Men vs. Women on Broadway This Season

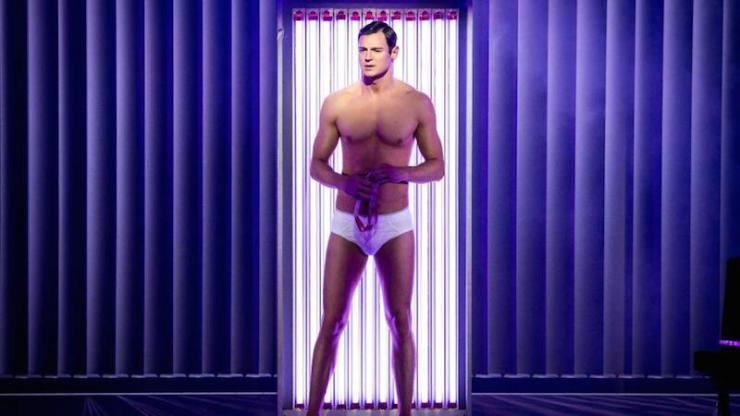

In a Broadway season just concluded that some say has been the most inclusive in memory, one musical tells the story of a young straight white man who kills women. American Psycho, starring Benjamin Walker as serial killer Patrick Bateman, opened just three days before Waitress, starring Jessie Mueller as Jenna, a waitress with a talent for making pies who is trying to break away from a loveless marriage. Waitress has been widely promoted as the first Broadway musical to feature an all-female creative team—director Diane Paulus, songwriter Sara Bareilles making her Broadway debut, choreographer Lorin Latarro, and book writer Jessie Nelson, which is based on the 2007 movie of the same name by Adrienne Shelly.

American Psycho and Waitress, which are performing two blocks away from one another, have several things in common. Both are stage adaptations (American Psycho was a 1991 novel by Bret Easton Ellis made into a 2000 movie starring Christian Bale). Both offer tuneful scores composed by well-known singer-songwriters. (American Psycho composer Duncan Sheik, who started out as a singer, is now best known for Spring Awakening.) Both are meant to be humorous.

But their types of humor are so at odds that the humor is part of what makes the two musicals so radically different from one another. The contrast between American Psycho and Waitress can be characterized as: edgy versus homey, snidely satirical versus warmly whimsical, and elusive versus clear. Would it be fair or accurate to sum these up as male versus female sensibility? Until recently, this question would have struck me as so reductive as to be absurd. Then late last month, after he won the Indiana primary, all but guaranteeing that he will be the Republican candidate for president, Donald Trump said at a press conference at Trump Tower: “Frankly, if Hillary Clinton were a man, I don’t think she’d get five percent of the vote. The only thing she’s got going is the woman’s card.” It’s jolting that a character in American Psycho refers to Donald Trump as Patrick Bateman’s hero.

Thinking about how stark the apparently gender-related differences in American Psycho and Waitress sparked a realization: Many of the Broadway shows that opened this season focus on what used to be called the “battle of the sexes,” a battle that evidently isn’t over.

Many of the Broadway shows that opened this season focus on what used to be called the ‘battle of the sexes,’ a battle that evidently isn’t over.

In the revival of The Color Purple, Cynthia Erivo portrays Celie, a woman who is belittled and abused by men for most of her life—first by a father who rapes her and takes away her children, and then by her violent and contemptuous husband to whom she’s given away at the age of fourteen. Such relentless Gothic misery instills in her a conviction that she is ugly and worthless, even when she has physically, and then even financially freed herself. This is why the audience responds so thunderously when Celie finally frees herself emotionally as well, in the rousing “I’m Here”—“I don’t need you to love me….I’m beautiful, yes I’m beautiful, and I’m here.”

Eclipsed shows women who are brutalized, abducted, and used as sex slaves by a rebel commander during the second Liberian Civil War at the turn of the millennium. Eclipsed ends more ambiguously than The Color Purple, but here too there is reason to cheer, thanks to the character of Rita Akosua Busia, a member of the Liberian Women Initiative for Peace; it is an amazing historical fact that women created a mass movement that helped end the fighting.

In Eclipsed, which was written by the actress Danai Gurira, abuse is shown from the women’s perspective, even more so than in The Color Purple. The men in Eclipsed aren’t even on stage; Eclipsed has an all-female cast. The abuse in Blackbird, a play written by David Harrower in 2005, is more ambiguous. In the revival on Broadway, Michelle Williams portrays Una, a twenty-seven-year-old woman who confronts Ray, a middle aged man played by Jeff Daniels who raped her fifteen years earlier, when she was twelve years old. Rape is the legal term, but we learn over the course of the play that, while inappropriate in every way (legally, morally, emotionally), they both wanted to have sex with one another. Una has tracked down Ray, who had served time in prison, changed his name, and now works as an executive in an office. Under the direction of Joe Mantello, the Broadway production ramps the theatrics. They scream at one another, get physical, even completely empty a big garbage can full of trash. It all struck me as nothing more than a star-driven exercise in showy acting and goosed-up dramatic tension. Others have disagreed, finding it powerful, but is it offensive to ask whether this story was written and directed with a male sensibility—the point being powerful dramatics, rather than an inquiry into the complexity of human nature? We may have a partial answer in that the Pulitzer winning play by Paula Vogel, How I Learned To Drive, which is on much the same subject, has none of the pyrotechnics, and much more insight.

