Re-framing and Re-containing

Can We Really Ensure Safety in the Rehearsal Studio or Classroom?

I have been thinking about how we, as practitioners, almost compulsively talk about “safety” in our work, particularly in the studio or classroom, as though it is embedded in what we do. Safety is ubiquitous in our vernacular; we ensure it almost by reflex. What is safety, though? What are we really trying to get at when we talk about “safety?” Can we actually ensure it? Isn’t education and art-making intended to be risky? If we are taking risks and growing, can we ever be truly safe?

I began thinking about this with the kerfuffle last spring about the idea of using “trigger warnings” in classrooms and the question of when protecting students in advance of challenging material goes too far. As a self-proclaimed Social Justice Warrior, as a queer woman (thus, a member of intersectionally marginalized groups), and as someone who has experienced sexual violence, I appreciate the idea of a “trigger-warning.” When I’ve been “trigger-warned,” however, I usually sally forth and click on the link (or whatever I have been warned against) and wade into the difficult material (though I rarely read the comments—I’m not that brave!). Sitting inside complexity and difficult conversations has helped me become more resilient. It has helped me to become a better self-advocate. Yes, sometimes I collapse under the pain of history or previous experience. But rarely. And I can always pull myself back to the present.

I propose that perhaps “safe space” is a misnomer when, in fact, we are talking about a “supportive environment.”

Last month, I attended the Mid-America Theatre Conference (MATC) in Kansas City, Missouri. Attending a handful of the panels on theatre pedagogy, the topic of “safety” came up multiple times and I found myself bristling at the word. Perhaps this was because, as one panel participant suggested, education is inherently unsafe, fundamentally designed to challenge one’s sense of boundaries (This may have been Dr. Martine Kei Green-Rogers—correct me if I’m wrong). Or perhaps my reaction occurred because over the past year or more, I have done more and more theatrical work in prisons, in which safety is, at best, a mirage. While I have felt “safe” facilitating work in this context, as have the participants, at any moment, something—a shakedown, lockdown, pat down—could occur that would upset this (naïve? utopic?) idea of safety. And the idea of a “safe space” also seems misidentified since the notion of space is complicated by the architecture designed to punish, contain, and separate (this came from a post-panel conversation with Karen Jean Martinson). I suppose the pepper spray I was required to wear on my belt and the radio I was instructed to carry should have heightened the lack of safety, but instead I was caught up in rehearsals in the perception of safety. By that, I realize now, I mean the temporary, communal imaginary: the opening up of possibilities previously unimaginable; a perceived quality that we could travel, individually or collectively, to emotionally dark and painful places and come out the other side with our sense of self, and our sense of community, still intact.

