Creating a Space for Black Theatre Audiences

With Addae Moon

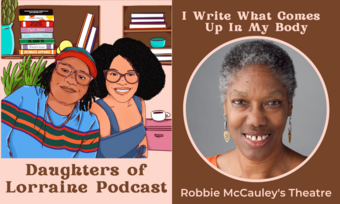

Leticia Ridley: Welcome to Daughters of Lorraine, a podcast from your friendly neighborhood Black feminists exploring the legacies, present, and futures of Black theatre. We are your host, Leticia Ridley—

Jordan Ealey: And Jordan Ealey. On this podcast, which is produced for HowlRound Theatre Commons—a free and open platform for theatre makers worldwide—we discuss Black theatre history; conduct interviews with local and national Black theatre artists, scholars, and practitioners; and discuss plays by Black playwrights that have our minds buzzing.

Leticia: Addae Moon is an Atlanta-based playwright, dramaturg, director, and teaching artist. Currently, he is the associate artistic director at Theatrical Outfit and co-artistic director and co-founder of Hush Harbor Lab. He was the former director of Museum Theatre at the Atlanta History Center, an artistic associate with Found Stages Theatre, and a resident playwright with Maat Productions of Afrikan Centered Theatre based out of Chicago, Illinois.

He has served as a resident dramaturg with Working Title Playwrights’ Ethel Woolson Lab working on developmental projects with local playwrights Neely Gossett, Johnny Drago, and many others. He is the recipient of the 2015 International Ibsen Award for his dramaturgical work on the project Master Comic and the 2014 John Lipsky Award from the International Museum Theatre Alliance for his immersive play Four Days of Fury: Atlanta, 1906. Addae was also a member of Alliance Theatre's 2015-2016 Reiser Artist Lab as co-writer on the immersive project Third Council of Lyons with Found Stages Theatre.

Jordan: As a former literary manager at Horizon Theatre Company, he served as dramaturg on the early development projects of many nationally renowned playwrights including Marcus Gardley, Lauren Gunderson, Tanya Barfield, and Janece Shaffer. As an educator, he is currently an adjunct professor in the Department of Theatre Arts at Clark Atlanta University and a playwriting instructor with Horizon Theatre Company's Apprentice Program.

Addae received his BA in Theatre Arts from Clark Atlanta University and an MFA in playwriting from the Professional Playwrights Program at Ohio University. In this episode, we sat down with Addae to discuss his thoughts on the state of Black theatre, his journey as an artist, and what makes Atlanta theatre so unique.

Hello, welcome back to Daughters of Lorraine. I am Jordan.

Leticia: And I am Leticia Ridley.

Jordan: And we're so happy to be back today. We have a really, really, really, really, really special guest. Today, we have the illustrious Addae Moon joining us today at our podcast. Hi Addae.

Addae Moon: Hey, y'all I. I feel like I've made it because I've made the Daughters Lorraine Podcast, hands down my favorite theatre podcast. I feel like I'm a big baller right now.

Leticia: I feel like we made it. We got you on the mic. We made it.

Jordan: I know.

Leticia: We have to start raising our price.

Addae: Right?

Jordan: For those of you who may not know, Addae and I have known each other for a few years now.

Addae: It's been a minute.

Jordan: I met... Yeah, it's been a minute. I met Addae when I was a playwriting apprentice at Horizon Theatre Company and he mentored all of the playwrights. I would say that we had a really excellent cohort of playwrights, and we've just been in touch ever since. I'm so happy that you're able to come on the podcast and talk to us about Black theatre and your journey and everything like that. At first, thing we'd love to know is if you could just introduce yourself to our listeners and some of the things that you are doing or how you identify yourself within the theatre and we'll get into more nitty-gritty questions after that.

Addae: I'm Addae Moon. I am an Atlanta-based playwright, dramaturg, cultural worker, director. I have a company called Hush Harbor Lab with Amina McIntyre, and we specialize in doing new play development for Atlanta-based playwrights. I'm also the associate artistic director at Theatrical Outfit in Atlanta as well. I'm an adjunct at Clark Atlanta University. All the jobs because I'm in the theatre. So I got to eat.

