Part Two

Dialogue in the Age of Industrial Storytelling (Or, A Defense of the Theater)

This essay follows a previous one, entitled Dialogue and the Age of Industrial Storytelling (Or, A Defense of the Theater). It is less a continuation of its predecessor than a response to it. Whereas Part One articulated the notion of industrial storytelling as critical to an understanding of contemporary dramaturgy, Part Two offers a critique of the industrial dramaturgical model.

The finest achievement of human society and its rarest pleasure is Conversation.—Jacques Barzun

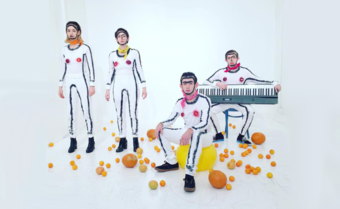

Photo by London, Hollywood.

1

In Pixar’s Finding Nemo, Marlin, the father clownfish (played by Albert Brooks), loses Coral, his beloved wife—and mother of his son-to-be, Nemo—to a marauding barracuda. This loss comes almost at the outset of the film, a loss that defines Marlin’s character and the through line of his story. When Nemo gets scooped up by scuba divers later in the first act, it is Marlin’s journey to find him that gives the film its story and title.

The writer’s task was not easy. Marlin’s psychologically thoroughgoing motivation—both his terror over the prospect of losing the only child Coral gave him, as well his desperate need to recover that son once Nemo is lost—had to be established swiftly. We had to be made privy to the power and beauty of the bond that Marlin shares with his wife, a love and comfort that he loses when he loses her. The writer has one scene to do it, and the scene the writer chose to accomplish the job is simple and elegant. In it, Marlin is showing his wife the “house” he has found for them. As he assesses his wife’s reaction to seeing it, the dialogue begins:

MARLIN

Wow.

CORAL

Mmm-hmm.

MARLIN

Wow.

CORAL

Yes, Marlin. No, I see it. It's beautiful.

MARLIN

So, Coral, when you said you wanted an ocean view, you didn't think that we we're gonna get the whole ocean, did you? Huh? [sighs] Oh yeah. A fish can breath out here. Did your man deliver or did he deliver?

CORAL

My man delivered.

MARLIN

And it wasn't so easy.

CORAL

Because a lot of other clownfish had their eyes on this place.

MARLIN

You better believe they did—every single one of them.

CORAL

Mm-hmm. You did good. And the neighborhood is awesome.

MARLIN

So, you do like it, don't you?

CORAL

No, no. I do, I do. I really do like it. But Marlin, I know that the drop off is desirable with the great schools and the amazing view and all, but do we really need so much space?

MARLIN

Coral, honey, these are our kids we're talking about. They deserve the best. Look, look, look. They'll wake up, poke their little heads out and they'll see a whale! See, right by their bedroom window.

CORAL

Shhh, you're gonna wake the kids.

The operational conceit of the scene is to establish the identity of the viewer with these fish subjects. They have families; they are families. They think about their neighborhoods and their schools and keeping up with the Joneses. They want a good view. They argue about what to name their kids. They joke about their first date.

This process of identification proceeds along preemptive lines, for there is no time in such a setup for the slow reveal, for a narrative movement that foregrounds difference, then moves gently toward a dawning recognition of similarity. Indeed, the modern animated feature film is an accomplishment at the very limits of human achievement, comparable in its own way to the sort of pinnacle that the creation of the pyramids must have represented to the ancient world, and with such Pantagruelian investment of human and financial resources, there isn’t time to risk the loss of the viewer. Identity must be conveyed with force and immediacy. Brought home in line after line of dialogue, the deft, surprising execution is only a mask for the startling tautology at work at a deeper level:

CORAL

Just think that in a couple of days, we're gonna be parents!

MARLIN

Yeah. What if they don't like me?

CORAL

Marlin.

MARLIN

No, really.

CORAL

There's over 400 eggs. Odds are, one of them is bound to like you.

MARLIN

You remember how we met?

CORAL

Well, I try not to.

MARLIN

Well, I remember. "Excuse me, miss, can you check and see if I have a hook in my lip?"

The procedure defines a logic that will obtain in various forms through the course of the film, a logic that defines the very ontology of content itself: He is like you. She is like you. They are like you. That’s why you love them. For after all is said and done, the deepest truth, the most worthy meaning, is that we are all—each and every one of us—the same.

Growing capital has become our collective telos, the ultimate purpose of our body spiritual and politic; spiritual, for make no mistake, our capitalist dreams of abundance are no less the result of our desire for immortality than our erstwhile myths of paradise were. Capital must grow.

2

What are the rules of this sameness?

They are familiar to us all in the primetime smile of advertising, the cornered grief of the victim, the triumphant defeat of pain (even death) through various forms of ecstatic accumulation. And these are just a few of the familiar tropes. Indeed, to be sentient in the late-capitalist moment is to be bombarded with an unceasing litany of clichés about comportment and aspiration and the ultimate substance and meaning of the inner life, bromides and formulas comprising an inventory of the human as articulated by a late-capitalist majority. Our late-capitalist civilization is committed to the ascendency of the moral and experiential middle of human life, to life lived in the bulge of the bell curve. For when we are in the middle we are more alike. And it is that much easier to know and service our collective needs and desires.

