Friday Phone Call # 66

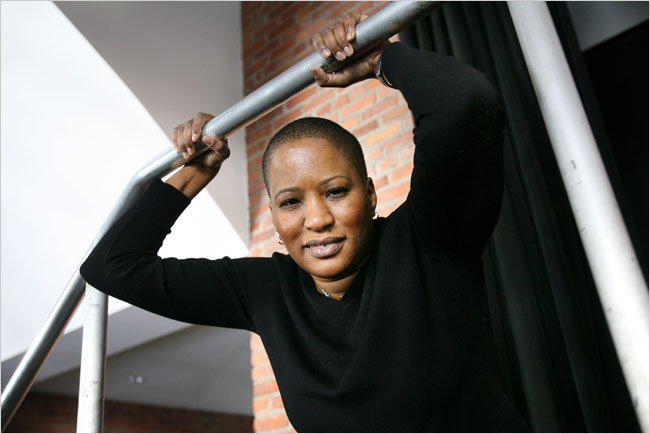

playwright Tracey Scott Wilson

Today my guest is Tracey Scott Wilson. Her play Buzzer recently closed at The Goodman and she's also a writer on my favorite television show The Americans. Tracey and I have, for years, had these wide ranging conversations about the state of race in our lives now – as it is refracted off our experiences of the culture. We go all over the place here as well: The Obama Presidency, The Donald Sterling Moment, The World Social Forum, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and her plays. We reference The Case for Reparations (Coates), Noah Millman's response in the American Conservative, and an episode of This American Life called Housing Rules. What becomes evident to me, as we are talking, is that Tracey is writing her plays from a very particular and personal point of view: she's trying to write out of a question of "why does this make me feel uncomfortable, and what can I learn if I stay in this discomfort rather than push it away?" The difference between what we are supposed to say and feel, and what we want to say and actually feel is her playground. I enjoy playing in that park with her.

David Dower: Hello, Tracy.

Tracey Scott Wilson: Hey David.

David: So my guest today is Tracy Scott Wilson, playwright just closed a run at the Goodwin that we're going to talk about, Buzzer. But then also, a writer on The Americans, my favorite television show of the moment. I'm a politics junkie and that's my era. So, welcome and thank you for making time.

Tracey: Thank you David, I'm really, really happy to talk to you.

David: You and I have this history of talking about race. And you know we often kind of shock each other or explode in laughter so that might happen. You said and I won't repeat it here, you said and still one of the best lines I've ever heard about the way white America was reacting to the Obama candidacy in the beginning. And I keep it as my little private gift from you.

Tracey: Okay.

David: But actually, let's check in ... how are you feeling at this point about the Obama presidency and how the America is dealing with it?

Tracey: Well, you know, personally he's done some things I've found disappointing. It happens with any... you know—

David: That was, you know, mm-hmm[affirmative]

Tracey: You know that was inevitable. You know, we were just so high over the historic nature of it and just wanting the change from you know, Bush. But, you know I feel like history will you know, judge him and prove that you know, I think the things in the right column will outweigh the things in the wrong column. But you know, I just think that it's just complex and you know—

David: Things seems to have moved, and the conversation seems to have moved pretty far. There's been like some permissions, I guess that some, I guess that we were just talking about ... the reparations article, and a few other pieces of the conversation. I remember watching the election returns this time around in November and the kind of shock on the faces of the Fox pundits like what happened to America? Why weren't they in charge anymore? And realizing okay so it's maybe some of the policies are disappointing to me and maybe some of the programs or the progress is disappointing but there's a whole other level in the culture that is just inevitable, it's undeniably moving or at least in my direct experience ... my conversation are moving as a result of this change.

Tracey: I agree completely. I mean there's this ... I think that's probably a lot of, where a lot of the hysteria is coming from. You know, the media also likes to focus on the most extreme statements made—

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Tracey: I just think there's this idea of identity that is really messing with people's heads. And, his re-election really ... the fact that this woman, an anomaly or a freak accident ... you know, I think there's a lot of people who are really just scrambling to hold onto this idea of what they had what the United States means. What our reader should look like?

David: Yeah.

Tracey: And uh, yeah I think that is causing to have a lot of childish conversations and causing people to say, enough with this talking in code. Let's really say what we're talking about. You know the code language is just not working anymore.

David: Yeah, yeah. And to what extent does Buzzer come out of that for you?

