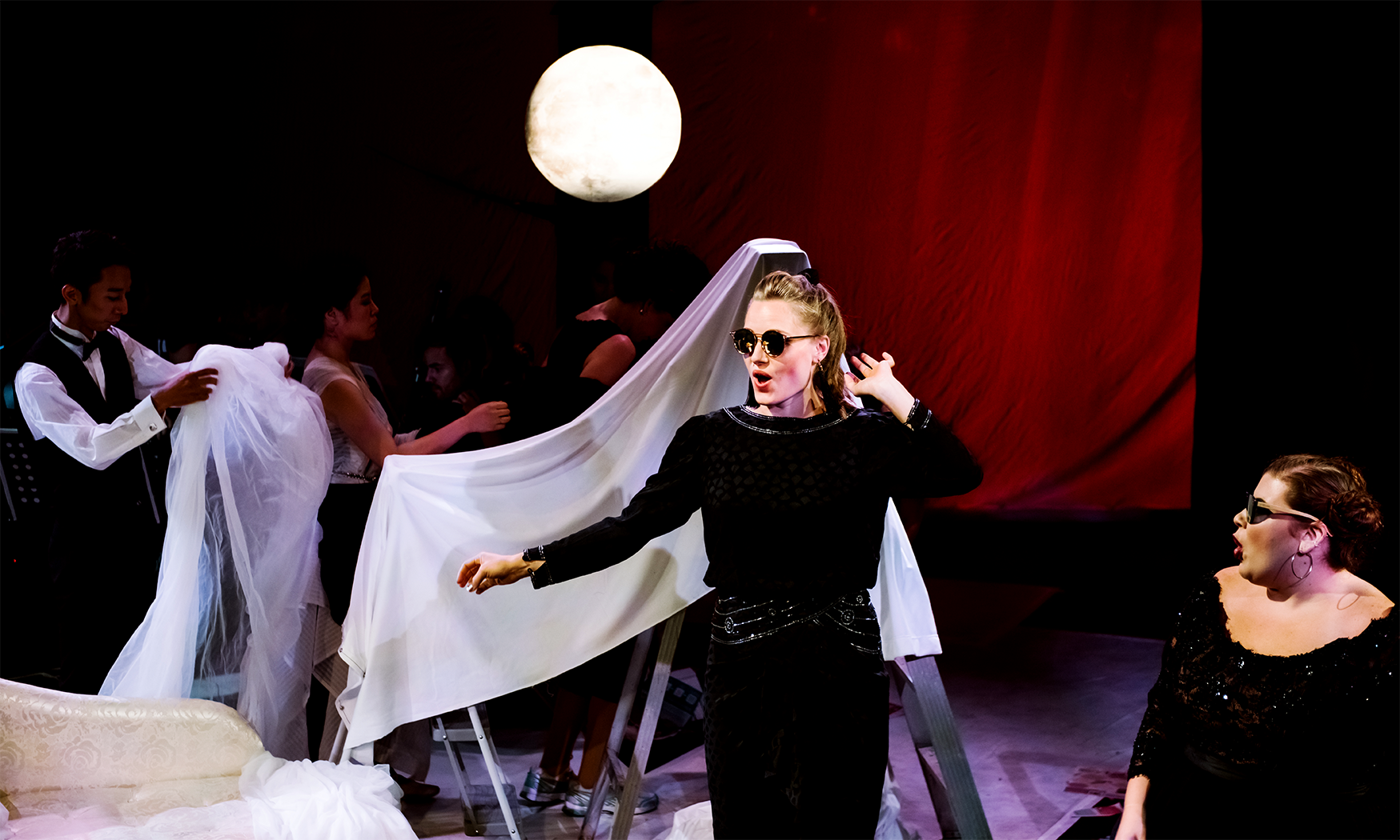

The floor was quite full already, with the orchestra set onstage. A viola, violonello, flute, clarinet, bassoon, keyboard, and two violins were separated from the singers only by the arching black silhouette of a tree. Budnick as conductor, in silver sparkling heels, stood before them like a commanding fairy, guiding her young and capable musicians in their magic-making. Two ladders served as bookcases, entryways, trees, and whatever else the actors needed as they moved between settings. Ladders were a clever choice; they helped create levels without obstructing sightlines. Metaphorically, they reference the social climbing of the stepsisters [Aurora Martin as Noémie (covered by Kristin Lawler) and Katelyn Thompson as Dorothée (covered by Sarah Klopfenstein)] and stepmother (Suzanna Guzman, and Christine Field Sinacola on alternate days) as well as Lucette’s demoted social status. Rather than forgetting altogether that I was watching an opera, I felt that I was party to this make-believe, watching the musicians under Budnick’s wand and smiling at the ingenuity of a carriage made from seven servants.

I was not alone in enjoying the meta aspects of this production: when a forest spirit (part of the fairy godmother, or La Fée’s, tribe) climbed the ladder on stage left and turned the moon around to reveal a clock, the audience cooed in recognition and delight. This clever set piece was rich in the type of metaphor Pinkola Estés explores in Women Who Run with Wolves. The moon is in fact a time tracker, one that relates directly to women’s cycles, whereas the twenty-four-hour day, which rules our clocks, relates to the male cycle. Uniting the time measurements of the moon and the clock is deeply poetic, uniting the masculine and feminine, and calling upon time’s relativity. For Lucette and Prince Charmant, one night apart may feel like a month, one month together like no more than an hour. Lucette, like many fairy-tale damsels, is on the cusp of womanhood; her transformation comes to its full fruition when she dons her ball gown, which is silver on top but dyed red from the hips down. Liam Corley’s lighting design emphasized red tones, furthering the show’s visual connection to a woman’s cycle.

La Fée, in paint-spattered jean overalls, waved a long-handled paintbrush from atop a silver ladder beside the moon, directing the forest spirits to her whims.

