Confronting Isolation in the Pandemic

In rehearsals since January, the Wesleyan team’s production was disrupted at the beginning of spring break by the pandemic. Once it was clear it would not be performed in person, Pearl, the ensemble, and the production and artistic teams began to etch out plans that would transfer the work to a virtual stage and reimagine it for a new platform. When I asked Pearl if the company had proceeded on some theoretical basis or more by the seat of their pants, she replied, “Definitely it felt like the seat of our pants. We were learning a new medium, discovering what we could and could not do, and addressing the poverty of the situation in a way that then became content for the play.”

Pearl, having been raised by a father who practices Buddhism, is familiar with the principles of nonattachment and nonlabeling, which have steered her towards the kind of theatre she makes today. “If faced with an unworkable space, my response is always to notice it more deeply. Get curious,” she said. “What is actually here that can be of use? How does the obstacle become the opportunity?” No matter the space, Pearl asks how she will be in relationship to it and what’s going to emerge. She had to do the same thing with Zoom to make her students feel safe in the not knowing, and instead be in the joy, the pain, and the presence of saying, “Wow, we are really confused about why we’re even moving forward right now. How on earth can we connect to each other? Let’s just be in this frustration and see what grows out of it.”

As if in free fall, the actors revealed their doubts, confusion, and willingness to be in the liminal between spaces.

Reflecting and Transcending Real-World Concerns

Given the social and political upheaval in the United States since March 2020, one of The Method Gun’s conceits—a rejection of our nation’s systemic injustice, exclusion, and inequality—assumed deeper meaning. This production magnified the issues we’ve faced in the past months of chaos. In fact, viewing The Method Gun a second time, in light of the George Floyd tragedy, revealed how well the play echoes the American society. However, to focus on this alone diminishes Wesleyan’s achievement in using Zoom to find, in Peter Brook’s words, “the vital currents hidden in this misery.”

The ensemble adapted their original devised text to explore the more profound questions of isolation and of nonattachment to certainty. As if in free fall, the actors revealed their doubts, confusion, and willingness to be in the liminal between spaces. The disconnected narrative, bouncing from storytelling to acting exercises to confusion among the Wesleyan and Burden actors, created a nonsensical, awkward post-dramatic chaos that splintered my consciousness in ways that compelled me to pay more attention.

According to Pearl, one of the reasons the play’s adaptation to Zoom worked so well was that the team was already in the middle of owning it. “Since the play was already devised once, when we got to Zoom we could really continue to allow it to address the moment,” she said. The strategy Pearl led with was that the actors had to acknowledge the moment. “The breakdown of the Stella Burden company suddenly began to match the breakdown of the Wesleyan company,” she said. “The deep frustration the Stella Burden company was having—with not being able to move forward—matched that of the Wesleyan company. By the final scene where everything breaks down, I said, ‘Okay, we got the two stories to meld.’”

Early in the performance, audiences experience how the Wesleyan ensemble wrote their way into the disembodiment inherent in Zoom theatre. In the play, during an interview about the self-isolation practice Burden taught, the character Connie Torrey answers, “We are shattering the illusion of theatre and bodily co-presence by finding our inner audience and performer multitudes. We learn to project into an open void and know it will echo back.” This feels almost tongue-in-cheek, but those words were also heard as a plaint, a lament. I was conscious of the daring effort it took all the Wesleyan actors to project into that void as they reacted to their self-isolation and their characters reacted to the disappearance of their mentor.

I was conscious of the daring effort it took all the Wesleyan actors to project into that void as they reacted to their self-isolation and their characters reacted to the disappearance of their mentor.

Two College Productions Meet the Moment

A Zoom event akin to Wesleyan’s was Bard College’s April livestreamed production of Caryl Churchill’s Mad Forest, depicting events in Romania surrounding the fall of the Ceausescu dictatorship. One must ask why these Zoom performances landed squarely when so many other digital theatre performances fell flat. As has been suggested elsewhere, both productions possibly worked better than more traditionally narrative dramas because of the nature of the content itself. Plays that explore broken institutions, social unrest, and isolation may be uniquely suited to the Zoom platform with its fractured screen of boxes and its disruptive glitches, hiccups, and delays.