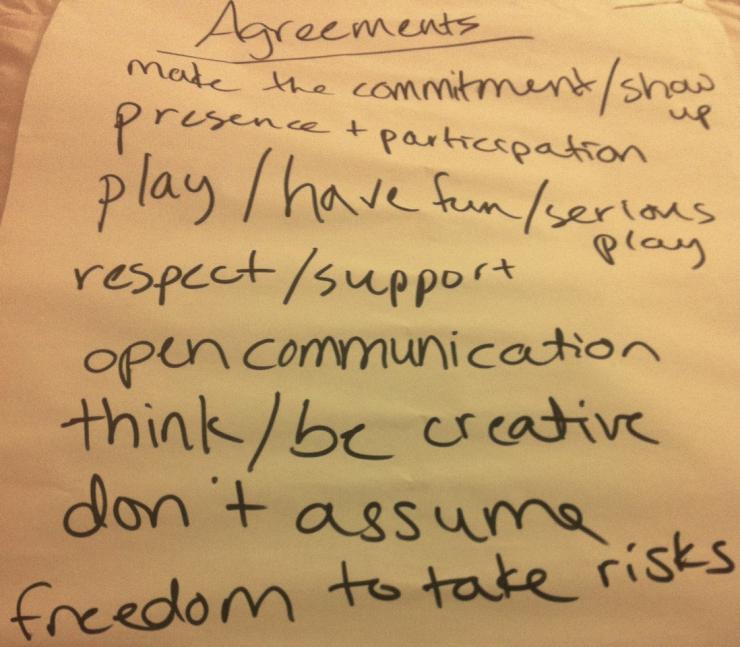

I propose that perhaps “safe space” is a misnomer when, in fact, we are talking about a “supportive environment.” Since I began directing several years ago, I often take a little time at the beginning of the rehearsal process to establish “group agreements.” This practice has transferred to my work in college classrooms and in prisons. Upon reviewing these lists from the past few years, I’ve compiled the most common agreements in order to get at what we mean by “safety.” This list is far from exhaustive and I urge you to add your own agreements in the comments below (and I promise I will be brave enough to read the comments, in this case):

- What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas. Essentially, that the group must maintain some level of confidentiality outside the container of the rehearsal studio or classroom. The nuance of confidentiality differs between groups.

- Don’t assume. Give one another the benefit of the doubt.

- Listen. Actively and sincerely.

- Share. Generously and without attachment.

- No shame/no blame. We can deal with conflict openly and directly as a group. We can make space for handling harm, should it occur, but we cannot and will not promise that you won’t be hurt or challenged.

- Practice pluralism. Recognize that our group may include a diversity of opinions, ideas, backgrounds, experiences, aesthetics, and social identities. This is cause for celebration. We can preemptively identify the things we may feel touchy about so as not to offend. Also, see #2.

- Practice active and explicit consent. Recognize that some activities within rehearsals are risky (physically and/or emotionally) and encourage ensemble members to be risk-aware, choosing whether or not to engage.

- Self-care. Okay. This is not usually on the lists, but I think it should be. As facilitators, we can model and encourage self-care. This provides extra protection from harm and increases resilience. It prevents burning out and other masochistic tendencies endemic in our discipline.

- Have fun. Self-explanatory. And essential.

In a mutually supportive environment, we develop a temporary community in which folks maintain increased mindfulness of their colleagues, take responsibility for their language and behavior, and seek to resolve conflict and injury in a respectful manner. Maintaining comfort has never shown up on any of these lists, which implies that ensembles implicitly recognize that comfort cannot be guaranteed, nor should it be desired. Play or fun shows up on almost every list. And that, my friends, is the name of the game, even—and maybe especially—when dealing with difficult subject matter. Play is enabled when supports are in place. Safety not required.

In the past, I have been guilty of perpetuating this cult of safety. I have been the Queen of Safety, in fact, proclaiming, promising, and promulgating that which I had not heretofore examined. But no longer. From now on, I call upon myself to practice a meta-mindfulness; choosing my language carefully when speaking about the sensitive creative work that happens in rehearsal and educational processes.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Agreed. In the arts, safety means something just a bit different than it does in, say, a prison or on a playground. In the arts, safety does not mean "protection from _______" nor would we want it to. When we talk about a "safe space" in a rehearsal room, we are essentially giving each other permission to explore scary, risky, socially problematic and trigger-y ideas within a controlled, altruistic environment. And that environment has to be developed explicitly; "agreements" are essential. No one should ever wonder what will happen if things get hard in a rehearsal space. Doing this, we give ourselves permission to prod those triggers in the presence of artists who are there to guide us, challenge us, uphold us, push us further, and catch us when we fall. In my experience, though, none of this matters without extending the same generous gesture of caretaking to the audience, which is the ultimate receiver of the theatrical gift. We can present plays that are deeply uncomfortable, but the audience must understand that we are giving them a "safe space" to consider the challenges presented to them in the course of evening. Audience talk backs, dramaturgical displays and presentations, tools for online post-show conversations, actively and personally getting to know your regular audiences ... all of these help the audience understand that we are not telling difficult stories simply for anonymous provocation.