Tracey: That was actually sort of a, a reaction actually to the Obama um, presidency. And, you know this whole, you know ... especially when he first ran, you know, people] so he had a huge impact on his election. And you know, sort of this idea that you know, these kids who are all sort of, you know, Jay-Z and Beyonce are the biggest stars in the world ... and you know, uh, that there was this post-racial, you know that race didn't matter. And, but what I actually, one of the challenges ... the idea that just because she doesn't feel, people just didn't have the language to discuss race. Because the language that their parents used obviously was getting more and more irrelevant. So that doesn't mean the discussion was happening.

David: Yeah.

Tracey: And some of the same fears and the same stereotypes and the same anxieties that their parents had and their grandparents had are still there. Because we just didn't have the language to discuss it. I think. So, both of us sort of attempted to look at that.

David: Yeah.

Tracey: You know.

David: It's interesting because the ... I think, so much about language and obviously we're talking about playwrights. But, and even I guess, you're dealing with the language of television ... you're writing about the 1980s on The Americans and I guess ... I wonder, are you having to sort of code switch or language switch to write that play based differently from writing something like Buzzer? You know, to write the television show as opposed to writing something about contemporary America.

Tracey: Well, it's sort of funny. It's actually, because you know we have these characters who are undercover spies, who are Communists and you know, they're coming up against mostly you know, Reaganites and through that whole era ... it's actually the language that we actually, I find I'm actually able to use clearer language because the ideology is so strong—

David: Yeah.

Tracey: You know so um, it's like our communist, our main characters are talking about class and they're talking about races as a way that the story... it's very sort of, very clear.

David: Yeah.

Tracey: Very opinionated because this is what they believe and this what they were brought up to believe. And so, it's actually having a talk about class and race in a way that's actually talking about class and race as opposed to talking about [or all the coded language that was thrown out at the time.

David: Yeah, yeah.

Tracey: So, when actually when discussing ... our characters are talking about it, it's actually quite clear what they're talking about. There's no code.

David: Yeah.

Tracey: There. You know? Um, so it's really interesting.

David: And what are the ... when you're writing for the Theatre now are you having to write in code? Do you see a kind of code holding sway in the Theatre at the moment? Or are we breaking that up?

Tracey: Yeah, I find um, just one of those ... my own work first is ... you know, I'm just wanting to talk about it in a way and through relationships in a complex way as opposed to the you know, I don't want to be didactic or ... you know, it's all about the relationships we're trying to have with each other. And it's not about sort of the singer that we think, because you know, what I find is frustrating through the culture is that everybody knows the things that they're supposed to say. And everybody knows the things that they're supposed to think. But what happens with that is in conflict with how you feel. So that's what I'm trying to get at and that's what I'm trying to, define the language for that. It's, so I'm always ... always trying to move beyond the quote in quote issue. And try to see how people actually look in relationships with each other. You know, I just find in the culture ... it all becomes about this ridiculous name calling.

David: Well yeah.

Tracey: Like, yeah. The Donald Sterling nonsense and who used the n-word and who doesn't use the n-word? And who says, you know, and who says something you know, it sort becomes all about, "I got you now." You know, it's just like the whole Donald Sterling thing. And you know, where was the f-word when they found out he was discriminating in his housing projects? It's like when the same thing more complicated will be on sort of simple name calling and the world sort of doesn't know what to do.

David: Uh-huh.

Tracey: Or what to say.

David: Yeah, yeah. Unless they come screaming out into the media like that, they're not going to like ... you're not going to be forced to deal with 'em. They're not gonna be dealt with. I mean, even though people knew and I'm sure there were articles in the local press in Los Angeles at the time and certainly probably activists in Los Angeles were trying very hard to make a stink about it. I don't even know but I can't imagine that that stuff happens and doesn't register with anybody but the victim. That there's something about the fact that it hit the news media in the way that it did. That was the only reason that anything happened.

Tracey: No, of course. And you know, I mean, as you can point out he was days award from getting an award from the NAACP. You know, you know what I mean? I mean, it's almost funny if it wasn't so sad. And you know, I'm just so ... I actually, I am so sick of this whole you know, n-word nonsense ... I'm so sick of people with ... because you know, that is ... I'm just sick of this name calling nonsense because I don't care. You know, I don't care about someone saying the word, not saying the word or you know, because the issue is so much more complicated right now. And it's, you know, it's always been more complicated than that. You know? It's never been about the bathroom or water fountain, it's always been about econ—, money and power.