Corley also drew from “Vasilisa the Beautiful.” In that story, night and day are brought on by horsemen who gallop through the woods; the Black Rider carries night, the White Rider the moon, and the Red Rider sunrise. Cendrillon’s costumes and lighting used this stark color palette, which is so deeply archetypal (in Snow White, the Queen wishes for a daughter with hair black as ebony, skin white as snow, and lips red as blood). In this version, the stepsisters’ feet were not sliced to fit into the shoe, but the employment of primal colors referenced the possibility for violence inherent in fairy tales and in transformation.

It was hard to dislike the stepsisters and stepmother due to the sheer fun Martin, Thompson, and Guzman provided. Apart from leaving Lucette at home when they prance off to the ball, the stepsisters do not directly torment her in this production. I suspected that if the overbearing stepmother left for a few weeks, Lucette and her stepsisters would be swapping clothes and sharing secrets. Martin and Thompson were perfect compliments in their soprano and mezzo-soprano roles, echoing their mother’s sentiments in unison, bickering with each other, scrambling for the spotlight, and falling in line more awkwardly than Madame de la Haltière would like. Martin’s haughty Noémie high-stepped like a baby giraffe learning to walk. Thompson displayed an acrobatic acuity for slapstick and clownish expressions. Guzman, as the leader of this pack, commanded with authority. She tickled the audience with impeccable comedic timing, knowing just when to arch an eyebrow or deliver a knowing smirk.

The inventive, resourceful costuming by Rachel Belleman and Lizzie Milanovitch reflected the hard work of maintaining Madame de la Haltière’s household. Transmutations within a stark color palette of black, white, and red turned performers into servants, fairy spirits, and nobles. The gauze and black fabric used as set dressing also helped transform characters in the blink of an eye. Lucette wore a black-and-white patchwork skirt that could have been sewn from scraps of leftover cloth. Sulgi Cho as La Fée (covered by Trysten Reynolds), in paint-spattered jean overalls, waved a long-handled paintbrush from atop a silver ladder beside the moon, directing the forest spirits to her whims.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here