Transcript:

Mike Lueger: The Theatre History Podcast is supported by HowlRound, a free and open platform for Theatre makers worldwide. It's available on iTunes, Google Play, and howlround.com.

Hi. Welcome to the Theatre History Podcast. I'm Mike Lueger. Many of us have favorite scenes and roles from William Shakespeare's plays. But what about moments like the happy ending of King Lear or characters like Miranda's sister from The Tempest? If neither of those rings a bell, it's because they come from productions of Shakespeare plays from the era known as the Restoration. There are a number of striking changes that were made to the original plays during this period, but there's also a much more complicated story behind Shakespeare's evolution of the Restoration stage. The Performing Restoration Shakespeare Project is trying to piece together that story through both research and performance.

Today, we're fortunate to be joined by Dr. Amanda Eubanks Winkler. She's an Associate Professor of Music, History and Cultures at Syracuse University. She's also co-investigator on the Performing Restoration Shakespeare Project, and in that capacity, she served as a consultant for a professional production of a Restoration era version of Macbeth. Amanda, thank you so much for joining us.

Amanda Winkler: It's great to be here.

Mike: Could you please tell us more about what the Performing Restoration Shakespeare Project is and who's working on it?

Amanda: I am the co-investigator of the Performing Restoration Shakespeare Project. My collaborator, who's the primary investigator Richard Schooch who is a Theatre historian at Queen's University Belfast, he and I wrote a grant and were fortunate to receive it, and we received a substantial grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council in the UK to investigate how Restoration Shakespeare, these really interesting, sometimes radical adaptations of Shakespeare were performed during that era and we felt that they could also be really appealing for audiences today in part, because of the substantial amount of music and dance that were added into these productions, into some of these Restoration Shakespeare Project productions. We decided to test this out and the Macbeth production was part of that process of testing.

Mike: Now, when we talk about the term "restoration," could you just remind us briefly, what does that term refer to and what's so significant about it with regards to the history of Shakespeare on stage?

Amanda: Well, the restoration is a period that stretches from 1660, and if you want to be generous on the other end, to around 1714. That's when Queen Anne died, the last Stuart. Before the Restoration, of course, there've been a civil war. The Theatres have been closed in 1642 by the Puritans, and they were shut until 1660. After the Restoration occurred with the restoration of King Charles II to the throne, then the Theatres were also reopened and new things needed to be written very quickly.

So, what William Davenant of the Duke's Company did is he took some of Shakespeare's plays and he began adapting them for the new taste of his audience. The audience were craving spectacle, some of them thought that Shakespeare's language was antiquated and old-fashioned. So, he changed the language and brought it up to date. He added in musical numbers that had not been there before. Davenant during the 1650s had been engaged in experimenting with opera. He was really interested in bringing some of these operatic elements into the Theatre and into Shakespeare.

For all of those reasons, Shakespeare was an easy kind of person to use because he had some of these plays in his possession and could quickly adapt them, because they needed to have stuff to put up after the closure of the Theatres. Also, it's interesting to think about that Shakespeare is in a sense was the first generation to perform Shakespeare after Shakespeare. It's interesting to think about the ways that they were approaching him. They certainly didn't view him as this sacred thing that could not be touched and could not be adapted. The acknowledged he was a great playwright that's why they wanted to put on his plays. But they didn't view him as being the sacred bard at that time.

Mike: One of the most significant changes from Shakespeare's time to the Restoration is that women are now allowed to perform on stage. Could you tell us how that affected the ways in which the plays were performed?

Amanda: It certainly did affect the ways. Having women on stage certainly did affect the ways that Shakespeare was performed. For example, you already mentioned that in The Tempest, Miranda has a sister. She has a sister, Dorinda. He's interested in adding, in that case it was a Davenant and Dryden adaption of The Tempest. They were interested in adding in more roles for women and in the case of the Macbeth we did, they expanded roles that were already there. The role of Lady Macduff in Macbeth is substantially larger in Shakespeare's play and she has a lot more to do, and in part that's because you have women playing women's roles. That is certainly something that Davenant was wanting to do and other Restoration playwrights as well.