David: Yeah.

Tracey: And who has it. And who has access to it. And who was keeping access from that. You know what I mean? And as we get more and more caught up in this language of who says what, of course people are getting more and more savvy. And they're not gonna be caught saying this stuff even in private conversations. But where does that leave us? Still. Still we could say, these are very complicated problems.

David: Right.

Tracey: You know?

David: Yeah, I mean I thought actually ... I don't know how you felt about it, Mark Cuban then immediately after he tries to say something about how this ... sounds to me like what he was trying to say is very similar to what you're saying is that ... are we reacting to the right thing here? And he trips and reveals some kind of you know, shortcoming in his own ... shorthand in his own codes here, around ... you know, he's talking about a teen in a hoodie and everybody goes off on that phrase. And they don't deal with the underlying question of, what is Cuban trying to say about how he feels personally? About what's happening in this moment. Like that's actually what's interesting to me. To hear more about how he felt and how he put that together. But we couldn't get there because he used this other thing and that thing went ... that's what became that story. You know, in—

Tracey: And I'm, uh, it's ... I find it extremely frustrating. You know, that so much is getting reduced to these incendiary statements. You know what I mean?

David: So how do you write about that as a playwright then, Tracey? How can you take that on? Because that is kind of language ... with codes and all the stuff that you're talking about and the difference between how people feel personally, you know, privately underneath this ... you know, what's supposed to be said and what is supposed to be felt. How do you actually manage that as a playwright? What are your ... what are you finding trying to do it?

Tracey: I mean, I just feel like you can't reduce people to the thing that they say in the moment of anger or weakness. You know, I think that, I feel like you know, often times if the Donald Sterling thing was a play ... you know, the problems in the play would be screaming actors, girlfriends, on the phone. You know what I mean? Or you know, that would be the sort of the play would end. You know, and then that's exactly the way that it is in the culture. It's like, "Oh my god, Donald Sterling said this thing. We're gonna take this team away from him." But yeah, he's gonna make two billion dollars regardless, you know what I mean?

David: Exactly. You won't feel good about taking his team away from him.

Tracey :Exactly and he could buy a hundred more housing projects in which he'll discriminate. You know what I mean?

David: Right.

Tracey: And so what? So what? Are you really hurting this guy? I don't think so. You know, and so it's just like—

David: And it goes the other way too like, I think about good negro and all of your struggles to get that play right and get people to understand what you were trying to say and all of the kind of, you know concern about, "Oh can you say this about a character who's based on Martin Luther King?" It's not, this isn't really fiction, you can't actually ... can you actually expose these words? So there's the other way of deifying people unable to take their complexity as well right? I mean you ... or am I overstating that? Isn't that part of the challenge you had in getting that play done?

Tracey: Oh no, I think so too. This whole notion of um, in civil times ... what ... who you can, what you can say about people and how much of that humanity are you allowed to see? You know? And it's ... you know it's so funny, just coming back to ... this little moment on TV ... I really love Louis C.K. and his show, Louie. And there was this ... it was a smallest moment, I mean it couldn't be ... smallest moment where he was on a bus with his girlfriend's, his daughters ... and this black guy, this guy who happened to be black I'll say, spit on the bus. And Louis says, "Hey, stop. Don't spit on the bus." You know, that's disgusting and then the way he turns around the bus driver gets involved and the guy ended up blaming Louis for spitting on the bus ... and me and my friend were watching we're like, "Oh my god, this is the clearest indication that Louis C.K. has no problem with race." Because most of the time, that guy would have been a white guy. Because they would have been like, "Oh, we're afraid if we use a black guy we're gonna be saying something." But in Louis it's just like this guy who was a jerk, it didn't matter if he was black or white.

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative]

Tracey: You know what I mean? It's sort of ... yeah, and I just think that that ... that was just one of the most refreshing things I've ever seen. That little small moment. Um, because the idea that you know, you can't cast someone ... you couldn't cast or you couldn't show them as violent or whatever, as an asshole or a jerk if they're black because you would just assume that that's how ... that that's what a black person is.

David: Right.

Tracey: You know what I mean? It's almost as if that person is not acting, as if that person is not ... can't be complex because if they ... because otherwise, you know, it's sort of like, I'm afraid am I racist right now? Looking at this. What if ... you know what I mean? It's like people are afraid of the feeling. You know, afraid of the feeling that it will bring up in them. You know, the fact that Martin Luther King Jr. had numerous affairs, does that take away from anything that he's done?

