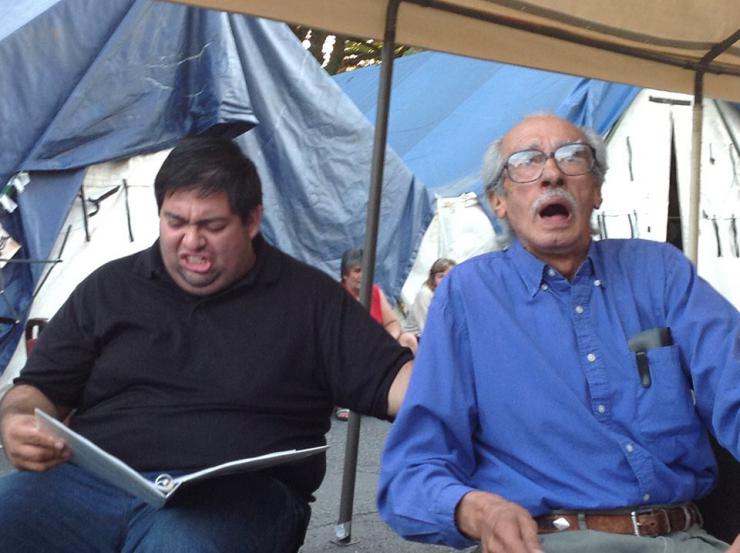

I first met Rose Cano, the Artistic Director of Seattle’s eSe Teatro, at a staged reading of Enrique Urueta’s Learn to be Latina, a “post-9/11 farce with dance breaks” hosted by the University of Washington’s Professional Actor Training Program in the Spring of 2014. And even though Urueta’s irresistible theatrical assault on the conventions of celebrity, ethnicity, and sexuality did find its way into my upcoming drama course at the University of Washington, I did not attend the event merely to hear the play: I had a tip that Rose Cano would be there, so I went to hunt her down. I had seen her company’s ambitious production of Luis Alfaro’s Oedipus el Rey, (the play’s Seattle premiere), but had only heard about their on-going process of theatrical workshops with homeless and undocumented communities, something I wanted to know more about. It stands to reason that I hadn’t seen these performances. After all, these workshops (which eventually developed into eSe Teatro’s full production of Don Quixote: Homeless in Seattle) were being held in locations well outside the bounds of traditional theatre: Latina/o labor centers, drug rehabilitation centers, hospitals, and tent-cities of homeless Seattle citizens.

In essence, Cano’s play is a reimagining of Cervantes’ legendary novel, situating the two main protagonists (Quixote and Panza) as undocumented Mexican immigrants navigating the brutalizing experience of homelessness in modern day Seattle, a city that primarily finds itself identified with liberalism, sports, and technological progress (i.e. legalized marijuana, the Seahawks’ “12th Man,” and Amazon.com). But the world of Cano’s play is not the city of the elite, or the high profile sports fans, or the tourists, or even the middle class homeowners (itself an endangered population given the skyrocketing real estate market). The milieu of the play rather is the city’s subterranean realms: emergency rooms, hygiene centers, and communities who subsist beneath the noise-choked freeways. In effect, Don Quixote: Homeless in Seattle is a tour of the city’s darker side, and each scene takes place in an actual Seattle location. From the Washington State Convention Center, to the jornalero corner of a Home Depot parking lot, to the flea-infested midnight mission of Seattle’s historic Pioneer Square, Quixote and Panza traverse localities where the average citizen would dare not tread. Indeed they are confined to these spaces due to their status as both homeless and undocumented, a situation that (just like for Cervantes’ anti-heroes) often results in fatigue, hunger, confusion, violence, and ridiculous humor.

After four years of eye opening work at Seattle’s Harborview Hospital… Rose decided to take the stories she heard and put together a production that would attempt to capture the experience of homelessness in Seattle and also create a model of theatrical community engagement that might help alleviate some of the major issues that homeless people face.

But what kind of inhospitable ethnographic fieldwork would one have to conduct to be able to dramaturgically harness such real-life circumstances, incorporating not only the actual locations of the street, but also the language endemic to such locations? Enter Rose Cano. In addition to her life as an actress and theatremaker, Rose has been a Spanish-language medical interpreter in community clinics and public hospitals for the past nineteen years. She has interpreted both in people’s homes as well as institutional settings. After four years of eye-opening work at Seattle’s Harborview Hospital, where the vast majority of her patients are uninsured, of Mexican descent, and “non-citizens,” (either undocumented or permanent legal residents), Rose decided to take the stories she heard there and not only put together a production that would attempt to capture the experience of homelessness in Seattle, but also create a model of theatrical community engagement that might help alleviate some of the major issues that homeless people face. Thus her project to bring theatre to marginalized populations (a practice that I see as distinctly avant-garde, and for which she received a City of Seattle grant) was born. As Rose told me in an personal interview:

I wanted to do these reading at shelters [. . .] to do two things at once: to develop the art, and to serve a public need. We later called them ‘Dialogues with Dignity.’ We go to the shelters, read [the play], and see the response [. . .] At the same time we could illicit a dialogue that would be a catalyst for people to talk about how they felt about different things: about having a bad interpreter, or having no interpreter, what it’s like when they go to the emergency room, whether they have access to health care. It opens up a lot of conversation.