The patent, the theatre patent that kind of allows for the women to be on stage, it says something and this is a slight paraphrase, but it says something along the lines of "In order to have a more natural representation of human life, we're going to allow women to play women's roles." Part of this was because of again, practicality. On the whole system for training up boys to perform was gone. Those nurseries that allowed for the training of boys was gone. That's not to say that there weren't sometimes this residual practice of them playing women's roles. For example, Edward Kynaston still played women's roles in the early Restoration, but gradually that older practice with some plays having Kynaston was kind of long in the tooth to be playing women's roles, honestly. But he did in the early Restoration and [Pete 00:07:07] says he looked beautiful as a woman. But, by and large, women were playing women's roles and as a result Restoration Shakespeare responded and provided more for them to do on stage.

Mike: Restoration Shakespeare opens up these wonderful, new casting opportunities for women. It also features very different kinds of theatrical venues from what we saw in Shakespeare's time. Could you tell us a little bit about the theatres and how the different style of theatre affected the performances?

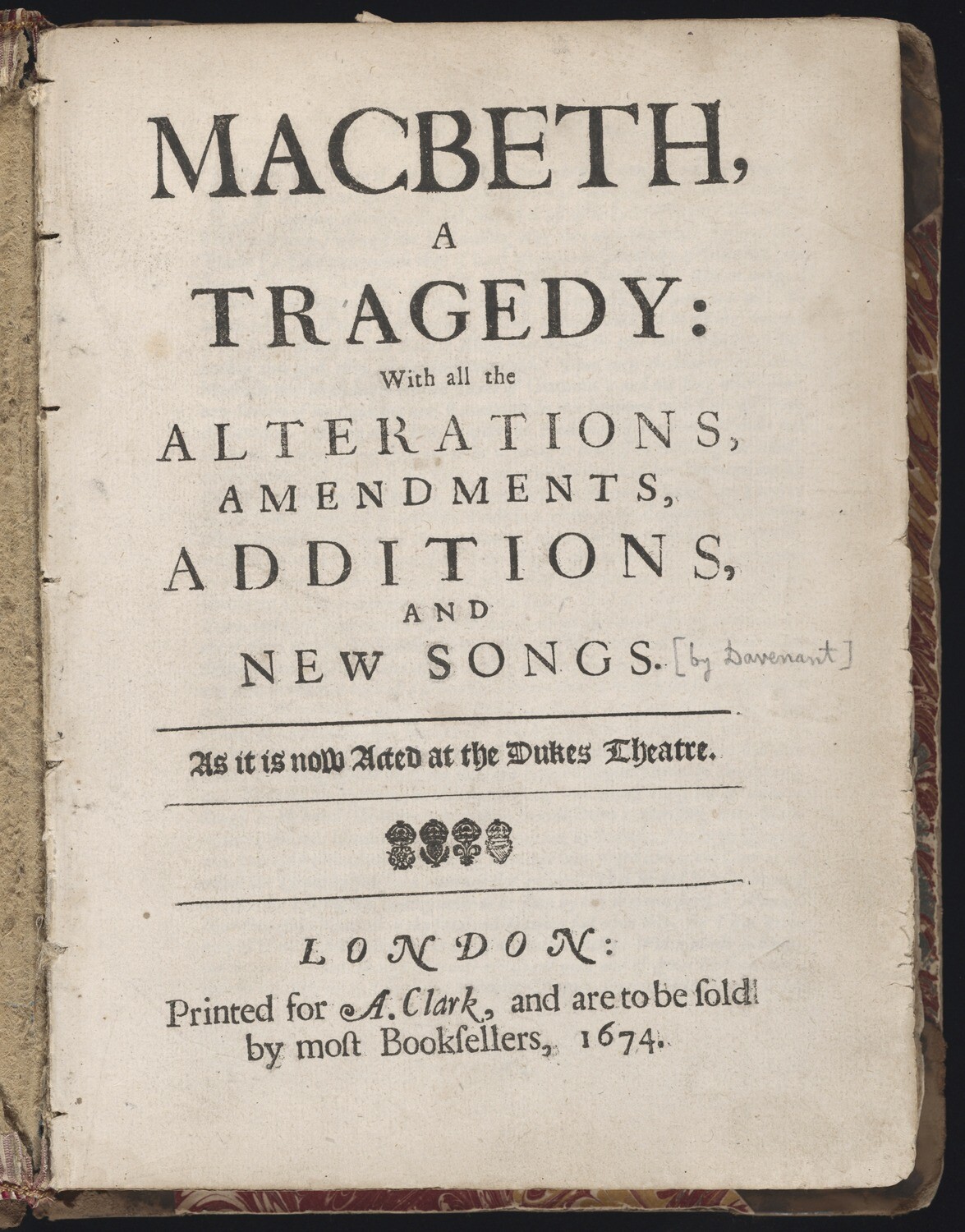

Amanda: I'll speak directly about Macbeth. Macbeth was first performed in 1663 or '64, but we only have a Cawdor from 1674. The printed version that we have is from 1674. We know that in the 1670s production at least, they added in a substantial amount of spectacle and the reason for this is because the Duke's Company, which was the company that Davenant had founded had moved to the Dorset Garden Theatre. The Dorset Garden Theatre had all the mod cons, it had all of the gear of Baroque stagecraft. It had machines. It had the ability to fly people and they use that for the witches. They had trapdoors. Multiple trapdoors, so people could sink into hell and then, come up from the ground.

They had the shuttering [inaudible 00:08:32] system which was something that Restoration Theatres of course have had earlier that allowed for a scenery to be brought in from the side and quick changes, quick changes of scenery. It was also a proscenium stage where it was different than what had come before. All of those things shape what people saw on stage and it's part of the reason, but especially after Dorset Garden Theatre in the 1670s spectacle was a big part of it as well. There has been some recent research done on the Kings Theatre that suggested they also did have some capacity for doing spectacle, but certainly we know that the Dorset Garden Theatre was the one where they put in the big shows, at least in 1670s. They put big shows in there that included spectacle, music, and dance. That was one of those shows.