Something similar to Blackbird was going on with the Fall revival on Broadway of Sam Shepard’s Fool for Love, in which Nina Arianda and Sam Rockwell played two Westerners caught in a violent push-pull relationship. It’s easier to make the case that the interaction between the man and the woman in this play is more equal—mostly, mutually abusive. But, this production directed by Daniel Aukin was the first in a Manhattan Theater Club season that had been loudly criticized as lacking in diversity. Rather than seeing the revival the way some did—as a metaphor for the desiccated American West or for the downside of love—it seemed to me an impressive acting exercise and the theatrical equivalent of a low-budget action flick.

It’s interesting to contrast Fool for Love with Thérèse Raquin, the Roundabout’s adaptation of Emile Zola’s tale of adultery and murder starring Keira Knightley making her Broadway debut. The story is hardly subtle, but it felt like a more realistic and nuanced portrayal of a mutually destructive male-female relationship (at least to me—critical reception was evenly split, half loving, half loathing the production).

None of these shows paint an encouraging picture of the relationship between men and women. There are other shows this season that offer a more positive view. The play The Gin Game and the musical She Loves Me are largely benign, or at least are meant to be taken that way. There are several uncomfortable threads in the Harnick and Bock musical, written in 1963, about two bickering co-workers who are Miss Lonelyhearts pen pals without knowing it. At one point, the man George finds out that his hated co-worker Amalia is his secret love, and not only does he keep the information from Amalia, but uses it to tease her in a nearly cruel way. In their next musical, Fiddler on the Roof, Harnick and Bock have a thought-provoking take on love and the sexes: Tevye’s daughters get their way in whom they choose to marry, against their father’s wishes, but in the process help destroy tradition (or, at least, embody the times in which tradition is being destroyed).

What does it say that some of the very shows in the 2015-2016 Broadway season that are most often cited as creating the most inclusive season in memory are the ones that seem to offer the most hopeful and healthy relationships between men and women?

What does it say that some of the very shows in the 2015-2016 Broadway season that are most often cited as creating the most inclusive season in memory are the ones that seem to offer the most hopeful and healthy relationships between men and women?

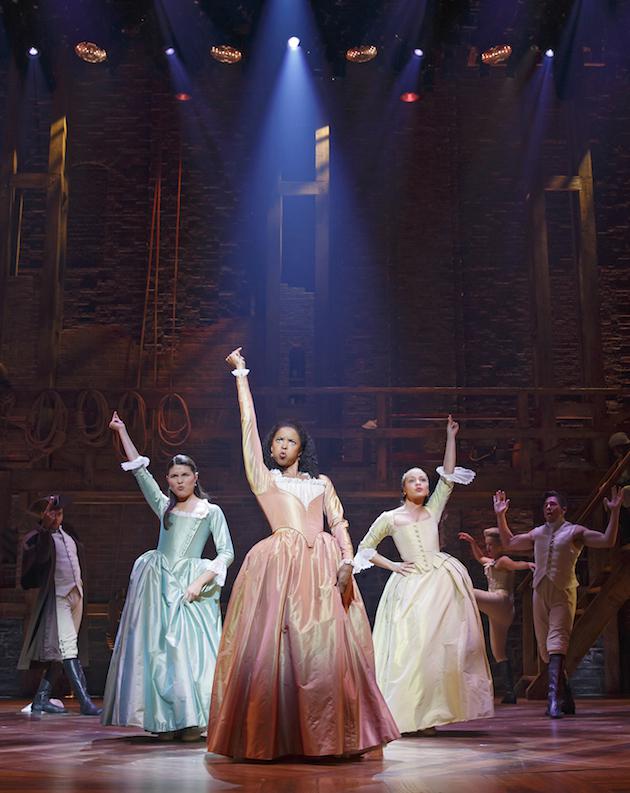

On Your Feet suggests an equal partnership between Gloria and Emilio Estefan. Alexander Hamilton cheated on his wife, causing the first political sex scandal in American history. Yet Hamilton the musical offers at times a dose of feminism as strong as those in the female-centric shows this season, Waitress and Eclipsed. In the song, “The Schuyler Sisters,” the three women sing: “We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal.”

And then Angelica alone adds:

“And when I meet Thomas Jefferson

I’m a compel him to include women in the sequel!”

Hamilton doesn’t end with Alexander Hamilton’s death. It ends with his widow Eliza. Earlier, the last thing Alexander Hamilton sings before the deadly duel, is from the actual last letter that Alexander Hamilton wrote to Eliza Hamilton:

Best of Wives and Best of Women

***

Jonathan Mandell’s newcrit piece usually appears the first Thursday of each month. See his previous pieces here.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

First, thanks for liking my article!

I was careful in how I described Hamilton for just the reasons you state. I pointed out that Alexander Hamilton cheated on his wife. I said Hamilton "offers at times a dose of feminism..." and then backed that up with two concrete examples. I didn't call the show "feminist." I said that it "at times" offered "a dose" of feminism. I don't see how anybody can read the lyrics Angelica Schuyler makes about including women in the sequel as anything but Lin-Manuel Miranda's deliberate -- and probably ahistorical -- injection of a modern feminist attitude

I'm not sure what you are suggesting Miranda could have done to make Hamilton more acceptable to you -- throw in nine more female characters for gender balance? Not write a musical about Hamilton at all? Please remember that the musical is based on a specific book by a historian. Kindly blame history (or at least that historian) for the focus on men. We to this day refer to the people who founded the United States as the Founding Fathers. For all that, Miranda has rescued the Schuyler sisters from obscurity.