Capital must grow.

This late-capitalist civilization—what Debord termed the Spectacle—maintains its grip through concussive redundancy, the messages of sameness, of aspirational normalcy, repeated and recycled and repurposed ad nauseum like an unceasing cognitive behavioral loop playing on the headphones of the cultural consciousness. And when this redundancy fails—that is, when messy human abundance cannot be vanquished with formulas—the pharmacological experiment intervenes, this unprecedented project of rechanneling human neural chemistry to hew, like an unruly river tamed, to the more reasonable demands of commerce. (Even the most recondite recesses of our human nature have undergone their systematization, as in the wholesale colonization of the erotic by modern pornographic tropes enshrining the sale of the self as the most enduring of human intimacies.)

Capital must grow.

Such is our economic covenant. (Capital, or a sublime abstraction of our human needs and aspirations, an abstraction we have all but ceased to see as such, which lack of recognition is the likely root cause of all the financial ills that haunt us now.) Growing capital has become our collective telos, the ultimate purpose of our body spiritual and politic; spiritual, for make no mistake, our capitalist dreams of abundance are no less the result of our desire for immortality than our erstwhile myths of paradise were.

Capital must grow.

The preservation of this dream of completion, the securing of the means by which it can be fulfilled, this is our new, our only holy devotion. And what can give us the security, the predictive power to grow our capital? Information. What we love. What we hate. What we need. What we want. What we watch. What we click…

In short, the enumerations that indicate what we will buy.

Are we moved by an identification that is the result of the traits we recognize in the characters before us—on screen, on stage—or by something beyond the enumerable?

3

The one thing almost every professional practitioner of the theater knows is that there’s no money in it. It can seem like a daily miracle that the form survives at all, a poor passion hobbling along, its antiquatedness catching uncomfortably in the quicksilver channels of industrial exploitation, like decaying autumn leaves clogging up the drain pipes. The theater makes demands on reality. Notably those of space and presence. It needs a room, or something like it. It requires people to be there. It forces proximity and communication. It necessitates (and thrives on) living dialogue. In other words, it is an art form scaled to the human, and stubbornly so, its structural rigidity and technical obsolescence a large part of why the form resists monetization. It cannot be copied and sold. It only happens here and now. It does not exist to be pulled out at the consumer’s whim or discretion. In short, the theater does not breed the sorts of simulacra that could help it compete on the endless screens of contemporary consciousness. Defined by quiddity, the theater admits no virtuality. Walter Benjamin might have been pleased to know, some eighty years after his seminal essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, that the theater would remain an art form—perhaps the only one—immune to the denaturing of mechanical reproduction.

4

It requires a room. People in that room. It is limited by its need for proximity and presence. These are its weaknesses, as an economic form. But they are strengths in human terms.

The theater’s human scale defines why it will always be central, indeed essential, to our lives, to our societies, irrespective of our changing covenants. The subversive truth of the form today is that, in a world increasingly populated with likenesses of relationship, the theater at root is still about relationship. Fundamentally, the relationship between an embodied actor and an embodied audience.

The body. Or another way of figuring the fundamentally human scale of the theater. A comprehensive analysis of the relationship between a theatrical audience and the theatrical actor falls beyond the pale of our immediate concern here. But for our purposes, suffice it to say: we speak so often of a character as s/he is written, but is this not a failure of our understanding of what really transpires in the theatrical moment? Isn’t the bond one that passes or circumvents analysis? Which isn’t to say we cannot understand it. But the terms of that conversation would not be dramaturgical. Indeed, by sounding out our own relationship to the living actor on stage, we begin to understand a different register of relationship. Not enumeration of traits and qualities, but something more ineffable. More charnel. More immediate.

Consider:

Not the description of the taste of a ripe mango. It’s orange-yellow succulence, say. Or the biting sweetness that can linger in the mouth like a perfect fifth echoing in a cello’s lower bouts. No. Not this. Not anything like it. Indeed, nothing that can be said at all. But rather:

The taste itself.

5

Derrida has posed the crux of the matter with characteristic elegance:

Does my heart move because I love someone… or because I love the way that someone is?

It could well be the central question of all acting technique, of all narrative dramaturgy. Are we moved by an identification that is the result of the traits we recognize in the characters before us—on screen, on stage—or by something beyond the enumerable? In other words: Do I feel the loss of Coral because of the what she is—a nurturing suburban mother, say, or a supportive and loving wife—or do I feel her loss for some other more ineffable, more mysterious reason, something that points to who she is?