Mike: Now, we've been talking about all the things that were going on stage and your projects takes pains to emphasize that it's not just examining how Shakespeare's plays get rewritten during this time period. With that said, it's hard to avoid pointing out that there's some pretty drastic changes that take place to some of these plays. Could you tell us about some of the more significant rewrites; who made them and why they did those rewrites?

Amanda: The Restoration was interested in symmetry. In the case of the Dryden-Davenant Tempest, some of the characters are added in, so you have paired couples, so you have symmetry in terms of the love relationships. You have one pair of couples here, you have Miranda and Ferdinand on the one side, and then on the other side, you have Dorinda and Hippolito. Hippolito is a man that has never seen a woman, right? It's kind of this pairing with symmetry. Likewise, in the Restoration Macbeth, Davenant's adaptation, you have symmetry there as well. The Macbeths are very much cast as the bad couple with this inappropriate relationship in their marriage. Actually, at the end of the play, Lady Macbeth calls out her husband and says, "You know, this isn't my fault, really. You, by the charter of your sex, you should have governed me. You shouldn't have listened to me." It got a laugh every night, that line.

The Macbeth couple is the bad couple with the bad marriage, in which the man isn't behaving according to Restoration notions of gender hierarchy it's not doing the right thing and it's listening to its life inappropriately. On the other hand, the Macduffs are the virtuous, good couple. Davenant is at pains to explain some of the things that don't make sense in Shakespeare's play because there's some plot holes in Shakespeare's Macbeth. So, why does Macduff leave and take off, and leave his wife to get murdered? Well, Davenant explains that he doesn't think it's possible at all. Macduff doesn't think it's possible at all that Macbeth would be so horrible as to kill a woman and children, but of course, Macbeth is just that horrible.

Davenant is trying to fill in some of the logical gaps and he also was interested in kind of these symmetrical structure, so a good couple on the one side versus bad couple on the other side. Lady Macduff is this incredibly virtuous woman. She sees right through the witches. There's an added scene for the witches in which the Macduffs see them, they're singing and dancing on the [inaudible 00:12:04]. She sees right through their nonsense. It's like, "Don't listen to them. You shouldn't even be scared of them." She's a very perceptive woman, but again, this interest in symmetry, filling in gaps and plot holes, and adding in things like music, dance, and spectacle in the case of Macbeth or The Tempest, the Restoration revisions of those plays.