Over the course of two years, and multiple “Dialogues with Dignity,” Cano and her team of bilingual actors were able to adjust the dialogue in her script to more accurately reflect the experiences of the homeless audience members, and thus give a public voice to the population Cano considers her “co-author.” Now in their fifth year of existence, eSe Teatro is not only Seattle’s only Latina/o theatre, but also the one that may have the most serious commitment to harnessing theatre as a tool for social change. It is this kind of mission that harkens back to the origins of the avant-garde, not the “historical” avant-gardes of the early twentieth century Dadaists and Futurists, but the notion as first put forth a century earlier, in the 1820s, by the French utopian socialist Henri de Saint-Simon.

Saint-Simon and his disciples promoted a vision of futurity in which “the end of art itself was social utility.” Rejecting the old clergy of Christianity, artists (in their view) would emerge as a new kind of priesthood, the vanguard that would move mankind toward radically positive social change through their unique ability to imaginatively reconfigure material from the past. “In this great undertaking” [of well-being and happiness], Saint-Simon wrote, “the men of imagination will open the march; they will take the Golden Age from the past and offer it as a gift to future generations.” One art in particular, in which this transformed Golden Age would be offered in its most immediate form was identified by Saint-Simon’s disciple Olinde Rodrigues, who, according to Matei Călinescu, was the first writer to give the military term avant-garde its artistic context. Rodrigues wrote:

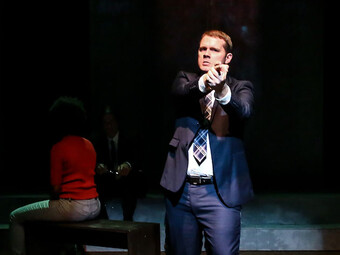

It is we, artists, that will serve as your avant-garde; the power of the arts is indeed most immediate and the fastest. We have weapons of all sorts: when we want to spread new ideas among people [. . .] the theatre stage is open to us, and it is mostly from there that our influence exerts itself electrically, victoriously.

There are many theatre companies in Seattle (some of them long-standing) that are doing experimental and fascinating work. But to my knowledge, it is only eSe Teatro that has recently attempted to brandish this “electrical weapon” of the stage, ripping a signifier from the Golden Age of Spanish literature, not only to search for new horizons of creativity, but also actively engage with a population that is essentially cut off from mainstream theater. Gad Guterman in his recent book Performance, Identity, and Immigration Law: A Theatre of Undocumentedness has incisively challenged high-ticket price theatre that purports to “speak for” the undocumented, indeed perform undocumentedness, while at the same time excluding that very population. “Undocumentedface,” Guterman provocatively calls it, and it is precisely this kind of moral pitfall that eSe Teatro attempts to avoid in the Don Quixote project by incorporating the voices of their homeless and undocumented “co-authors.” It is a project born in their space and on their terms.

But is representation of another (even an intimate other) ever quite as simple as all that? Any attempt by theatre artists to incorporate the true ‘voice of the people’ is contractually bound to the theatre’s age-old aesthetic of distortion.

But is representation of another (even an intimate other) ever quite as simple as all that? Any attempt by theatre artists to incorporate the true “voice of the people” is contractually bound to the theatre’s age-old aesthetic of distortion. Whether it is forged in a process that goes by “ethno-theatre,” “documentary theatre,” “verbatim theatre,” or “theatre of the real,” (among many other epithets) the performance text is always at risk of being lost in translation, effortlessly susceptible to the endless wormhole of Derridean différance. As it was with Don Quixote: Homeless in Seattle, the singular distortion of Cervantes’ original that was most upsetting to some audiences was Cano’s choice to turn Quixote’s “princess” into a murdered woman of Juárez.