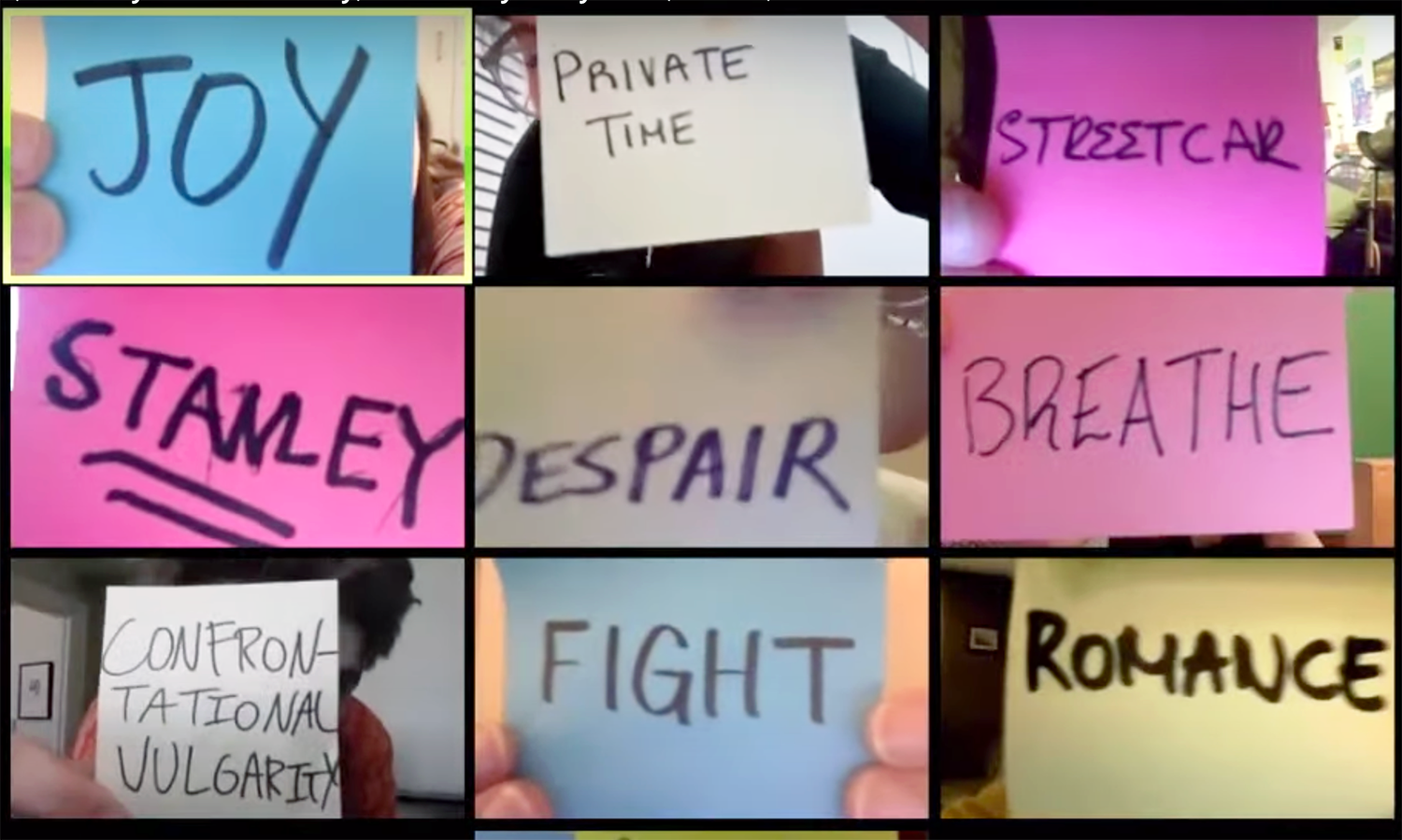

The difference between the two productions is that Bard brought on an additional New York designer to consult and help with the technological transition. All elements of the work, including scenery, choreography, and lighting, were assessed and adapted. Wesleyan’s production, on the other hand, was in the tradition of Jerzy Grotowski’s poor theatre. The students worked with the production and artistic teams to create as consistent a visual vocabulary as possible using homemade props and bedroom lighting, while coordinating their efforts across four time zones from Singapore and Macedonia to the west and east coasts of America.

The Wesleyan actors fiercely took audiences into the unknown, indeterminate present moment. We were left to ricochet with our own inner uncertainties in the face of the pandemic but also to taste joy and delight. The fractured Zoom screen met our fractured realities as the questions of absence, loss, and sorrow reverberated into our living rooms. The Stella Burden actors lost their teacher and the Wesleyan actors grieved the disconnection from one another in real time, as we the audience members watched, severed from much that was once familiar and comforting. The ensemble dedicated its performance to the text, to language itself, rather than to the idea of simply entertaining an audience or making a political statement. The play will be remembered as the first poetic Zoom theatre in the tradition of Richard Foreman, Peter Brook, and María Irene Fornés.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here