Leticia: You're like Julius from Everybody Hates Chris. You got multiple jobs and—

Addae: Multiple jobs.

Leticia: I think it's so wonderful because we actually really get to... You get to touch a lot of facets of the theatre world. Truly embodying this idea of a theatre artist. We also want to start [by] asking you, why theatre? There's poetry. There's literature. What about theatre is the mechanism for how you want to tell stories?

Addae: I ask myself that question every day. It's funny initially back in '89, when I left Florida to come to Atlanta for undergrad. I thought I was going to be a filmmaker. I was set on becoming a filmmaker, but I'd done theatre all through high school. I was a performing arts school kid and so that's all I did. And I was like, “I'm done with theatre, I'm going to retire.” And at the age of eighteen, I thought I was going to make films. Literally when I came to Clark, I was a film major. And the first thing I did was audition for a play in my freshman year. But I kept my film major. I later changed it to English and then eventually theatre.

I remember that freshman year, that fall semester, I read Adrienne Kennedy for the first time and I was like, “Oh wow. Oh, this is cool.” I'm like, “You can't possibly stage this though. This is cool. The writing's amazing, but you can't possibly put this on stage.” And sure enough, across the street there's Spelman, there were two professors who were doing Adrienne Kennedy's work, and one of them was Tish Jones. I think Tish ended up going to Iowa after Spelman, but she did a production of The Owl Answers. And I was like, “Oh my God. You can actually stage this play.” That's when I think the commitment to theatre really started happening for me because I'm like, “If you can take a dynamic text like this and actually put it on stage, then maybe there's something to be said about this art form that I want to engage in.”

Jordan: So Adrienne Kennedy, huge fan of her work on this podcast. Yes for you hitting that point here and also there's something about theatre and the liveness and the imaginative qualities going to school and seeing Adrienne Kennedy's work was part of what led you into theatre. What was the spark that led you to pursue this professionally? Was this something that... Was it linear from there where it's like, “Okay, now that I've discovered theatre I'm just on the path.” Or what led you into this as a career path for you?

Addae: I think I was lucky enough being at Clark Atlanta University to have all my professors were working theatre artists. And the great thing about that was that I got a very realistic idea about what being a working theatre artist is. There was nothing remotely glamorous about it. It's a lot of hard work. It's a lot of sacrifice. I think I was blessed to be in a situation where I had these role models who were actually doing the thing. But I also knew that, if I was going to actually do the thing, I was going to have to get an MFA. I was going to have to probably teach. I was probably going to have to do these other things that I wasn't necessarily excited about doing. But I think having those early, professional role models really made me know that it was possible, but it also made me very aware of what the sacrifices are in terms of being a working theatre artist as well.

Leticia: It's rough out here being a theatre artist. I think sometimes, like you said, we lean into the glamorous, like, “Yes, I'm making art.” But it takes a lot of hard nitty-gritty work, and the reality is, for so many of us, we're hyphenated theatre artists. We can't just be a playwright. We also maybe got to dramaturg on the side and we got to be a director. It's a travesty that there's not the investment at least financially a lot in the theatre institution, specifically in the United States—other countries have a national theatre. They see the importance of theatre in a different way than in the United States.

But I think that you are a testament to juggling but also recognizing both the hard nitty-gritty work that goes into theatre and also the fun and beauty of it and the excitement to create in this art form.

You are based in Atlanta, your home base. Jordan is from Atlanta, if you didn't know.

Jordan: “I get my peaches out in Georgia.”

Leticia: And y'all wonder why we didn't have someone from Atlanta on the podcast episode earlier. Your theatre home is in Atlanta. Atlanta has a lot of... not this peach emoji, Jordan.

Addae: Peach emoji.

Leticia: You work in the Atlanta theatre industry. It has a really rich, rich history and culture, and some people might not know it's a place where a lot of theatres being made compared to other, more recognized industries: New York of course, Chicago, DC. Can you talk a bit about what it's like for you being a working theatre artist in Atlanta and how it may differ from places like New York, Chicago, and DC?