Of course, in the case of Finding Nemo, it can only be the former. The aesthetic field has been ceded entirely to a dramaturgy of enumeration. This is dramaturgy of the multitude, a structural appeal to the commonest denominator. Traits are accumulated, catalogued, put to use. Characters are defined by the qualities they exemplify. Likeable qualities must dominate. Types move the story forward. Counter-types oppose. Quirky types offer segues and interludes and entertain with local color. Each type must be recognizable, and—this is key—all recognition must be capable of articulation. (For executives and marketing departments and advertisers will need to decoct and tag and reformulate into even simpler terms for the sake of their unceasing appeals to the planetary pocketbook.) When the pitches have been delivered, the scripts written and shot, the up-fronts completed and deals closed, that is, when all has been said and sifted and produced, the summary wisdom of the industrial process can be distilled into a single sentence, the ubiquitous sine que non of contemporary narrative, the creedal conclusion of every poetics of the what:

The characters must be likable.

Thus has the process of sympathy been formulized for the purpose of commerce. Thus has our expectation been formed to the demands of supply. And thus does the industry undertake the education our capacity to feel.

6

To be a narrative writer today—screenwriter, playwright, novelist—is to be confronted with this dominion of the what. It is also to be confronted and confounded with the need for something called change. In which a character’s new (preferable) traits organically replace older (less preferable) ones. What is lost in this way of seeing the development of character is something fundamental, something true about the insolubility of human life.

Human character is not simply the sum of parts that can be reformulated to produce a different, and more desirable, alloy.

At the heart of human identity is a mystery that stands in as a figure of the larger mystery of life. And the entrammeling of the mind by this endless conundrum represents the paradigmatic dramatic form. In Kierkegaard’s words:

Some day the circumstances of your life may tighten upon you the screws of its rack and compel you to come out with what really dwells in you, may begin the sharper inquisition of the rack which cannot be beguiled by nonsense and witticisms.

The inquisition of life and self, unbeguiled by the witty nonsense of likeability, and where every poetics of the who must truly begin. For authenticity—like the eternal mystery of identity—can never be reduced to a formula.

7

Is Finding Nemo—however much it may hew to the standards and practices and procedures of the human as we have come to know them through the modality of the marketplace—any less a triumph for all of that?

Perhaps not. Indeed, industrial storytelling is often at its best in content targeted for children. (Get ‘em while they’re young.) Yet, we cannot fail to recognize:

A dramaturgy of the multitude—a poetics of the what—is of profound consequence to the texture of our lives. Percy Shelley famously wrote that poets and philosophers were the unacknowledged legislators of mankind. So it is today. For our stories convey to us the spectrum of human possibility, the conceivable dispensations of our human freedom. When these come to be figured and encompassed by tropes that serve the order of the industrial—redemption at all costs; sameness as a matter of ontogeny; the fiction that identity is an aspirational ladder—how could there not be a correlate impoverishment of the human itself?

8

It is not that film cannot display a more authentic, less cloying dramaturgy. To be sure, where the multitude is of less concern, there is more tolerance for the question, less irritable reaching after answers. Ultimately, though, the matter may have more to do with form than we realize, the impoverishment of the theater’s means offering the only truly necessary condition of authenticity: a foregrounding of the human.

This essay’s precursor made reference twice to Pinter, paradigmatic in his relationship to the spoken word as a vehicle to a deeper, more mysterious register of creative experience, as a portal to authenticity. Perhaps it is no coincidence that he was an actor. For he seems to understand implicitly the way dialogue defines presence—a character’s presence, yes, but which we must see as the metonymic complement of human presence itself:

… my job is not to impose upon them [the characters], not to subject them to a false articulation, by which I mean forcing a character to speak where he could not speak, making him speak in a way he could not speak, or making him speak of what he could never speak. The relationship between author and characters should be a highly respectful one…

He could just as well be describing our respect for the speaking of those arrayed before us on a stage. Our respect for the dialogue they will begin. And which—with any luck—will engender a dialogue in us as well.

Isn’t this what we’re all waiting for in the darkness before the lights come up?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Ayad, I echo Michael's response about this piece as a terrific piece of complex criticism in a tradition of greats. I'm also thinking of it in a slightly different way (given what I was watching last night). People characterized Bill Clinton's speech last night as poetic-covered policy, wonkery made personal. I find I have a similar response to your post. In your piece it's the policy *of* poetics, taking poetics apart, dissecting the means and mode of making theater as a call for the form to embrace its most complex and presence-filled reality (at least as I read it, admittedly quickly this morning). This is dramaturgical wonkery (if that can even be a thing) at its most inspiring. There's lots more to connect the "fiction that identity is an aspirational ladder" you mention and both political conventions, but I'll just leave it at dramaturgical wonkery.

Ayad, this is like reading Mamet essays from the 80's (the good ones, before he was a political blowhard) crossed with Chomsky interviews (where you have to work, but can make sense of it, as opposed to some of his essays which can demand an attention that obscures his oh so solid points) blended with some Harold Clurman writing about Brecht. All that name-checking to say, wow. heady stuff, with real heart. Thank you.