In the first case, individual stories and/or the global situation of refugees becomes the material for a theatrical work that aims to raise awareness. Often these works are made by professional theatre artists who are not refugees themselves. This is the most compromising type of refugee theatre because it does not meet the basic democratic principle of “nothing about us without us.” It is true that even in this type of refugee theatre, there are very important examples, like The Jungle by Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson or The Claim by Tim Cowbury and Mark Maughan.

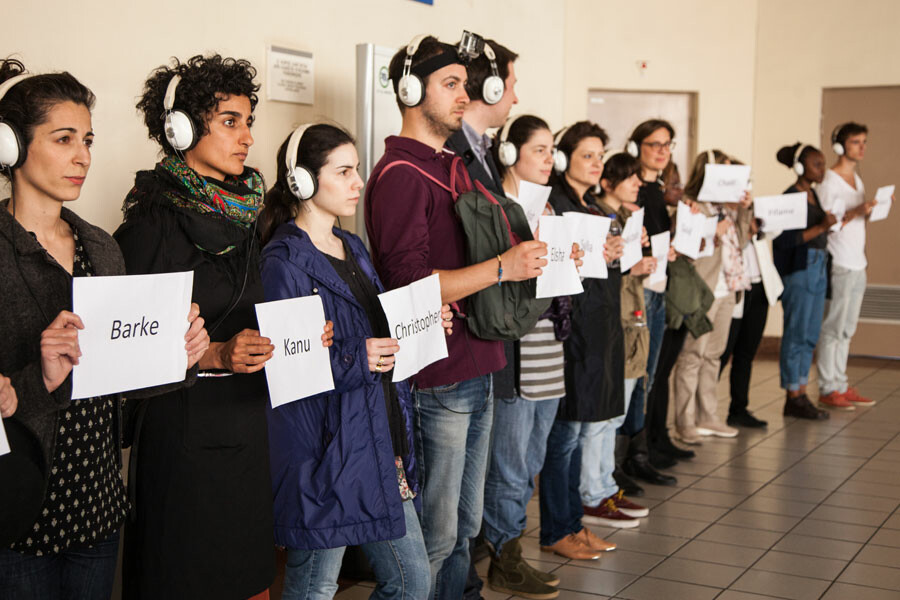

In the second case, people with migration experience become participants in theatrical works themselves. This is already better, but there can also be a range of different power dynamics: sometimes, this type of show may have non-refugees writing these works and exploiting refugees with their narrative while other times it could actually feature refugees taking full control over their story and how it is being told.

In the third case, refugee theatre aims to help people with refugee experiences, whether it is with creative self-expression; the lease of tension and frustration through storytelling; therapeutic processing of trauma; or reflective feedback sessions that allow them to replay certain situations and draw conclusions from them, thereby leading to personal growth. This is often the method used in helping refugees integrate and assimilate. The ideal situation, of course, is when all three of these are combined in one work that is about, with, and for refugees, thus having people with refugee experience directly involved in creating and producing work about themselves, raising awareness about migration situations, and growing through the reproduction and reflection of their experiences.

I believe that the role of art, especially performative art, is not simply to comment on catastrophe or dramatic events but to participate directly in the process of change. By raising awareness, becoming a forum for discussion of politics, broadcasting marginalized experiences, and amplifying the voices of those who are not being listened to, theatre affects the way society is structured. Refugee theatre received particular attention after the migrant crisis in the mid-2010s, but the connection between theatre and refugees goes back much further.

From the very beginning of their journey, refugees are forced to dramatize their lives, especially when they find themselves in a situation of bureaucratic mazes. Much depends on a refugee’s ability to convincingly construct a “sympathetic” self-narrative in the face of the migration administrations in the countries they arrive in.

Immediately after the end of World War II in 1945, the largest refugee camp in Denmark was set up in Oksbøl city, with some thirty-five thousand German civilians living there. In this camp, there was the Theater-Oxbøl with eight hundred seats. Recently FLUGT — Refugee Museum of Denmark launched an audio performance on the site where the camp used to be. This performance was impactful, as it allowed the audience to experience the atmosphere of that time and to be transported to the Theater-Oxbøl.

