Florence Foster Jenkins

The Unlikely Soprano

Stephen Temperley’s Souvenir: a Fantasia on the Life of Florence Foster Jenkins, is a tender send-up of delusional self-belief. The British playwright sets the action in 1964, nearly two decades after the death of the New York heiress and socialite whose absolute lack of musical talent was no hindrance to her will to be heard. She became famous, holding concerts where she performed the most difficult works of opera with an extraordinary and astonishing lack of skill. She even filled Carnegie Hall. People came to laugh.

Her story is told through the eyes of her pianist, Cosmé McMoon. The two-character play, with a set requiring only a piano, a table, and two chairs, is economical to produce yet satisfying, making it one of the most produced plays in the United States. It’s a good choice for 1st Stage, founded six years ago in the burgeoning DC suburb of Tysons Corner by two former public school teachers and an acting and voice teacher. The production couldn’t have been better.

The play opens in a Greenwich Village supper club. Cosmé, rendered convincingly by Brian Keith MacDonald, is reminiscing about his twelve years as Ms. Jenkins’ accompanist. “People used to say to me, ‘Why does she do it?’ I always thought the better question was, ‘Why did I?’” Cosmé, after all—a young musician and aspiring song-writer—can hear that Jenkins (wonderfully played by Lee Mikeska Gardner) is horribly off-key, a fact she herself is blissfully ignorant of and, when pushed, vehemently denies. “There is nothing wrong with my ear,” she fumes at Cosme. “I am known for my ear!” Cosmé takes on the work to pay his rent. Another reason, too, propels him. “She was so absolutely, transparently sure of herself. Like a child. I found it touching. I wanted to protect her.”

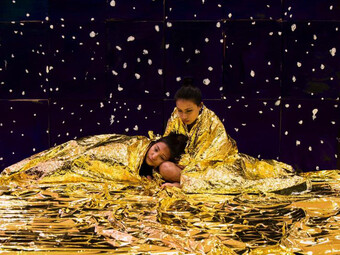

MacDonald as Cosme McMoon. Photo by Teresa Castracane.

She is endearing, in spite of her self-delusion. Her indomitable pursuit of her art, her insistence, her hard work—all are admirable, though misguided. She admits that one of her worst fears used to be that she would be ridiculous. She has overcome that fear and is blind to the fact that audience members at her concerts are stuffing handkerchiefs into their mouths to stifle their laughter. “When I was a child,” she tells Cosmé, “my singing was actively discouraged. It was music that saved me. My whole life has been in preparation for this.”

“Her folly,” as Cosmé puts it, “was so stupendous you had to admire its scale. Like the Chrysler Building.”

He tries to ensure that her concerts are given only at the Ritz-Carlton, where she has a suite; he wants a crowd that is small and polite. But Florence has bigger ideas. She wants to cut a record. Cosme tries to dissuade her—“Suppose what you hear is not what you expect?” Again, Florence with her courage and can-do attitude, prevails: “It is from our greatest challenges,” she gently explains, “that we learn the most.” The record is made. Listening to the record (part of the actual record is played during the production and is unbelievably bad), Florence pinpoints one little passage in Mozart’s Queen of the Night that doesn’t please her, conceding, “There is something that is not quite right.” She resolves to record those few notes over again. And she goes on to make more records.

The production, in the hands of Jay D. Brock, is beautifully directed and wonderfully cast. The tenderness between Cosmé and Florence is palpable. Lee Mikeska Gardner creates a well-rounded Florence: warm, lovable, dignified, and clueless. MacDonald’s Cosmé is endearing and believable. The slender quality that can dog two-character plays is absent here; the stage feels well peopled. The audiences attending Florence’s various performances are skillfully evoked (sound design by Gregg Martin) and the costumes are fabulous. Designer Yvette M. Ryan clothes Florence in garments that match her eccentricity yet manage to convey her dignity, as well. During her performance at Carnegie Hall, Florence changes into various costumes, one for each musical piece she performs. The costumes are surprising, playful, beautiful, and absurd. Stage manager Tammy Hunter must be quite skillful. She keeps the changes lightning quick and the transitions admirably smooth.

Backstage in the changing room, the performance at Carnegie Hall now over, the most touching and tense moment of the play unfolds. Florence, shaken and tearful, asks Cosmé why the audience laughed throughout her performance. He tells her it was because they were overwhelmed with emotion. They laugh. He has to work hard to reassure her but eventually he convinces her that the audience adored and her performance was wonderful.

Temperly and Matalon were not whimsically taking liberties with the truth; they simply did not believe it likely that Jenkins, so resilient all her life, would suddenly take stock of the audience’s response and allow it to destroy her.

Florence Foster Jenkins is widely rumored to have died of a broken heart—her heart failed a month to the day after her performance at Carnegie Hall, where the raucous laughter of the audience had been impossible to ignore, nearly drowning out her voice at times. In an interview, Vivian Matalon, a British director who first suggested to Temperley that he write the play, explains, “The play itself has never purported to be a factual documentary of Florence Foster Jenkins. Hence the title, ‘a fantasia on the life of Florence Foster Jenkins.’” Temperly and Matalon were not whimsically taking liberties with the truth; they simply did not believe it likely that Jenkins, so resilient all her life, would suddenly take stock of the audience’s response and allow it to destroy her. Thus, as Cosmé recounts, Florence had a heart attack in a shop where she had gone to buy more sheet music, set on preparing for another performance.

While gently parodying the can-do attitude America fosters, the play ultimately is a love story. Cosme’s growing tenderness and respect for Florence and his willingness to accompany her, despite being ridiculed by his musician friends, is carefully fleshed out, along with Florence’s deep trust in and dependence on Cosme. The most prominent love story, though, features Florence and her inalterable love of her art, however poorly matched by her talent. Cosme returns, refrain-like, to an assertion of Florence’s as he reminisces, a credo he, too, adopts: “What matters most is the music you hear in your head.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here