Pulp Ibsen

Chekhov’s Gunmen

For years, genre storytelling for the stage has been discounted and pushed to the wayside. It’s often deemed unable to compete with the “serious” storytelling capabilities of Realism. This series presents an overview of the rich history of genre theatre, which is broken down by category, and outlines the possibilities for Fantasy within the dramatic arts.

Howdy partners! Never one for shying away from ambition, this installment of Pulp Ibsen is dedicated to Western theatre! No, not Western theatre as determined by the definitions of Western civilization developed during the Peloponnesian War. That would be too easy. Instead, I’d like to opt for something a bit…wilder.

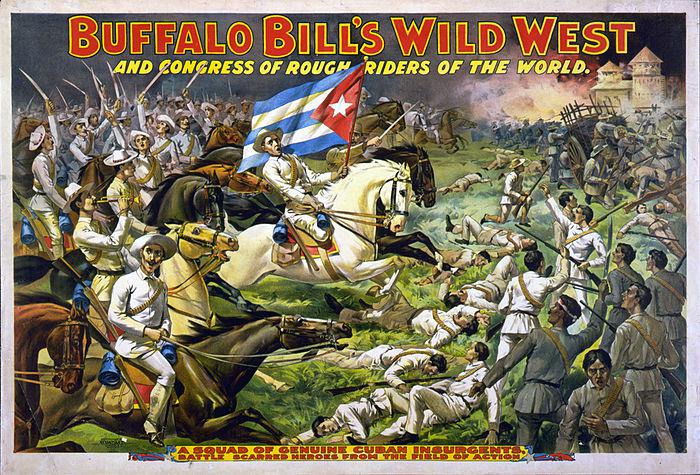

The second entry in this series highlighted the Fantasy genre in theatre, whose legendary chivalric knights formed the backbones of the desperados and lone gunmen of the Wild West. Like the knights of Arthurian legend, nomadic gunfighters of the Spaghetti Western wandered on horseback to dispatch villains, and were bound to no fixed rule of law but their own honor. However, daily life on the American frontier was certainly not as tall as the tales cemented in our minds. Many of these myths were consecrated for the first time on stage thanks to the classic travelling vaudevillian Wild West shows in America and abroad. In particular, the most famous show was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World!

Buffalo Bill’s reputation was first cemented in theatre, long before he started his own show. Born William Frederick Cody, “Buffalo Bill” (a nickname he earned while hunting buffalo for pay to feed railroad workers) earned fame as an army scout and hunting trip leader. When author Ned Buntline’s dime novel Buffalo Bill, the King of Border Men (1869) was turned into a theatrical production, his fame spread throughout the east, culminating in a touring production with Cody starring as himself, quickly thereafter starting up his own theatrical troop.

The earliest predecessor to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show belongs to mid-sixteenth century France, in which fifty indigenous Brazilians were brought to Rouen to replicate their village. Similarly, Bill Cody’s Wild West show, which formed in 1883, brought the imagery of the West to the rest of America. His shows contained various types of Western spectacle, including sharpshooting by Annie Oakley (who was the inspiration for Irving Berlin’s popular Broadway show Annie Get your Gun), hunts, animal races, historical reenactments, and Rough Rider parades (featuring future President Theodore Roosevelt). These performances often lasted up to four hours and attracted thousands of people. While there were many competitors in the Wild West show arena at the time, Buffalo Bill was its undisputed champion for almost thirty years. Due to poor management and stiff competition, however, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show closed in 1913 and many said the era of the Wild West was officially over.

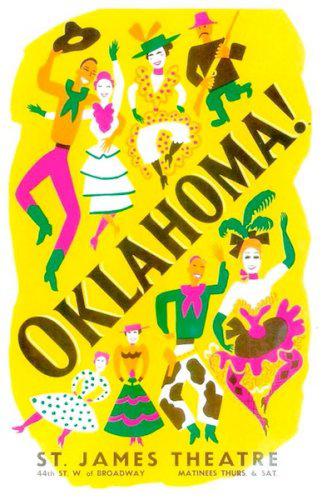

Yet, the theatre of the Wild West was not limited to razzle-dazzle variety shows. In the late nineteenth century, many great stage plays were set against the backdrop of the newly acquired Western territories. For instance, August Thomas’ Arizona (1899), which takes place in Arizona Territory before the Spanish American War of 1898, and tells a love story between a young cavalryman and a rancher's daughter, as well as, Edward Milton Royle’s The Squaw Man (1905), an epic Romance set in the wilderness of Montana. The Squaw Man was a massive critical success in its day, spawning four Broadway revivals, a musical, and three films, which were all directed by Cecil B. De Mille. Plays like Arizona and The Squaw Man were met with great enthusiasm upon their premieres; however, their success pales in comparison to the spiritual successor of the greatly exaggerated Wild West shows—the Broadway Musical.

It was on New York stages during the twentieth century that the myths of the West found new life. One of the more successful musicals dealing with the West was the Pulitzer Prize nominated folk musical Green Grow the Lilacs by Lynn Riggs; the cast for the original production included a then unknown Lee Strasberg. While this play is largely forgotten in its original form today, it went on to serve as the basis for one of the most acclaimed and popular American Musicals ever written: Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! (1943).

It’s true that the Wild West has largely disappeared, although some still say it can be found by looking hard enough at the deep pockets of America. Some of these pockets are nestled in the land, while others are buried in our national character.

As the twentieth century progressed, theorists in film genre studies argued that “Westerns” do not have to take place in the literal west, or even in the nineteenth century. These ideas can be applied to the work of Sam Shepard, who wrote several plays explicitly about cowboys, including The Tooth of Crime, a Sci-fi rock musical that intersects with my last entry on Science fiction. Shepard has also authored many plays that function as contemporary Westerns, while depicting loners, lawlessness, and personal codes of honor in the contemporary American West.

There have also been a few playwrights across the pond who tried their hands at giving the Wild West a theatrical update, including Jethro Compton, author of an adaptation of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance; and the successful Frontier Trilogy, which premiered respectively at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and Park Theatre in London. Yet, the Western still remains a distinctly American genre, with many notable playwrights writing plays about the lasting impact and mythology of the American West, including Robert Schenkkan’s epic Kentucky Cycle; Sarah Ruhl’s Late, A Cowboy Song; and Marcus Gardley’s the road weeps, the well runs dry.

It’s true that the Wild West has largely disappeared, although some still say it can be found by looking hard enough at the deep pockets of America. Some of these pockets are nestled in the land, while others are buried in our national character. One of the last great vestiges is the stage, which slowly and silently preserves our continental mythology. For as long as the West lives on in performance, it will never truly die.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here