Addae: The thing about... I love this scene. When I first came to the city, I fell in love with it. Culturally, it is rich. Historically, it's rich. And the theatre community has a really rich history as well. There are some challenges without a doubt about making theatre in Atlanta. And I think a lot of those challenges are being addressed very directly now. A lot of it is because of the current generation's push to make and to enforce some change in the city.

But for a while, there were at least five or six active Black theatre companies in Atlanta when I first came here in the late eighties, early nineties. Not as many now because just the nature of maintaining a Black institution anywhere in this country is a challenge. But the thing about Atlanta that I just love, and that feeds me artistically and creatively, is that it's just Black lives. It's a Black ass city and unapologetically so, and I think that's really reflected in the work that Atlanta-based artists create. And I think what I'm pushing for is to make sure that some of those stories and some of that cultural richness is on the stages in the city as well. And not just simply in the music or the other acts of the culture, but that is actually on the stages as well.

Jordan: Yeah. Yeah. I love that. I think that you highlighting a lot about the cultural richness of Atlanta as a city, and also being reflected within the theatre, is something that I know you've been passionate about for a while. And also, I feel that too. I'm from Atlanta, I've lived in Atlanta, I've seen theatre in Atlanta, but I rarely have seen shows about Atlanta in a while in Atlanta. It's really rare to do that and I know part of that is in your own work as a playwright. I believe you recently had a play up around that was set in the time of the Atlanta child murders. Am I correct about that?

Addae: Yeah. We just finished this really, an immersive ritual called Cassie's Ballot. That was definitely inspired by the missing and murdered children's case in Atlanta from the early eighties, which had a huge impact on my life as a child living in Florida. But it is also something that, just now in the city, they're starting to commemorate what happened to the tragic situation of those missing children that happened in the early eighties.

And so, for me, creating this piece—and it is actually an adaptation of our longer piece that I was working on that I haven't finished yet. I really want to think about, and something I've been thinking about a lot in relation to the work that I want to do in my elder years. I'm really interested in creating work and being a part of work that's both transformative and healing, because I don't think we have enough of that.

And we also don't have enough work that centers, Black audiences as well and what they experienced. Those are things that I was trying to focus on when we created this piece, and it was done outdoors. It was immersive. It occurred at the Western Watershed Alliance, which is this community area that has hiking trails. It was a really impactful experience, creating theatre outdoors that totes a Black-centered narrative. I'm hoping to do more work and more of that kind of work in the future.

Jordan: Yeah. Being a playwright with your particular style of writing or artistic vision. Do you feel like that is your oeuvre as an artist? Or where do you draw inspiration from when you're creating these worlds that you write about?

Addae: I've gotten in this thing of saying that I'm just at this stage in my career. I just want to be a vessel, force, and transformative narratives, that's it. I'm like, “Just let me be. Ancestors, let me be a vessel to tell some narratives that folks haven't heard about who we are as a people that's going to transform us and empower us and inspire us.” Because I'm tired of everything else.

Leticia: I think what's interesting to me, and you didn't use this word, but in many of the halls that I have taught in, there's been, at least I've seen this pushback by specifically Black theatre students being like, “Why we always got to do these plays about Black pain?”

Addae: “Black pain. Black trauma.”

Leticia: “Black pain. Black trauma.” And they're like, “What about Black joy?” I think there's definitely a place for that conversation to happen. But often my response is so much of Black life is capturing the both/and of it. It won't be truthful—and not truthful in the authentic sense of it, but truthful—to just be like, “Well, everything's hunky dory.” At one point, me and Jordan were joking, like, “We're going to write a musical called The Black Joy Musical, and it's literally going to be everything but Black joy.”

Addae: Exactly.

Jordan: Oh my goodness. Blast from the past.

Addae: The Black Joy [Musical]. And the thing is, I am all hashtag team Black Joy. But I think, too, that—and you guys are also educators, so you're encounter[ing] this too, especially dealing with Black students not wanting to deal with the hard parts of our history. I think that Black joy of course is important and I think we need more black comedies just like—

Jordan: Yes. And good ones.