In terms of the happy ending in [inaudible 00:12:29], he clearly didn't want it to have that tragedy at the end. He wanted to subvert it in some way. So, sometimes things like that happen as well. Oftentimes in the Restoration is to communicate a moral message. At the end of Davenant's Macbeth ends with Macbeth dying and saying essentially, "Farewell, vain world and what's most vain in it. Ambition!" I'm going to tell you straight up what the take-home message. One of the things that as we were working on Macbeth that was interesting is at first, the actors fell through some of the subtlety of Shakespeare had been erased by Davenant's revisions. But, as they played it and as they saw the way that music and these other elements worked with the text, they realized that the complexity had just shifted, and that it moved away from text into more of the multimedia areas of the play, so its spectacle, potentially and we did try to have some spectacle in our Macbeth and the music.

Mike: Yes. You mentioned the music and I understand it played this very important role in these performances. Could you tell us more about this and really sort of how it changes the experience of the play?

Amanda: It entirely changes the experience of the play whether it's the musicalized Macbeth or the musicalized Tempest, but I'll focus mostly on Macbeth for our purposes here. Macbeth, of course is a tragedy. But what happens when you introduce music particularly the kind of music that was used for witchcraft, to portray witchcraft on the Restoration stage and often, to modern ears does not sound particularly menacing or scary and that's because we're used to thinking about nineteenth century symphonic language for how to portray fear or scariness. Then, some of that language was taken into film music. So, we think, "Oh, nasty, dissonant music that's scary," or even later kind of Bernard Herrmann in Psycho. It's like, "That's scary." That's the stuff that is kind of promoting fear, kind of scariness.

The witches music doesn't sound like that at all. So, automatically you have this layer of complexity that's introduced. Part of the reason why though in the Restoration, they wanted to have these musical scenes and these scenes involving dancing, partly to do with the King. When he was in exile, he'd been in France and he'd seen Louis XIV cool things that he was doing there with music and dance, and he thought, "I want some of that." The problem is Charles was pretty cash poor and so, he had to outsource to the public Theatres. That's one of the reasons why it had to do with pleasing the King, and the King's aesthetic, you have the incorporation of all of these music and dance into the Restoration Shakespeare plays.

In general, the Restoration Theatre was a good, musicalized Theatre. There were loads of songs in the plays, not just in Restoration Shakespeare. The music in terms of Macbeth is located in the scene for witches. Part of that is because the English stage, it had this desire to be rational. They never really embraced Italianate opera where you're singing all the way through. They thought that that was crazy, "Why would people sing all the time?" But, if you're a witch, you're a supernatural. You're already outside the realm of reality, in some sense, so it's appropriate for you to sing. Now, the witches songs in the Macbeth production we did were by a composer John Eccles who probably wrote these settings of the songs for the 1690s production.

What Davenant did when he adapted it in the 1660s is he took some songs that had already been interpolated into Macbeth from very early in its performance history, because if you know Shakespeare's portfolio, you know that there are songs in Macbeth. Those songs were taken from Thomas Middleton's play, The Witch and were being performed in Macbeth as early as 1515 or 1516. Macbeth was already a musical play from very early on in its performance history. Then, so he kept those. He kept the [inaudible 00:17:06] Come Away and Black Spirits and Light, Davenant did and then, he added in Act II Scene V this addition scene of music in which the Macduffs see the witches on a [inaudible 00:17:20] singing, dancing, and celebrating the [inaudible 00:17:23] of Duncan.

Again, they sound pretty happy about it. They're really excited. But, they're evil creatures, so of course they're going to be excited and happy about kings bleeding. It changes. It changes the way that you perceive the play and it also gives more weight to the witches because they have these big, operatic musical moments. Samuel Peyps, he loved this musical version of Macbeth and he called it "a strange perfection in a tragedy to have this." It does present a difference of tone, because you have tragedy, tragedy, tragedy, singing and dancing witches, tragedy, tragedy, tragedy. For a modern production, you have to think of ways of making that work and making it understandable for audiences that, "Oh, the reason why the witches are singing in this way is because they're happy about something perfectly horrible." They're not just cute, although they are cute, too, but.