David: Right.

Tracey: Does that take away? And if you feel that way, then okay let's go there. What does that make you feel? As opposed to just so afraid of the feelings that it brings up in you. I mean, we're so- fear that can make you feel something uncomfortable. That's not to make you feel something you haven't felt before. You know?

David: Yeah. Why did you come out of the house then if it—

Tracey: Exactly. To me, that's what TV... a majority of TV is for. Is that, you come home, you know, you've had a hard day at work you're tired, you want to turn your brain off. And you can turn on something that's just ... you don't have to think. But if you're gonna get up, and you're gonna get a babysitter for your kids and you're gonna do all this and you're gonna out to the Theatre and you're gonna pay sixty-five dollars or one hundred dollars ... why not just challenge yourself for two hours?

David: Yeah.

Tracey: You know?

David: And it goes both directions too. I mean, it comes from both directions. I know, so many of my ... probably friends who are writing African American stories are struck from both directions by what they're allowed to say. And I watched you with the negro, and you got it from the black community and you got it from the white artistic director community. And you got it from all different sides about what you're allowed to write. And whether people were gonna call it that or not, that's what they were saying. Even if it was sort of dramaturgical kind of advice about what's gonna make a compelling character as opposed to you know, people talking about whether you're defaming someone by talking about those things. There was a tremendous amount of pressure coming around what was permissible.

Tracey: Yeah, I have to say I was surprised a lot of the pushback came from making the clan guy, Roe, giving him humanity. There was a lot of, I got actually a lot of pushback about you know, the fact that I um, you know, in the last scene of the play that you know, there was so much giving to—and I got a lot of notes about ... it's just get rid of him. Let's just get rid of him now. And you know, I just think that's part of the issue because you know, these people that you know, that we see in these archival civil rights movies ... these, racists, you know these characters ... a lot of them are still living. You know, they have families, they had ... I mean, looking you know, I'm trying to ... the biggest challenge is looking at those guys as more than just a bunch of stupid hicks in wife beaters.

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative]

Tracey: Because, it was more than that. And really looking at the complexity of the racism in this country. Looking at it now from a ... you know, on the ground, but looking at it from an institutional level. Uh, I think that's when people sort of recoil because it's like um, you know, not wanting to look at the sort of, the casual ... or the more um, or the less uh, less violent racism.

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative] You know, we're dealing with this now here in Boston, you know I guess we've been dealing with it. But I've been attending conversations around it more recently because we're hitting the fortieth anniversary of the Busing decree here. And, people are starting to talk ... or at least, I'm starting to find myself in conversations about well, where did that even come from? You know, why was there a busing decree. There was a busing decree you know, because black families in Boston wanted access to equal education and there had not been any you know, sustained efforts ... in fact, you know, many people will say there was a sustained and willful commitment to breaking the law and not you know, desegregating the schools. And so, the busing decree was a result of that. A suit brought by black families in the public school system here in Boston.

And that whole history is really, really hard to talk about here. What is taught instead here is Little Rock. So when ... if you're, apparently, I just heard this yesterday ... apparently in the Boston school system, at least up to a point and maybe it's continuing ... I didn't get the actual data ... but if you're talking at all in the Boston Public school about desegregation, you're studying Little Rock so you're talking about it as somewhere else. You don't have to talk about it as complicated ... that it's as complicated as it's in your own history, it's in your own neighborhood, it's in your own building. You know?

Tracey: Right.

David: And that complexity, it's very easy in the Northeast as a problem of the South. And a problem of ... as you know, you say the you know, the hicks and however you described the clan man in that ... story. But, it's very easy to put it somewhere else. It's much harder to unpack it inside you and inside your community.

Tracey: Exactly. And it even talking about it now, you know, I wouldn't charge anyone to listen to anything to ... listen to this is an amazing, this American life about housing, I think it's called housing. And it's about, you know, Mitt Romney's father used to ... he ran it briefly under Nixon, and was completely shut down. Um, because he tried to try housing discrimination to the Federal dollars. And um, every since Nixon shut that down, there's basically no policy for how discrimination in this country. And of course, we all know that where you live, determines everything. It determines the services you get, it determines the school your kids are gonna go to, it determines access. And so, this is still happening. You know, and I think maybe part of the reason they're not teaching that is because this discrimination is still happening very actively. And there are people who are still very uncomfortable as liberal as they are. As much as they, you know what if Obama, who is still very uncomfortable having a large group of minorities go to their school because of what it means for their pocketbook.