Addae: And good ones. We so need that. But also though, too, I think when it comes to this fear or this hesitation about tragic events or traumatic events, I think it's really the job of the dramatist or the playwright to make sure that while we're showing these tragic events, there is this sense of resistance and struggle and possibly even transcendence because the thing with the Black story in America in the United States is that we wouldn't be here if somebody ain't transcend all that mess. I think while it's important to talk about the serious things and the potentially traumatic things, I also want to know how we got over, how we make it to today. And I think that's the thing that might be missing from some of these narratives that I think Black students especially push back on.

Leticia: Yeah, definitely. I think of something like Pearl Cleage's Flyin' West as a great example of it. One, love Pearl Cleage. Is she an Atlanta native? When I think about someone like Pearl Cleage, prolific, wonderful playwright. She has decided to make her home, her artistic home within Atlanta. And I think that is one, not common, right, because I think the drive is always these big markets. It's always Broadway.

We've seen a lot of, specifically Black women playwrights, get on Broadway in these last couple of years, either as bookwriters for musicals or their own plays going up, like Dominique Morisseau. I'm not knocking the hustle, get your coins, get your money—

Addae: All the coins—

Leticia: Get your notoriety. But I think there is something really special about working in a Black city for Black audiences and being so committed to that you dedicate your career to being there. I want to uplift Pearl Cleage as someone who has decided to do that, which is not the common path, at least that I'm aware of, for many playwrights.

Addae: Yeah.

Jordan: Mm-hmm. No, it's not. And also the commitment that you talked about Addae about centering Black audiences. I think that is something that is really important. I remember someone telling me, “There's a difference between Black theatre and Black Lives Matter theatre.” And I'm like—

Addae: Oh wow.

Jordan: Legitimately cannot get it out of my head.

Addae: But when you say that, because I always say that there's a difference between Black theatre and African American theatre. I know, because, to me, Black theatre does center Black audiences. African American theatre, however, I think is really concerned about explaining Blackness to white people. And the thing is, I think it's easy to throw shade at contemporary Black artists who we know do that, but it's also been an issue historically in Black theatre that a lot of plays were definitely written to educate and enlighten white people about the Black struggle. And some of those plays I love, but also I'm tired, I've seen those plays.

Because I don't think that's what Black audiences need. I think one of the challenges that we have, and one of the challenges that we need to address is, as Black theatre artists, how are we actually fulfilling the needs and desires of our people? And I don't think we ask ourselves that question enough. Then we wonder why Black folks don't want to come to see theatre.

Jordan: No. I think you're absolutely right. That historical debate, art versus propaganda. Like you said, this is not a new conversation. Even Leticia has done, and is going to, in the process of doing some extensive research around the NEC [Negro Ensemble Company], and when they started, that was part of the problems. One, why is Negro in your name? Two, why were the first plays that you produced by white playwrights?

One of the founding members of that was a white man. Yes, it's about... Yes, we understand that there's this cross-racial history that comes with Black theatre and Black theatre history. I do think if we don't ask ourselves those hard questions, as you're asking about, [it’s a] disservice to not really question ourselves and it's great that there have been people throughout history that have asked those really tough questions, but it hasn’t made them very popular. Let's just say that.

Addae: That's true. That's true. That's true. It's interesting. I've been going back and just reading some, because thank God for university access and access to Alexander Street Press. I've been reading all... Love me some Alexander Street Press. I've been reading some plays, I was reading these plays by Zora Neale Hurston, which were never produced. And I'm just like, “Damn it, Zora was writing for Black folks even when she was writing dramas.”

Jordan: Yes.

Addae: I'm just like, “Wow.” And again, why aren't these plays being produced? Especially with all these issues and questions we have about what is canon? What isn't canon? What does canon actually mean as it relates to Black drama in particular? It seems that the things that we still want to canonize are things that explain Blackness and Black struggle for white audiences and not things that center Black audiences.

Leticia: Yeah. I think it's interesting. One, I just love this conversation because I'm always curious about where Black audiences fit within Black theatre and Black drama and often where each playwright actually situates themselves in relationship to Black audiences. I think it's interesting now that we're seeing a lot of programs of Black playwrights, contemporary Black playwrights, I think Dominique Morisseau has one, I think, Cullud Wattah—Jordan, what's the playwright’s name?

