Democratizing Rehearsal

The director of Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production, Will Davis, is himself a trans man with a theatrical practice that is intentionally non-hierarchical. While Everybody is inclusive by design, Davis’s approach to casting is always one that invites actors to be participants in shaping his interpretation of the play. Describing how he runs auditions for a classical play, Davis said he asks actors to choose which role they want to read for. “If I see ten humans who are all very different from each other,” said Davis, “and what unifies them is that they all see themselves as, for instance, this dad character, then I’m going to learn so much more about the play from that process than if I were to see the ten people who were all slight variations of each other.”

In his non-hierarchical rehearsal practice, Davis is more curator than commander. He is interested in “allowing the individuals in the room to self-identify,” while his job is “to create a world where that is lifted up.” Because of the mid-play lottery, Davis had to rehearse each of the roles in Everybody with each actor, in as many combinations as he could make time for. This meant all five actors were teaching Davis and each other about the characters throughout rehearsals.

His directing process deliberately makes space for the expertise and experience of the actors to shape the production. He doesn’t believe actors should “disappear inside” their role, but should instead co-exist with their character on the stage. “It feels violent to me,” Davis said, “that you would ask an actor to ‘pass’ as another character”—whether it’s asking a non-binary actor to play a role as cis or enabling an actor to inhabit a physically or intimately violent character under the excuse of method acting.

It never felt to me—a non-binary person watching from the audience—that these abandonments were motivated by prejudice.

Breaking Boundaries

On the night I saw Everybody, the transmasculine non-binary Latinx actor Avi Roque pulled the roll of Everybody in the lottery. Friendship greeted Everybody with a brotherly hand-slapping handshake; the characters Cousin and Kinship joyfully welcomed Everybody as their family.

The play’s plot revolves around how Everybody must die, and how Everybody may bring someone with them, if they can find someone who will agree to dying as well. And although all of Everybody’s friends, family, and even worldly possessions forsake them on this journey, it never felt to me—a non-binary person watching from the audience—that these abandonments were motivated by prejudice, but rather by the ordinary fickleness of humans (and inanimate objects).

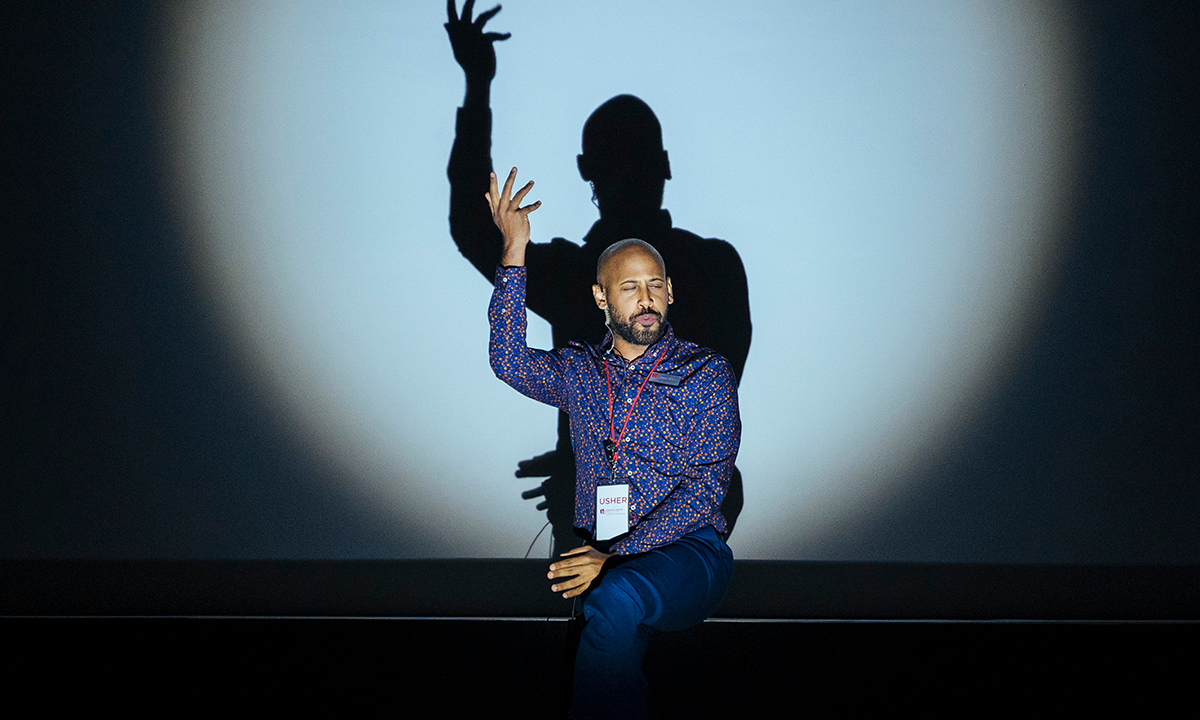

Towards the end of the play, the character Love demands that Everybody strip down to their underwear and run back and forth in front of the audience, repeating, “I AM ANGRY! AT MY BODY!” “I AM ANGRY! AT ITS CHANGING!” “I DON’T LOVE! CHANGING!” This is supposed to be a humbling moment for Everybody. They have forgotten about Love, even though Love has been sitting in the audience the whole time. In retribution, Love literally says to Everybody: “You could humiliate yourself a little more.” But Roque described the scene as a simultaneously “empowering” one, and it showed. “My body, over the span of the last two years, has gone through a lot of changes,” said Roque. “But these are intentional decisions that I have made for myself to find more love and peace with myself.”

Standing at the foot of the stage, barefoot and in boxer briefs, scars in full view, Roque’s trans Everybody breaks the fourth wall wide open as they race, panting, across the carpet. At the same time as Roque’s personal human experience is visible in their character, they speak to a universal human experience as well. “I HAVE NO CONTROL,” they shout, at Love’s instruction, “THIS BODY IS JUST MEAT,” “I SURRENDER.” The room goes dark; giant skeletons twisted from balloons take to the stage, puppeted by the rest of the cast in a disco-lit danse macabre, and Everybody returns to the stage in a hospital gown. Roque remarked that, even while they have made changes to their body, “I’m also just a human being in this meat suit, going through life with struggles and victories, and eventually I will die, like all of us will.” Without concealing what makes them them, Roque as Everybody connects the audience viscerally to the shared human condition of death.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I watched the play on Youtube. It is truly awesome like geometry dash scratch. There’s never a dull moment (except perhaps during the presumably scripted blackout scenes which felt gimmicky even in this context) and knowing that the actors may be playing a role for the first or second time lends a spontaneity that keeps the show fresh.