Mike: You've been talking a little bit about how this is all worked in performance, but I'd love to hear more about sort of performance side of this project. What sort of events have you organized and what are you exploring through these performances?

Amanda: We feel, Richard and I feel that if you look at the Cawdor for example, since there's only four Cawdor of Macbeth, it dies on the page. You cannot understand it because all you get, all you see is you get hung up on, "Oh, my gosh. He changed that speech. It's not "Out, brief candle." It's "Out, short candle." You get hung up on ... and a lot of critics have gotten hung up, and have just completely dismissed this repertory because they're just looking at it from a textual perspective. What we feel, and the reason why we're doing this project is we feel strongly that in order to understand what they were doing in the Restoration, you have to perform in it and you have to put in on stage, and you have to put it on stage with all of the constituent parts.

You have to have Davenant's text in this case, in the case of Macbeth. You have to have the singing and dancing witches. You have to have some kind of spectacle, however you choose to do that in the modern Theatre, it's up to you but you at least have to allude to some of the spectacular elements of the Theatre, and if you do all of those things, then you start to understand the dramaturgy of the piece. But what happens is, is when you read the text, you don't hear the music, you don't see the spectacle. So, you miss out these crucial bits of information that people had in the Restoration Theatre when they saw it.

That's not to say we're interested in doing some kind of museum piece. We're not. But, we do feel is if you have to retain those elements and perform them in order to understand it. Our kind of proof of concept of this was back in 2014, the Folger Shakespeare Library asked Richard and I to co-lead a workshop for scholars called Performing Restoration Shakespeare and we chose scenes from the Davenant Macbeth with a different musical settings and with different ones we could choose from that he kept composing new music for this thing. Richard leverages for that and we did scenes from the Restoration version of Measure For Measure which was performed in 1700, and that was done by Charles Gildon.

What they did is they chopped up Dido and Aeneas, and stuck it into Measure for Measure, and it actually worked really well but you wouldn't know that unless you try to stage it. It's like, "Wow. Wow. There is this kind of this connection between Isabella and Dido, that it comes really evident when you stage it." We did that and it worked really well and it worked well embedding scholars in the process because that's the other piece of Performing Restoration Shakespeare is we want to foster collaboration between scholars, Theatre historians, English literature scholars, and music colleges and bring everyone together and collaborate, and use historical knowledge as a stepping off point, but not as a shackle.

In other words, we want it to be a point of departure or a creative father for then what we do on the stage. That was 2014. Then, we wrote our grant and got it. Then, we moved into the grant phase of the project and that has been running since 2017. Our first event was a workshop of the Restoration version of The Tempest which was done by Davenant and Dryden in 1667. We actually chose a 1674 version of The Tempest that was also done at Dorset Garden, and they revised it. It was Thomas [Chadwell 00:22:16] who did a revision of the Davenant and Dryden and added in more space for music. We did scenes from that version with music by Pelham Humphrey and John Banister, and Matthew Locke. That was a wonderful experience.

For that, it was a workshop performance that we did at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse in London, called the Shakespeare's Globe complex. I served as music director for that one and choreographer. We collaboratively do some stage direction. The way it works is we came up with a preliminary staging and then, Richard and I did collaboratively. Then, we presented that to the scholars and then, they gave us feedback and tweaked certain things with the actors, and the musicians, and then we put it up in the Wanamaker Playhouse for paying customers and then, the people in the audience also got the chance to react to our staging. Then, we tweak it again. We did two different performances in the Wanamaker up two different excerpts from the Restoration Tempest.

We learned a lot about best staging practices, things that work in a Theatre, things that don't work in a Theatre from that experience both kind of having our exchanges with the scholars and with lay people who just came along on an afternoon to see our Tempest. Then, of course we just finished with the full professional production of Macbeth at the Folger Theatre. As we've said, the Folger's been a longtime supporter of this project that it was Kathleen Lynch's brainchild at the Folger Institute for the initial 2014 workshop. It was a natural fit to do it at the Folger Theatre. The Folger Theatre, of course they have the Folger Shakespeare Library as a complex. It has the in-house Folger Consort, an early music ensemble.