Jordan: Erika Dickerson-Despenza.

Leticia: There's someone else. I can't remember off the top of my head, but there's these program inserts of rules of engagement... Aziza Barnes, Aziza Barnes. They also do this, rules of engagement of either one stating quite clearly, “This is for Black people and for Black audiences.” And also being like, “It's okay if we do the Black thing that we do, and we respond directly to what's happening on stage to do the call and response.”

I think there are movements to think about even in very white spaces, how to transform that space into a place where at least Black audiences feel invited and comfortable, maybe attending and doing some work on these really, really white theatres to be like, “Why are there no Black folks in here?” This is why we have things like Black Theatre Night, even in a place like New York where there's a lot of Black theatre artists. That you got to have a Black Theatre Night for most of the audiences to be Black. That's wild to me.

Addae: And it's funny because I call it the Black-as-fuck curtain speech because most of the, And then most of these speeches they clearly state it's like, “This play is written in the tradition of the Black Arts Movement and we want audiences to engage, to talk back to the people on stage.” And I think that kind of encouragement makes Black audiences feel comfortable. But also, too, when we think about educating the white folks that may be in the room, making them aware that this is a tradition. This is a part of how we actually craft and create work. This is a part of how we actually process and deal with our realities, this call and response. It also gives them the moment to be embraced and accepted as guests, but very much of aware of the fact that they are guests in this experience.

Jordan: Absolutely. I think that I also love this conversation because I think part of working with you in these different projects we've gotten to collaborate on, is we are thinking about Black audiences and Black spectators or Black witnessing and what that means. And so I'm curious about your own theatre company in Hush Harbor Lab, which I've gotten to work with you all on that and the commitment in that work to centering.

I think for me, it's new work around Black playwrights. Which can often, one: Black dramaturgy is another whole conversation that we could go down the rabbit hole.

Addae: A whole conversation! A whole conversation!

Jordan: And I know that dramaturgy itself is in a moment, but then not having a moment. So anyways, I just would love to hear about the impetus to create a space for Black playwrights to develop new works and there's a lot of rules of engagement that you all have there that I just would love for you to share.

Addae: Yeah. Yeah. Amina and I—having been in a lot of development rooms on plays by written by Black writers and white writers as well, as a dramaturg, as a playwright—I think what we started to notice was that one, there were very few predominantly Black spaces that felt comfortable and felt like family, like you were actually engaged with these people who understood you. You did not have to explain yourself or your process to them, and you can all get together and help shape a world in terms of the piece you were working on.

We had very few of those experiences in our own development experiences, both as playwrights and dramaturgs. And so we started thinking, it's like, “What would it be like to have a new play development company that really focused on a process?” A process that we're still shaping, a process in a way of developing Black plays. Particularly developing Black plays for Black audiences, but also developing Black plays for Black audiences that weren't necessarily social realism or kitchen table realism. Because they love to put Black folks in the past. They love to put us through something that's super-hyper realistic. Where are the spaces for Black writers who don't write like that, but also want to center a Black audience? And there wasn't a space so we decided that we wanted to create that space.

And also two, there's so few opportunities for folks who didn't go to graduate school, who aren't at MFA programs and who were Black storytellers, there's so many things for them to develop their work. One of the things that we're really pushing towards now is like, “How do we get folks?” And this is something I'm thinking about, and even the work I do at Theatrical Outfit in terms of new play development: how do you get people in the room who aren't in graduate programs? Because I think one of the things that's missing from Black drama is non-academic Black voices. That's also something that we're really focusing on now with Hush Harbor Lab.

The whole idea of a Hush Harbor, hush harbors were these spaces, these sacred spaces, deep in the woods that Black folks would congregate to during the era of enslavement. It gave them a safe space to be themselves away from the enslaver's gaze. We really think about what happens when you create or have a space for Black artists to create their work outside of the gaze of white American theatre.

