These two forms of “live” exist alongside each other, each one using its strengths to tell a story of the struggle to find life’s meaning—one that is separate from the media so deeply ingrained in our society.

Hosted by ArtsEmerson in Boston in January 2019, The End of TV is described as “a quest for connection amid the static.” It tells the story of two people in the 1990s: Flo, an elderly woman living with dementia who is addicted to the QVC home shopping channel, and Louise, a former auto plant worker who meets Flo after beginning a job at Meals on Wheels. The two form an unlikely bond and impact each other’s lives in ways neither they nor the audience expect.

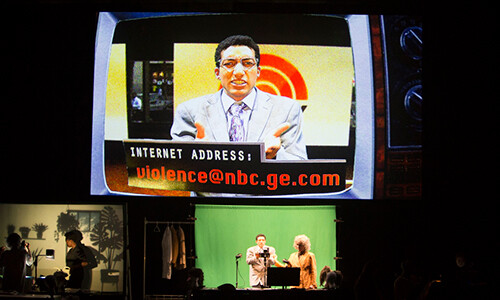

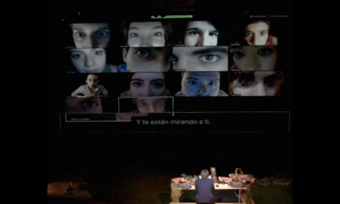

With the help of a blue screen, an overhead projector, a screen above the cast, and a big library of paper cutouts and puppets, director/storyboard artist, Julia VanArsdale Miller, pairs live theatre and live television to create a unique mixed-media experience that speaks to its audience in a profound way. Live theatre happens when performers stand on stage in profile, holding two-dimensional cutouts as props and acting in front of the projector. As for live television, the entire production is projected onto the screen above the actors, accompanied by puppets and slides moved by the actors themselves. These puppets, designed by Lizi Breit, create entirely new characters and settings, but only have a physical presence on screen.

Live television is best used to portray the cable-fueled fantasies of our leads. The way Flo interacts with her TV is immersive: after ordering another new knickknack from the QVC channel, she gets sucked into her television set and goes for drives in the mountains with her daughter and the Jolly Green Giant. The drives are decidedly more colorful than her reality, overshadowing the onstage palette of black, white, and blue with yellow, orange, and green. The sound is also subject to substitution; QVC broadcast audio is muted and replaced by the sounds of a five-piece band. Songs like “Finite Color” and “Reflections in a Hubcap” are beautiful but have an unsettling, slightly uncanny quality to them, which are reflective of the world in which they exist. The music belongs here, but it doesn’t belong in the real world. Nor does the Jolly Green Giant, who is nothing more than a slide on a screen. Flo is later brought back to reality the same way she escapes it—in the middle of a moment and with no warning. She is left to silently crawl back to her house and disregard the foreclosure notice on her door.

Our leads are left with the same things we face after putting down our phones: no escapism, no companionship, no joy. Only solitude.

For Louise, TV shows and radio broadcasts trigger flashbacks to a time when her backyard was in bloom and her father was present. Such flashbacks are given a sepia coloring and a score that, while barely different than previous tracks in terms of structure, is much more musical. Overall, her mindscape reads as more organic than Flo’s, because her memories are derived from the life she lives and has lived. But the flowers and vegetables growing in her garden aren’t really there. There shouldn’t be any music to begin with. These sequences are still just memories, and they can only serve as a brief distraction from the reality she must face below the projector.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here