Another example is Dwight Conquergood, who in his 1988 article “Health Theatre in a Hmong Refugee Camp: Performance, Communication, and Culture,” writes about how rich in performative events Ban Vinai Camp in Thailand was for highlanders. He writes: “Camp Ban Vinai may lack many things—water, housing, sewage disposal system—but not performance. The camp is an embarrassment of riches in terms of cultural performance. No matter where you go in the camp, at almost any hour of the day or night, you can simultaneously hear two or three performances.” These performances ranged from simple storytelling to folk singing to ritual performances for the dead that incorporated drumming, dancing, stylized lamentation and ritual chanting, manipulation of funerary artifacts, incense, fire, and animal sacrifice.

Interestingly, in this article the author notes the large presence of cultural performances in refugee camps in general: in addition to Ban Vinai, he visited eleven other camps in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Nigeria. He attributes this to the fact that in refugee camps, people fall into a liminal state in which a significant part of their identity is lost and a new one has not yet been formed. This—and plenty of free time—allows refugees to experiment with their identities and strategies of adaptation, survival, and resistance. Conquergood writes: “Through its reflexive capacities, performance enables people to take stock of their situation and through this self-knowledge to cope better. There are good reasons why in the crucible of refugee crisis, performative behaviors intensify.”

Many researchers at the intersection of performance and migration have noted that the refugee experience is highly performative, even without the inclusion of the refugee in participatory theatrical practices. Alison Jeffers writes about this at length in the first chapter of Refugees, Theatre and Crisis: Performing Global Identities, where she describes what she calls “bureaucratic performance.” From the very beginning of their journey, refugees are forced to dramatize their lives, especially when they find themselves in a situation of bureaucratic mazes. Much depends on a refugee’s ability to convincingly construct a “sympathetic” self-narrative in the face of the migration administrations in the countries they arrive in.

There are a huge number of cases where refugees are denied residency permits and deported simply because their story is not believed. This is especially common for queer refugees seeking asylum, who are often discriminated against on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. Bureaucrats in many European countries often use legally gray areas to deny subsidies or the right to stay based on a lack of trust in a refugee’s story. Even after being placed in a refugee camp or receiving documents and beginning the assimilation process into their new country, the migrant’s performance of their personal identity does not cease.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you for sharing your insight, experience, and best practices. My company RealTime Interventions will take this to heart as we begin our next project, with Ukrainian humanitarian parolees.

From 2017-2020, we worked with a group of former female Afghan refugees, in conjunction with refugee resettlement in Pittsburgh, to create a show to forward the group's stated desire to start the first Afghan food business in Pittsburgh. Supported by our city's wonderful Office for Public Art, we developed the play with the guidance of the Afghans at every step. While they preferred not to perform, they chose the women that would tell their own stories onstage. The script was written in response to the question, What do you want Americans to know-- about you, about your country? We did rounds of back-and-forth during the writing to make sure they approved of every line.

You may not be surprised to learn that overall they had little interest in retelling their oppression, refugee, and trauma experiences. Mostly they wanted to share the physical beauty of their provinces, their food, their culture, how they celebrate important moments (the New Year, birth, death, Ramadan.) And this was extraordinarily moving to audiences. Rehearsal of trauma is simply not required for great theater. Each of those women is infinitely more interesting than just being "a refugee"; every person has so much more to tell than what happened on the worst day of their life. Moreover, it was their show to co-create, using their stories, and our pay structure reflects that-- every time we do the show, we pay them royalties.

Building the food business was not an afterthought. For new immigrants who've had to leave everything behind, financial survival is top of mind. In the show, the women cooked while actors told their stories and their children served the food to the audience. This allowed them to do informal "market research" on what dishes would do best in their business, and helped us provide childcare while the women participated. At the same time, the shows gave them catering experience, and during the creation process we partnered with over 20 orgs and food businesses in town to get them training in commercial kitchens, ServSafe certification, mentorship from restaurant owners, LLC paperwork, insurance.. We raised $3k in seed money for their business during the run, and long story short (long?), they emerged with the first Afghan food business in Pittsburgh, Zafaron Afghan Cuisine, co-operatively owned and operated by them.

Art can create tangible improvements in people's lives. It can create empathy and cultural awareness without re-traumatization. Thanks again for your article-- based on the length of this comment, maybe I should write my own 😬 [For more you can visit http://realtimeinterventions…]