Leticia: One, wow. This next question that we have is a big question, and I think you've actually done it throughout our conversation. But what is the state of Black theatre, and where do you see it going or where do you want it to go?

Addae: We are in a state. Even though I was born in 1971, I really consider myself in a lot of ways, aesthetically, a child of the Black Arts Movement. One of the main things I think a lot of the artists in the Black Arts Movement were trying to do with the work that they we're creating, whether it was poetry or the novel or drama, dramatic literature, is that I want us to create theatre that is as compelling and rich and complex as Black music is.

For me in a lot of ways, Black music is the pinnacle of our creative expression, because all the complexities of who we are, all of our identities are expressed in the music. As an artist, I want something that bumps as hard and is as messy and problematic and engaging as Kendrick's new album. I want that on stage. I want to see that on stage. I think if we want our people to engage in the work that we create, we really have to start thinking about how can we make this as rich and as complex and as intriguing as the music that we create.

Leticia: And it also makes me think of Jordan's work, and specifically the form of musical theatre. We've talked about this a bit on the podcast in the past, but the hostile terrain of musical theatre as a form for Black folks. If Black music is the pinnacle of the complexity of Blackness and Black people, and then we have this form musical theatre where dance, music, and theatre collide, what are the possibilities there? And of course, Jordan, you're doing the good work of showing how Black, specifically Black women creators, are using that form in amazing ways, even in the past. But it just made me think of that. Like, “Ah, is there an untapped potential potentially that Black theatre has not tapped into yet?”

Addae: Ntozake Shange set the blueprint. That brilliant essay from Three Pieces, in that essay Zake said, “I ain't going to create no theatre that doesn't include Black dance and Black music.” And she pretty much stuck to that throughout the cannon of her work, but also Baraka was doing the same thing with his work. Adrienne Kennedy, she would have Archie Shepp compose the music for her plays in her original productions. It's not even a new thing. But I feel like, again, which is why I love y'all and I love this show, if we don't tap into our own history and really understand the full history of especially Black American drama, we won't understand that all the shit that we want to do has been done already. It’s a matter of us uplifting it and incorporating these techniques to the work that we create now.

Jordan: I totally agree. I think that I really... I love that connection between music and theatre. I find music to be one of the most important things just to me in general. I think your question of... I think it's a really great dramaturgical question, and I think that it is really important to consider this thing, this cultural creation of Black music, which is the lifeblood of African American life. And how best to take what you said, the richness of that and put it everywhere. Theatre, yes. Everywhere, literature, film, TV, all of it.

How do we capture what has been so beautiful about that form in all of these different artistic mediums? We have a fun question, or at least we hope it's a fun question, but we know that Hush Harbor Lab focuses on new plays. There's no dream play because that play has not yet been written or it is still in process. But in terms of your... If there's a play that you would love to direct or you would love to produce in some way, is there a dream play that you've always wanted to work on that you haven't had the chance to yet?

Addae: It's funny because I'm actually... So I also work with this group called Working Title Playwrights, which Jordan has been a part of, and Working Title has their new dramaturgical cohort. I'm going to do a workshop session, and I'm excited because I get a chance to focus on a play that is probably one of my favorite plays, and that's The Mojo and the Sayso by Aishah Rahman. And that is a play that I have been dying to direct. I saw a production of it at ETA in Chicago almost twenty years ago. It absolutely blew my mind. That's definitely a play that at some point before I transition that I want to direct.

Leticia: We are so grateful that we get to engage in conversation with you and that we get to have this conversation recorded because we've talked prior about Black theatre and our thoughts. But we actually want to take a moment to uplift you and ask you, what are your next projects? What are you working on? Plug yourself is basically what we're saying.

Addae: So, I am working on a play that's going to incorporate music in some form or fashion. I don't know if I'm comfortable calling it a musical, but it is a play that centers on a group of HBCU students at the turn of the twentieth century who are dealing with ideas of both identity politics and respectability politics. As it relates to a particular theatre program that was started by Adrienne Herndon, and they would perform Shakespeare every summer. And so these students decide to rebel, and they want to do a cabaret show instead at a whorehouse. I will incorporate ragtime and trap music and really deal with the messiness of Black class and Black class politics in the early twentieth century.