Manifesting as a series of flashback correspondences that are tightly wound up with Don Quixote’s deteriorating mental state (his chronic inebriation eventually leads to his abandonment by Sancho), are the enacted letters from his beloved “Dulce,” a woman back home in Mexico who awaits his cash remittances. When neither the remittances nor any word from Quixote materialize, Dulce, desperate to support herself, migrates north and finds steady work at a maquiladora. Dulce’s letters (spoken in Spanish by an actress and whose lines are accompanied by a simultaneous English-language voice over) reveal that Dulce has the intention of crossing into the US to look for her beloved herself. Her distant narrative reaches the ear of the actor playing Quixote:

DULCE: I found someone to help me cross. He is a “coyote” named Frescón. They call him Frescón because he is cold-blooded. He never sweats. Not even crossing the desert. Not even when immigration stops him. El Frescón. My friend recommends him . . .

Later in the play, the final break in Quixote’s fragile mind is completed when Dulce’s correspondences eerily shift, emanating now from a locality beyond death. How he has received these “letters” from beyond remains a mystery, reifying the blurred lines between fantasy and reality for the displaced, undocumented hero. Whether a ghost, or a fiction in his wayward mind, his beloved explains:

He killed me. He killed me with my own hammer. Frescón. He took my hammer and left me in the desert. He threw me out of the truck and I don’t even know on which side of the border I landed.

Cano’s interpretation of Quixote’s misidentified princess Dulcinea is thus a metonym for the thousands of women and girls whose murders have gone unsolved in the border zones exemplified by Ciudad Juárez, a city where US corporations operate with little regulation, and whose endemic culture of impunity regarding its shocking rate of femicide has caused it to be deemed “The Murder Capitol of the World.” Reminiscent of recent plays such as Las Mujeres de Juárez, and Mujeres de Arena: Testimonios de Mujeres en Ciudad Juárez, which, according to Christina Marín, “attempt to give voice and dignity back to the hundreds of young women who ha[ve] been swallowed up by the border,” Cano’s distortion of Cervantes’ original did not sit well with a number of audience members. Undocumented laborers at Seattle’s Casa Latina, nearly all of whom have left loved ones behind in their countries of origin, were especially disturbed by the death of Dulce.

“Take that out,” Cano reported to me that some had said, “Why does she have to die?” Although they challenged Cano on the shear bleakness of Dulce’s outcome, they also extended their argument to the events of Cervantes’ novel as well, knowing full well that it is Quixote who dies (peacefully) at home, while his princess lived. Despite the protest of her “co-authors,” Cano allowed Dulce’s murder to remain in the play’s final version. To her thinking, the gesture of solidarity with the female victims of the neoliberalized borderlands was too important for her to leave out.

Given the complexities representing the underrepresented, fundamental questions emerge: would a happier ending best serve the political project that the members of eSe Teatro have set out for themselves? If so, would such an ending be a true reflection of the countless stories of social inequity that Cano has heard in the emergency rooms and homeless shelters? And if avant-garde art (at its core) is a weapon wielded to usher in a future in which the end of art is “social utility,” what are the stakes when that same art deeply aggravates those it claims to speak for? As eSe Teatro moves into its sixth year as the vanguard of Latino performance in the Pacific Northwest, my hope is not that they answer these questions for us, but that they continue to provoke all citizens of this city (documented or not) into answering the questions ourselves.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Mil Gracias/Thousand thanks, Christopher Goodson for excellent coverage of eSe teatro's noble work; one exception: the compliment " the vanguard of Latino performance in the Pacific Northwest " is a stretch: such belongs to Milagro Theatre/Miracle Theatre, Portland, with over thirty years worth of vanguarding.

Hi Jose. Thanks for reading and the article and leaving a comment. Much appreciated. And you are correct. I hope Jose Gonzalez et al. can forgive me the omission. More properly stated, eSe's intimate work with homeless and undocumented citizens constitutes a vanguard in Seattle. I wouldn't want to give the impression that they are the first Latino company in the Pacific Northwest. As you've pointed out, that would be far from the truth. Thank you.

Thanks to Christopher for this insightful and revelatory essay about Necessary Theater in the Pacific Northwest being created, nurtured and developed by Rose Cano and her collaborators. It is gratifying to see a SPANISH mythical character, Don Quijote, brought to life by some of our most ignored and invisible citizens (or not). Ms. Cano's work with the homeless must be made available to anyone with a heart and Christopher's brilliant essay starts the conversation beautifully. Way to go, Christopher!

Thank you Jorge for the comment. I look forward to documenting the contributions of Latino performers in the Seattle area, some of which fall decidedly outside the bounds of traditional theater. As far as eSe Teatro is concerned, I just attended their reading (in Spanish translation) of Hudes' "Water by the Spoonful." And Theater 22 is set to produce the Seattle premiere. Exciting stuff happening all the time.