They have a fully professional Theatre and they have the Folger Institute which is a great kind of infrastructure for scholars to work. We selected six scholars to be on our collaborative team. They were embedded in the rehearsal process for two weeks and we gave input. We had interviews with actors, one-on-one that would answer questions about Restoration Shakespearean Performance and what their experience was playing Restoration Shakespeare versus Shakespeare-Shakespeare. Many of them, the people who played, the actors who played Lady Macbeth and Macbeth have played those roles before. In fact, the Macbeth had just finished playing Macbeth, Shakespeare's Macbeth in Chicago and then, they had to turn around and learn slightly different lines for the Davenant Macbeth.

It was really difficult on Ian Merrill Peakes who played Macbeth. That was what we did with our six scholars. Then, Richard and I stayed on through previews to continue to be consultants available to the production team. But we did have a team of six scholars who used their knowledge as a point of departure. Again, for the creative team and we are fully-embedded in that process. Then, the professional production happens. Then, next summer we are doing a summer school and we're still thinking through location but we're going to have students come along to learn from Richard and I about frustration Shakespeare, staging practices, and will present scenes from The Tempest at that time. We're going to bring over personnel who were involved in the Macbeth production at the Folger Theatre as well to talk about their experience with staging Macbeth. That's going to happen next summer.

Mike: It's really great that you're able to get these in front of, as you mentioned, paying audiences and I'm really curious to hear what the reaction has been like. How do the audiences and to a large degree, the participants as well, how do they react to performing in and seeing these works in these unfamiliar contexts?

Amanda: t's fascinating to watch. I'll talk about each of the groups of people in turn. For the early music people, it's nothing new because some of those repertory, we perform anyway. It's not so unfamiliar because some of the best composers from the era were writing for Restoration Shakespeare. Sometimes, you do perform lost music from The Tempest or sometimes, you do perform bits and pieces of Restoration Shakespeare things. But, what is different is seeing it embedded in a full, dramatic production. That has not happened. So, for musicians, that's really engaging and interesting.

For actors, there are significant challenges, the challenges that emerged from the Macbeth production, and to a certain extent from The Tempest workshop as well. Many of the actors, that they're classically trained actors, they have played Shakespeare and they have played Shakespeare, and they have probably done Shakespeare's Macbeth or Shakespeare's Tempest. Then, being asked ... and they love Shakespeare's poetry, right? They love what he does with the poetry. It's incredibly complicated poetry. It's beautiful poetry. Then, they're asked to perform Restoration Shakespeare which just streamlines that poetry and rendered it ... has taken out some of its poetic beauty, potentially, because the beauty has gone elsewhere.

It's gone into music. It's gone into dancing. It's gone into spectacle. It's difficult for actors. But, the actors on the Macbeth production, it was fascinating watching the process. When they first came in, they had Shakespeare as a constant sort of, they were being haunted by Shakespeare and Shakespeare's texts. But as they got into the process, it became this new thing for them. One of the things, the person who played Lady Macbeth said, Kate Eastwood Norris was that at first, she thought, "Gosh. How am I going to do this? How am I ... " She kept thinking about the things that Lady Macbeth had lost and Ian said this to me as well, the person who played Macbeth, but in the act of playing it, she found new things and new registers, and new opportunities.

Kate ended up loving Davenant's Lady Macbeth. She said, she was a feisty lady, really feisty. In some cases, she was really straight up evil. But then, there was these other moments of vulnerability that she found. She really loved playing her. Davenant gave Lady Macbeth some really funny lines, actually. She loved kind of playing with that. Ian also, he found things about his Macbeth. He found a vulnerability in him that he hadn't kind of really found before, in other times he played the role. That was fascinating for him to be able to find that.

One of the things, too, that they played around with was playing styles. The production that we did of Macbeth was set in the Restoration era. We played around a little bit with using Baroque [inaudible 00:29:37] and should they do it, should they not do it. They ended up, there were some illusions to Baroque [inaudible 00:29:46] in what they did on stage, but they were trying to figure out ways of inhabiting these Restoration world because they were wearing Restoration clothing, and were they going to use a less naturalistic acting style? That was another thing that they played around with. Our production ended up not doing that in any kind of regimented way. But, I could see that being a mode that you could use for performing Restoration Shakespeare. It could work or you know, there are many different ways you can do it. But, those are some of the things that emerged.