What it means for their pocketbook, what it means for their housing. What it means, they're saying for their kids education. And until we look at that, until we look at that, we're not gonna get anywhere. And it's just about looking at that. You know?

David: I think you're talking about an episode of This American Life called, "House Rules." I just looked it up while you were talking from November.

Tracey: Yes.

David: Okay, I'm gonna link it so that people can find it.

Tracey: That would be great.

David: Yeah. So, we could talk about this part all day, so how's this playing out in your own writing or in your own experience of theatre now? We go to the television work as well but really, curious as a playwright ... are you finding, is stuff rushing to you now to write about? Is it easier to write about this stuff now? Or, what happened?

Tracey: Sorry my dog.

David: Hi dog.

Tracey: Well, it's ... you know it's always hard to write a play. Anytime I write a play I forget how to write a play. And then I'm complaining. Oh it's just so hard. Um, but, yeah I mean, like ... I can't, I just want ... I just always try to challenge myself to not say things that people already know.

David: Uh-huh.

Tracey: You know, to not um, ... you know, don't get me wrong, you know, I love Arthur Miller, he's a genius. He's brilliant, let me just say all that first. But, um, you know, it's sort of safe to do the Crucible. Now. You know what I mean? Because you look back and say, McCarthyism is really bad. You know what I mean? And you sort of ... that sort of, it pat you on the head and sort of send you on your way kind of thing. Um, you know, just to try and not make it easy for myself or for anybody else. I try to write something that makes me feel uncomfortable. Because I know if I'm feeling uncomfortable, other people are feeling comfortable because I have no answers. You know what I mean? Just know, that is the part of the problem because we never really ... there's no easy answers because what we're talking about is really looking at the history, the economic and racial history of this country and how they're completely tied together.

You know this country was built on a slave economy and it's still, still built on that same slave economy. Except now its, you know ... legal ... quote in quote, legal workers. You know, who are basically sustaining our food economy. You know, basically being paid ... you know, and it's ... we have to really look at that. What does it mean to have a country that was built on slavery and it still uses those same policies in place in order for the economy to run? That's a hard thing to look at because nobody wants to pay ten dollars for a tomato.

David: Right.

Tracey: What it means is our food prices are gonna go up. And what does that, you know what I mean? And it's just ... and so, pretty much that affects everybody.

David: Yeah. It's so entangled once you start trying to pull at it.

Tracey: That's exactly right, and rather than pull at it we're gonna scream the n-word and then um, and then you know, stop that person and "Oh isn't that a shame?". And go on our happy way. And you know, I'm not saying it's easy for me to look at it either. You know, because when you start messing with people's pocketbooks that's real.

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative]

Tracey: That's real. And—

David: Did you see Marcus Garvey's The Box, when it ran at the Irondale?

Tracey: No, I missed it. I was out of town.

David: It's an interesting piece that he's trying to do there about the prison labor as where did slave labor go? It went into the whole prison complex and so, you know, in his play the people are doing kind of the same work that they would have been doing just now they're doing it in prison instead of in slavery.

Tracey: Oh yeah, a lawyer from the Innocence Project and you know the use DNA to give people ... to get people out of jail, to exonerate people. And uh, and yeah, we talk about that all the time. You know, when you call up Microsoft or whatever customer service, you're actually gonna getting someone in prison. Or you know, people making Christmas lights, you know ... the Christmas lights that we all put up at Christmas time are being made by slave labor in China, you know what I mean?

And it's just a ... you know, like I said, this is stuff that affects, you know it's a domino effect. And I have no answers for that. But I know, that if we don't look at it, everything's gonna fall apart. You know, it's like ... this country yet, once completely. And it will do it again. It will.

David: Yeah. Okay well that's a hopeful note. Thank you for that Tracey.

Tracey: Well, you know but I said ... I just think that, you know, for whatever reason ... this country's ability to change over relatively short period of time is a ... I think that's one of the things that you know, we appeal to people about this country. For such a young country, you know, some of the ability to transform itself. You know, to go from ... to have a black president at this time in our history is pretty extraordinary.

David: Yeah.