Leticia: It sounds like Jordan, we going to have to... Well, that's home for you, but I'm going to have to get on some plane or train.

Addae: Jordan be getting a phone call—part of the process—once I get this done.

Jordan: I've always... I love, when you said trap music, my ears immediately perked up, because I'm like, I always thought, I'm like, “Why hasn't that been...”

Addae: “Why hasn't it been a trap musical?”

Jordan: Yes, yes. We have a trap museum. We got a trap escape room. We got a trap escape room. Where's the trap musical. It's like—

Addae: We got trap brunches, trap yoga.

Jordan: We're trapped, we're trapped. We need a trap musical. In the spirit of our guest, Addae being with us, we want to pass the mic and see if there's any recommendations he might have for our listeners to engage further with either anything you talked about today or other things beyond that.

Addae: Actually, there are and they're all on the floor next to me. Because I've been reading them. This is amazing book of folklore writings by Zora Neale Hurston called The Sanctified Church that I've been going back to recently time and time again. Because I think there's a lot of interesting theoretical things in Zora's folklore writing that can totally be applied to the theatre that we create. That's one thing.

I was talking about music and the blues, and it's a great book called The Bluesman by Julio Finn that talks about the blues as possibly the spiritual music for Hoodoo culture. It talks about ritual and sound and these performance aesthetics too that are super interesting. I've also been revisiting one of my favorite books, Nommo Drama [The Drama of Nommo] by Paul Carter Harrison which I still think is the aesthetics or the poetics of Black theatre. That's one I've been looking at.

I was talking about Moon Marked—I was talking about Mojo and the Sayso and a part of that class that I'm teaching, I'm going to focus on the brilliant anthology—Moon Marked and Touched By Sun, which is hands down, my favorite theatre anthology edited by the brilliant Sydné Mahone, and her essay at the beginning of that book is still a really important reference point for me because it really focuses on the fact that in terms of Black dramaturgy and Black narrative innovation, it's always been the systems. The systems have always been the one that have pushed it. Probably starting with... I would say starting with Grimké but also like Marita Bonner as well. Those would be my recommendations if had any.

Jordan: Yes, those are amazing recommendations. I'm writing about Zora Neale Hurston in my dissertation, and I have not read The Sanctified Church. I need to get on that.

Addae: Get on it. Get on it.

Jordan: Oh my goodness, Addae, I'm so happy that you were able to join us for this episode. This has been such an honor and a pleasure.

Addae: And also got to shout out y'all, because y'all doing that my grandma would say, y'all doing that “good colored work” out here these podcast streets. Because your podcast has been so helpful for any of us who are teaching African American theatre. It's been a wonderful contribution and I just want to encourage y'all to keep doing it, keep doing that good colored work.

Jordan: Thank you so much. That means so much to us. Well y'all, we have so many more episodes coming up this season that are hopefully going to blow your minds like this one is going to so please stay with us. We have so much exciting things coming up. Thank you again to Addae for joining us today. And we'll see y'all next time.

Leticia: This has been another episode of Daughters of Lorraine. We’re your hosts, Leticia Ridley—

Jordan: And Jordan Ealey. On our next episode, we'll discuss the life, legacy, and work of Micki Grant. You definitely won't want to miss this. In the meantime, if you're looking to connect with us, please follow us on Twitter @dolorrainepod. P-O-D. You can also email us at [email protected] for further contact.

Leticia: The Daughters of Lorraine Podcast is produced as a contribution to HowlRound Theatre Commons. You can find more episodes of this series and other HowlRound podcasts in our feed on iTunes, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and wherever you find podcasts. Be sure to search “HowlRound Theatre Commons podcast” and subscribe to receive new episodes.

Jordan: If you loved this podcast, post a rating and write review on those platforms. This helps other people find us. You can also find a transcript for this episode, along with a lot of other progressive and disruptive content, on howlround.com. Have an idea for an exciting podcast essay or TV event the theatre community needs to hear? Visit howlround.com and submit your ideas to the commons.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here