“The most gorgeous group of f*ck ups” in Airline Highway at Steppenwolf

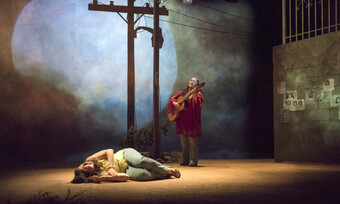

“34.99 and up, low weekly rates, vacancies. OPEN.” read the signs on the Hummingbird Motel, the setting for Lisa D’Amour’s Airline Highway, directed by Joe Mantello and running at Steppenwolf Theatre Company (December 4-February 14) with a Broadway transfer planned for Spring 2015. A broken down sedan rests on cinder blocks in its trash-littered parking lot. Rusted gutters hang precariously from its balconies in Scott Pask’s detail-oriented, realistic set. It is a bleak place, a run-down two-story motel that has clearly seen better days. Yet there are touches of hominess—a plant hangs from an awning, its flash of green a demonstration of how life can thrive in this desolate landscape. Bras and panties dangle on the balcony to dry. At the top of the show, handyman Terry (Tim Edward Rhoze) sits on the steps, watching casually as the audience filters into Steppenwolf’s downstairs theatre.

Airline Highway is about community. The story focuses on a funeral for veteran burlesque dancer and mama hen Miss Ruby (Judith Roberts), thrown by her “little chicks” while she is still alive so she can attend it in the parking lot of the Hummingbird Motel, where they are long-term residents. The Hummingbird community is a family of choice, a band of hustlers, artists, and sex workers living on the fringes of New Orleans’ tourist economy—they are, as Miss Ruby puts it, “The most gorgeous group of fuck-ups I have ever seen.”

The Hummingbird community is a family of choice, a band of hustlers, artists, and sex workers living on the fringes of New Orleans’ tourist economy—they are, as Miss Ruby puts it, 'The most gorgeous group of fuck-ups I have ever seen.'

The funeral event, in all its festive fabulousness, is primarily an excuse for the audience to get to know the Hummingbird’s richly textured characters, including homeless stripper Krista (Caroline Neff), list-making prostitute Tanya (Kate Buddeke), upbeat transsexual Sissy Na Na (K Todd Freeman), bicycle riding poet Francis (Gordon Joseph Weiss), motel manager Wayne (Scott Jaeck), and the aforementioned handyman Terry. These characters may not all live long-term at the Hummingbird—a motel designed for short term stays in the transient space of the highway to the New Orleans airport—but they are all permanent members of its community.

Bait Boy (Stephen Louis Grush) has escaped from the Hummingbird into a more conventional life in suburban Atlanta. He returns for Miss Ruby’s funeral in a preppie pink collared shirt, bearing a tray of sandwiches from Whole Foods, with his teenage stepdaughter Zoe (Carolyn Braver) in tow. Zoe is working on a sociology project; she wants to interview members of the Hummingbird’s “subculture” for her honors paper. Her approach is represented as naïve—she does not know just how little she can understand of this world and the people in it from an afternoon’s visit. But she is us—the Steppenwolf audience of mostly white, middle aged, and middle to upper middle class looking theatre patrons sitting in our comfortable seats, sipping our drinks from the lobby bar. Zoe is a well intentioned tourist-as-voyeur, peering in on the exotic drag queens, artists, strippers, and hookers building lives on the fringes. She stands awkwardly by, trying to engage residents in interviews, as the ensemble—the family—decks out the hotel with streamers, feather boas, fans, Christmas lights, and a disco ball to transform the drab parking lot into a space worthy of the celebration of Miss Ruby’s life.

“How did you come to be here?” Zoe asks. Wayne (Scott Jaeck) launches into a very long story, beginning with his grandfather and rambling through generations of family history. It is not until he is deep into the telling that it becomes clear that he is trying to explain how his white family fell from the middle class and landed here. The play argues that it does not really matter exactly how these people came to be here—it does not ever explicitly answer that question for any of the characters—what matters is the lives they live with each other. In their teasing, squabbling, and nurturing, they are clearly a family.

Zoe falls in love with this community, declaring it more real—more authentic—than her pressure cooker suburban high school existence. She bemoans that she can see her whole life set up before her as a future “perfect suburban wife.” “Don’t call me little girl, don’t call me little girl; I won’t give up until I’ve seen the whole wide world,” she sings, joining her voice into a blues song the ensemble improvises as part of the funeral festivities. She does not recognize that, despite the exotic “authenticity” of the party, the mainstream life in which she feels trapped is likely to be less ridden with fewer obstacles and less pain than the lives of the permanent members of this community.

At intermission, I overhear a middle aged white couple who seem to be on a first date talk about having been to New Orleans. The well-dressed man seems to be trying to impress his date—a woman far younger and prettier than he—regaling her with tales of authentic New Orleans debauchery at Jazz Fest. He doesn’t seem to realize he’s illustrating Director of New Play Development Aaron Carter’s program note, entitled “Authentic Dirty Sh*t,” highlighting how we—the audience with our “mainstream ordered lives” are but tourists “seeking authentic dirty shit… experiences supposedly unmediated by those same societal expectations we chafe against.” The New Orleans tourist experience, Carter posits, revolves around giving mainstream middle class people encounters with their wild side that feel more “real” or more “authentic” than their more comfortable and ordinary day-to-day lives. This dynamic plays out in both Zoe’s story and the story I overhear at intermission. The characters in the play do not have the luxury of this escape—their day-to-day lives are actually, authentically enmeshed with the “wild side” of New Orleans and they bear the scars to prove it.

The New Orleans tourist experience, Carter posits, revolves around giving mainstream middle class people encounters with their wild side that feel more 'real' or more 'authentic' than their more comfortable and ordinary day-to-day lives.

D’Amour focuses the play not on their pain, but on their joy and celebration of a life fully lived, using the “living funeral” as a landscape to highlight her nuanced characters and their complex relationships. Indeed, the funeral doesn’t change much in the character’s lives—the next day is much the same as the last, and each day brings little hope for positive change. But in the parking lot of the Hummingbird, this ragtag pack of outcasts has created a space in which they can take care of each other, and together, they will make it through.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here