Tracey: And so, I do feel like this, this a very valid fight. What's happening now only, not only in this country but globally. Um, is because, it's changed happening.

David: Yeah, yeah. I feel that way and I haven't ... I don't think I felt it quite on the level of quite of this, seismic level of change ... or this, kind of like, tsunami level of change. It's not immediate, it's not present on the surface of my life. But I feel it just surging up through all ... just, all I mean, it's just surging up. I don't know why, maybe it's because of the anniversaries that are coming, fast and furious. And my, now I'm working in international context so we're programmed around the world on stage, so we're looking at many more cultures than I've been looking at. And seeing what's happening in those cultures and you know, programming a film, program some other stories coming in them that aren't necessarily best told through theatre. And what those stories are telling and it's just really ... I feel that there's actual movement and maybe there always was, I wasn't awake to it but I really do feel it now. And I don't know where it's going and I don't know when it's gonna pop to the surface ever. Um, and what that manifestation's gonna be but I think I didn't feel it ... I have to say, I didn't feel it when you and I were in Africa in 2006, it's not what I was thinking.

When I saw the world social forum at that moment and people were saying you know, it's not that another world is possible it's that another world is happening. That was I guess the moment when I started to go, "Oh, I don't actually know what's happening." And on that level. But it was also interesting there, I don't know if you remember ... the things that happened in that trip. But it was really interesting that all ... that this is the world social forum, it's taking place in Africa and all of the sessions were conducted in two languages; English or French. And there may have been another language but they were translated in English and French. And you just got such a clear sense of, "Oh wow, this is the story. The context of the world." Social forum even is English or French.

Tracey: Yeah, yeah, no I agree. I mean, I feel like, you know, this is a you know, I mean ... say whatever you want about social media but what it's, is it's getting access to these stories that have been happening for a very long time.

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative] Social media for sure.

Tracey: We're still gonna react to the most um, to the stories but still, the stories are coming out in a way that they didn't before. And I just think, it's this you know, forcing some of the discussions that were not happening unless you were really invested in finding out about it.

David: Yup, yup. I know that's true for me for sure. Like stuff is popping into my Twitter feed all the time that I would never have found. I mean, I hate to say it but I would not have read Ta-Nehisi Coat's work in general. I found him through my Twitter feed. I didn't know him and that's embarrassing to me but it's true. That's how I found him and that's how I have been reading along is through his Twitter feed and I go find the articles once he starts talking about them, you know? So—

Tracey: Yeah, he's one of the more ... most remarkable thinkers that we have right now. And uh, it's a very exciting to read about him and he's someone that's just, he's just so ... and he's just so honest in our evolution and uh, his thinking, it's just so like I said, a lot of people who read it who normally I don't think, would have. And, um, you know, and I just think he's ... not only him, but his thinking about racism and many of his colleagues as well. You know?

David: Well he seems to have ... he found a voice where he, that allows other people to enter as a dialogue. It's not a argument. It's not a scream-fest. You know, even the conversation ... I mean, obviously there are haters. But, there seems to be, I'm forgetting now, I should look it up. But there was a really interesting response that came from a very conservative writer who unpacked it from his ... we're talking about the case of reparations. Uh, in the Atlantic Monthly.

Tracey: Yeah—

David: But, um, that the response, now I forget where it was ... um, but it was, from the right and it was very much from a conservative thinker who took the same kind of care to unpack it point by point. I didn't agree with all of his points but I appreciated the openness that he entered the conversation. And somehow, that seemed new, you know, like the screaming for maybe a minute, stopped. And a conversation broke out. Um, which I really appreciated.

Tracey: Yeah, no that's what I appreciated. The fact that he's not threatened by other people's ideas. You know, he doesn't scream at other people and he doesn't allow other people to scream at him. But if someone challenges him, he will respond in like ... you know, we sort in any of our ... in those, I mean, in certain or a certain lane ... BBC, but MSNBC, and CNN, and FOX, and all that stuff, it's all about keeping tally. You know, who's winning, who's losing in that minute and you know, I feel like the things that we're seeing now happening, you know, like you know, I remember when you know, the whole Arab Spring when that happened ... and people were you know, that's when I was still on Facebook but people were sort of, you know, rejoicing and all this kind of stuff ... and I just thought, uh, are you kidding? This is only the beginning of the hard part.