In terms of audience response, for the Wanamaker Playhouse Tempest and for the Macbeth, we had audience surveys. We have a pretty good sense of what they were thinking. Some of the audience who came along to both thought, "Oh, my gosh. Shakespeare! What have they done to my beloved Shakespeare?" The missed some of the poetry of Shakespeare. For a lot of the audience though, the loved the music and these added things and they said, "This is fabulous. This could bring Shakespeare and his stories to a whole new kind of audience," and it makes, because they streamlined the language ... One person said about the Macbeth production, "I never understood some of these things. But in the Davenant Macbeth, he explains it, and it's easier to understand. So, I got it for the first time, like why these things are happening."

That was interesting to read as well. In some sense, Restoration Shakespeare, some people find it more accessible and more entertaining. That was interesting. They can get past the fact that Shakespeare's language has been changed, then they find other pleasures. The Macbeth production, we are very pleased by the critical response. It was overwhelmingly positive, by and large. It was very well reviewed. We were pleased to see that the critics mostly agreed that it was worthwhile and definitely stage-worthy. As part of the project, the Macbeth project, we had documentary filmmakers who came in and they filmed a dress rehearsal. So, we'll have some footage available in this documentary video. It's kind of the making of Macbeth, and that's going to be coming out sometime next year. That'll be available on our YouTube channel.

We'll have interviews with the actors about their experience participating, the music director, the producer and then, footage of the rehearsal process, interviews between scholars and actors, stuff like that. One of the things that we're hoping as a lasting legacy for this project will be that it changes the repertory. One other thing that Restoration Shakespeare asked us to do is to consider Canon formation, right? Shakespeare occupies an out-sized place in theatrical repertory especially with classical Theatres. There are many, many early modern plays and early modern playwrights that are worthy of our attention. What Restoration Shakespeare asked us to do through the lens of Shakespeare admittedly is to look at Shakespeare in a new way and to not view him as being this sacred object or this sacred thing.

What we're hoping is that things like the Restoration Shakespeare Projects will open up the repertory in interesting ways performing adaptations of Shakespeare from another time to see how people interacted with Shakespeare and what they found valuable about him and what frankly, they didn't like and decided to change. What we're hoping is that this will shift the repertory. We would like to see more performances of Restoration Shakespeare and more performances of other works that are viewed as being either difficult to stage or if you read them on the page, you think, "Oh, well, maybe I don't really get what this playwright was doing, so let's not do it." We would advocate for expanding the repertory, being adventurous in programming because it can really payoff.

The Folger Theatre sold-out Davenant's Macbeth. I just got the statistics yesterday. It sold at a 120 percent capacity, which means that people standing for every performance. They sold standing seats, so more people could get in. People are hungry to see new things. So, why not try something different. That's what we hope will be a lasting legacy of the project, that Theatre companies will take on these kinds of challenges and will think creatively about programming because it can really payoff both critically and at the box office.

Mike: We'll post a link to the Performing Restoration Shakespeare Project's website where you can learn more about the history of Shakespeare in the Restoration and discover additional resources and find out about upcoming events involving the project. Amanda, thank you so much for revealing this surprising chapter in the history of Shakespeare on stage.

Amanda: Thanks so much. It's been a pleasure.

Mike: If you'd like to continue today's conversation, please visit howlround.com and follow HowlRound and @TheatreHistory on Twitter and Facebook. You can also visit our website @Theatrehistorypodcast.net where you can find links to all of our episodes and e-mail your questions and comments about the show to [email protected]. A big thank you to the staff at HowlRound who make this show possible. Our music this week is Matthew Locke's Curtain Tune from a Restoration era adaptation of The Tempest. It comes to us courtesy of the Folger Consort, the early music ensemble in residence that collaborated with Performing Restoration Shakespeare for their recent production of Macbeth. You can find additional information about the consort in our show notes. Thanks as well to [Tippress 00:35:59] who designed our logo. Finally, thank you for listening.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here