I would love to see the topic of safety as a Thursday #howlround discussion. I have been wondering about content notes for the audience, as we sometimes warn for gunshots and strobes....

I, too, have been the one crying out for "safety" in this work. Being a former mental health counselor, I somehow felt it was my responsibility to be hyper-aware of the emotional consequences of applied theatre work. Perhaps, more accurately, I was just more aware of that aspect because of my counseling background. At any rate, I was often concerned when colleagues would jump into various activities that brought up emotional reactions that were then left un-discussed/unprocessed or derailed the process as the focus shifted to attending to that participant(s)'s needs.

It was during a session in Brazil with Augusto Boal several years ago that helped me shift my thinking about safety -- and your numbers 5-7 resonated with what he talked about with respect to safety. Boal had been asked about safety in his work and essentially replied that there was no safety in his work. While this seemed alarming at first, taken in the context of the work he has done and the experiences he had gone through as a result, it seemed clear that his response was the only logical one he could give. However, as the discussion continued, I got the sense of there being two different kinds of safety and really two different definitions for the work, much as you've outlined here. And that's how I now approach doing applied theatre work as well as any theatre work.

In the first type of safety, we're talking about the facilitator establishing that he or she will do their best to ensure that the participants can participate fully in the activities -- providing a safe environment as well as collaborating on or simply setting ground rules that establish how the work will progress and how participants will treat each other. In other words, the agreement that you have discussed.

The second type of safety is the one that we want to actively avoid -- the complacency of not taking risks in the work, of not pushing one's boundaries, of not being open to new ideas and new ways of thinking.

While some might divide these out as physical safety versus emotional safety, I think it's more about a foundation of safety (the first type) from which then participants are free to soar. The idea of roots and wings comes to mind -- the first type of safety provides the roots that ground the work (theory, technique, agreed upon guidelines for how the work will be done and how participants will treat each other) while the second type of safety, when willingly laid aside, is the wings that let the work take flight.

For me, by doing as you suggest -- laying the foundation for the work by establishing a set of agreements -- allows for the freedom to explore, play, push boundaries, take risks, etc. because you can always come back to that core safe environment.

Having said that, I also recognize that exciting and innovative work can come without that safe base. I am less comfortable doing that type of work, although I know there are others who want to work from that place. As long as all the participants know what they are signing up for, that's certainly their prerogative.

I also recognize that setting those ground rules is no guarantee that all participants will buy into or always follow the agreements. There is no perfect system and no way to ensure that, for example, the work stays in the group (should a group member decide to break that expectation). Still, for me, it's important to be transparent about the fact that working as a group is exciting and inspiring, but also can be challenging, exasperating, and conflict-producing so that establishing a foundation from which the work will be built can help ground the work and reduce those challenges so that the inspiration has a better chance at soaring.

Thanks for sharing your ideas!

Thank you for distinguishing emotional and physical safety, and for bringing up the subject at all. In my experience, the safety in the rehearsal room is often given mere lip service. I've known theatre professors intent on "breaking" young actors to tears - what was their intention regarding the emotional safety of their students? As for physical safety, I've been dropped on my back in the middle of live performance, because my acting partner was "moved in the moment" to drop me. I've argued with directors over the necessity of a formal fight choreographer when staging a sword fight. My partner has been facilities manager for several theatre schools. In one nationally prominent MFA program, a teacher instructed the students to screw the tumbling mats to the wall with a drill; at the end of class, the mats were pulled off the wall. And the next time they were used, a student received a wound that required an ER visit and stitches, from a screw left in the mat. And let's not get started on fire codes. So there is the taking of risks, emotional and physical - yes, I want to learn new tumbling tricks, at my age! I want to be emotionally vulnerable in front of many strangers! But there's also basic common sense. And the one does not trump the other. Too often, I think artistic risk is used as a get-out-of-jail-free card to ignore basic common sense, like keeping the fire exits clear.

P.S. Most actors don't have health insurance, which adds another dimension to the topic of staying safe.