You know, this is that, you know, its like you know when the British finally left India and that's when actually all of the real hard part started. Real problems, the real work and you know, we've seen ... I've seen what's happening in Egypt ... and the thing is that once you've uncapped that bottle, of you know, whatever true democracy is, however that is ... once you uncap it, you can't put it back. However much you try. And I think, that's how we look at our ... we look at history and we ... because we're looking at it, we think that we forget how slow it actually was.

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative]

Tracey: You know what I mean? How history is these little, little, little steps. Little, little, and we forget about that because like you said, we just touch at oh, Little Rock Nine, and catch on these little plants and we're just talking about the day to day to day. And how no one could have imagined that we would get to Obama. No one could have imagined that we never get anywhere near where we are now. You know, and then you know, it doesn't up in the media that's constantly keeping tally like that but, change is slow. Always, right?

David: Yeah. Yeah, change is ... yeah, and, and, incrementalism is not the sexiest thing but it's kind of you know, I guess, I chart it on small steps. Otherwise, I mean that's true for me with the theatre in general, it's true for me in the culture that if I waited for my energy to be renewed by one hundred percent, I would never get out of bed in the morning. So ...

Tracey: Yeah, yeah. I mean it's, this is also what I've seen in the New York Times does that ... I love and it's called ... they call it, it's called Retro Report. And they go back on all these stories that they were wrong about. The emphasis on cultureAnd um, you know, it's funny now its like, I mean it's not ... I mean, it's actually really sad when you ... there was this thing in the 80s called ... some sociologist developed this theory with the super predator—

David: Yeah.

Tracey: And basically, it was just like ... it was this ridiculous theory that there was just gonna be these roaming gangs of, of course they were using code, of black African minority males who were literally gonna be roaming around raping, killing, and maiming people. And they were gonna be uncontrollable, it was called a super predator and of course that whole theory coincided with the three strikes laws, the rise in um, the rise in incarceration of African Americans for small offenses. And now, literally the guy who started that is now looking back saying, "I was completely wrong. I completely misconceived all the data." And now he's trying to get reduced sentences and get some of these people out of jail. You know, and now even Newt Gingrich is calling for you know, that we can't maintain this. It's just interesting you know, to me that you know, the hysteria. The hysteria, like ... I think, I think and people ... I mean, it's certainly showing a print with code and something like that ... but, you know, this whole hysteria around media is just ... the conversation is just has to slow down.

You know, and um, I mean, I don't know if that's going to be happening in more mainstream media but you know, I just feel like coaching those guys or starting that conversation.

David: Yeah, and that it has ways to leak out now where it didn't before. Like it has ways to get to somebody like me, where I would not ... I mean, I don't know I haven't been reading the Atlantic Monthly regularly otherwise, so I wouldn't' maybe someone would have pointed me to it. But now, it comes right at me because I'm ... my, you know, Twitter feed in this case is open. And it can get to me directly.

You know, and I think we're finding with that the lid has come off of the hierarchy of what's permissible to be discussed and when you create some space, like a space, you don't know what's gonna come through ... some of it's gonna be of real value, some of it's gonna be brand new, some of it's gonna be old, some of it's gonna be uninformed, all kinds of stuff is gonna come through. But once you take sort of the gatekeeper's lid off of what people can be exposed to, all different kinds of conversations start to jump off. And this is has been a big benefit. But, I mean, but for me personally, I'm finding my way into conversations that I would not have been able to make the time to get into otherwise.

Tracey: Yeah, yeah. And um, I mean I know, you know that there was like some controversy over um, you know, some graduation speakers were rebuffed you know, because of their, from republicans who were ... who were protesting against that and I find it encouraging that all the speakers who replaced these people were saying, "Why is their argument so weak that you can't hear someone else's thoughts?" You know what I mean? I want to hear what Condoleeza Rice has to say. So what if i don't agree with it? That's what's interesting to me ... this whole discussion ... what I want a discussion is ... one of our more complicated discussions, so much of it is about I don't like how the discussion is making me feel.

David: Yeah I love that you keep bringing it back to that.

Tracey: Yeah. I just get ... it's like, I don't like to ... I don't like how this conversation is making me feel. And um, I want to run away from that. You know, so I try to force myself you know, and I usually can't stay there for much long, very long because it's so ... because it’s so hysterical but just to watch Fox News and to hear what they're saying. You know, turn on Rush Limbaugh for twenty minutes just to hear what this conversation is ... and the other reason I can stand is because of course, they're doing the exact opposite, if they can't stand to hear something so they'll just the exact opposite ... you know what I mean? So it just becomes about this ... you have to so, you know how ... as a person try to find more reasonable, conservative figures but ... you know, this low tolerance for feeling uncomfortable is um, I just find uh, frustrating.

David: Yeah.

Tracey: Um, you know, limiting.

David: Yeah.

Tracey: Of the culture.

David: Wow. That's actually, there's your writer's mission statement. Hey, I have a question, as you go back and forth between TV and theatre, what's the experience besides the fact that you get to walk down the street you told me ... that you have to walk to work on The Americans in Brooklyn. What other kinds of experiences are surprising to you about it? Or you know, how's that going to go back and forth between the television world and the play—

Tracey: I'm very, very, very lucky. I'm very, very, very grateful. Because I really love the show artistically that I'm writing for. My bosses are great, my colleagues are great. And I'm very lucky, because I know that's not always the experience playwrights have when they go into TV or any writer has when they go into TV. It could be ... it's a real hit or miss.

Um, but I'm surprised and grateful to how collaborative it is. You know, um, you know, we are writing and rewriting the show together. And we all you know, we all want the show to be as good as it can be, but ultimately, for all the writer's it's not our decision, you know. Our showrunners are so creative and make the decision and so, what I love about it is you don't have to be precious about it. You know, you go to the writer's room and you throw out ideas and you throw out good ideas, bad ideas, in the middle ideas. And sometimes ideas are well received, sometimes it's not. Sometimes the well-received ideas end up being thrown out for various reasons, but what has really taught me in terms of playwriting is to don't be precious about it. You know what I mean? Just write it, and if it doesn't work you just gotta let it go. Or you just let other ideas ... who cares where the ideas come from as long as the final result's good.

David: Yeah. That's so interesting. Yeah.

Tracey: Like, so much of playwriting um, with ... if somebody cares about, you know, whatever ... I don't know. Just in terms of ... anointing someone or not anointing someone or this one's hot, or this one's not ... When you're in the TV when you're with ten different writers you're just, it's like ... you're just a writer.

And it's just less pressure, you know what I mean? I just find it ... I'm surprised on actually how collaborative it is in the most practical sense. You know when you get into ... you know, whatever, the network and the studio ... those are the things that we as writers in a room, don't have to deal with. That's what the producers have to deal with. However, the material gets watered down or not watered down when it goes up the ladder. You know, and it ... but, we're there we're just trying to come up with the best idea. And I just love that about it. And just to not be precious about it because you know ... just, you don't have to ... you just have to be able to take other people's suggestions and to hear what other people have to say and you learn so much from these other writers. You know, and um, that's why I love ... I actually found it as collaborative if not, even more than theatre.

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative]—yeah, it's also things are getting made faster too aren't they? Things are on a shorter track so you don't even have the time even to sit in years of development on a single story. You're—

Tracey: Exactly. Exactly. Because once they start up and shooting, you've got eight days to shoot it. And that's it. And you just gotta get it out there. And you don't have time to you know, sit around the set and talk about filming a scene for twenty minutes because you know, no one ... the studio's not gonna go over time. You know what I mean? And, so yeah, it's just that ... it's almost like a real check for your ego. It's great I think.

David: Yeah. Well, I wanted to fluff your ego a bit because that show is so great and I'm so grateful that it's on the air and that it's so smart and well made. And also, uncomfortable. I am actually rooting, in that show, for people who are literally attempting to take apart my government.

Tracey: Yes, that's right.

David: And I spend my whole hour uncomfortable in that show in the most delicious way.

Tracey: Yeah—

David: So—

Tracey: Yeah.

David: Listen, speaking of going into overtime ... I'm keeping you and I'm keeping the listeners so much longer than I promised. But um, so we'll just have to do some more of this and I hope you are writing for years on The Americans but that it doesn't take you away from the theatre for long because obviously there's tremendously uncomfortable conversations to be written about in the culture.

Tracey: Yeah, and I hope to write some of those and I hope to—

David: Well, let me know when you're getting your Donald Sterling play together because I might have a boner.

Tracey: Okay, okay I will.

David: Alright. Great to talk to you Tracey.

Tracey: Alright, thank you David. It's always good to talk to you.

David: Have a great day. Yeah, I'll wait. Love ya, have a good day.

Tracey: Bye.

David: Bye.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here