This keynote, and other sessions from this event, were livestreamed on HowlRoundTV. View all videos.

Thank you for coming together for the Fourth Symposium on Doctoral Programs in Theatre and Performance Studies. My hope is that today marks the beginning of a collaborative field-wide effort to answer the following questions:

- What does the state of the academic job market look like?

- What skills are the graduates who come out of our programs developing and how are we shaping that process?

- How are we utilizing our graduate students’ time and energy in our doctoral programs in order to help them prepare for their future careers?

We will also have space in this convening to talk about the ways that we can better advocates for the value of PhD programs to university administrators, fundraisers, and to prospective applicants.

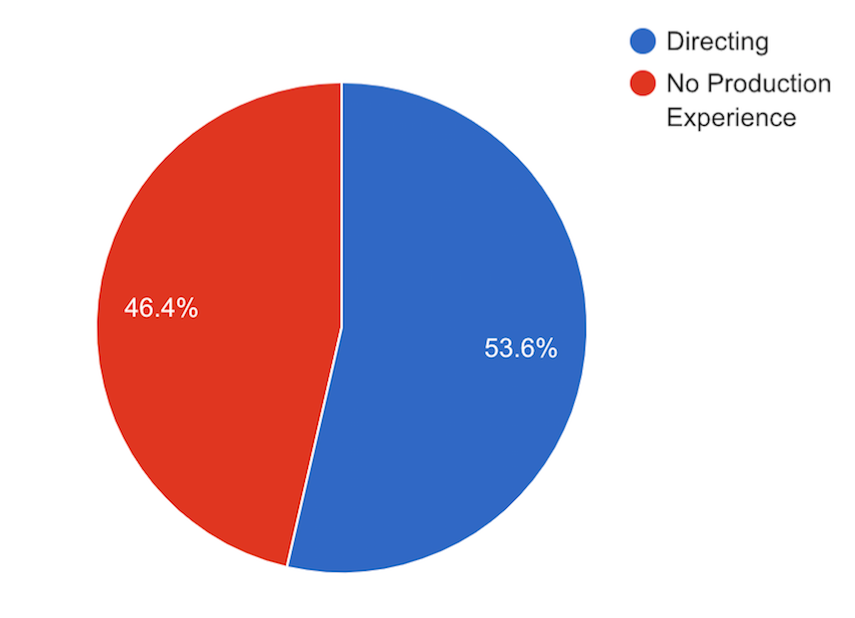

My knowledge of the academic job market is shaped by two experiences. The first was as a graduate student matriculating from Indiana University in 2009. As a first-generation college student, I came to graduate school with the expectation that a PhD would lead directly to a tenure-track job. During my time at Indiana, I regularly directed productions, wrote a dissertation on a topic that was of growing interest to the field, presented my research at the major conferences in the field, and published reviews in academic journals. Nevertheless, I spent three years looking for a tenure-track position, finally buoyed by professional directing and dramaturgy work accumulated through my employment with Cleveland Play House and Cleveland Public Theatre as well as an expansive adjunct portfolio in schools across Northern Ohio. Although I’m glad to be one of the fortunate individuals hired into a tenure-track job, I spent most of my time on the market wondering if I was doing something wrong. I never stopped to consider that academia in Theatre and Performance Studies didn’t have enough room to accommodate all of its graduates.

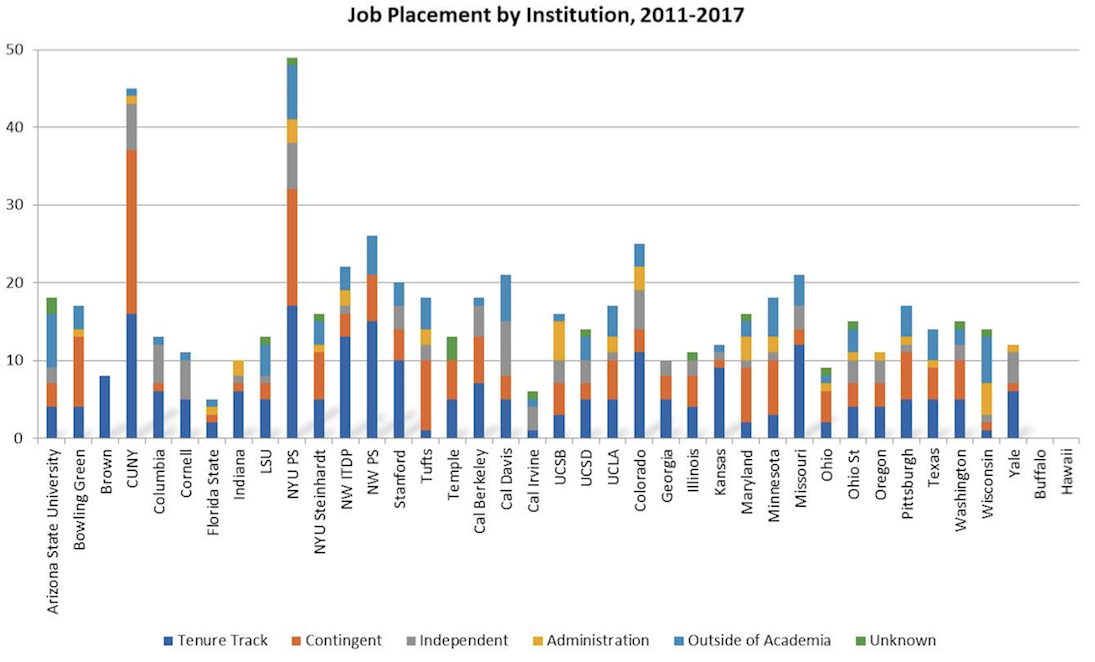

The next time that I felt compelled to think seriously about the academic job market occurred a little over two years ago when I became Director of Graduate Studies for the PhD program in Theatre and Performance Studies at Tufts. In order to take on the labor of preparing our graduating students for careers within and beyond the academy, I wanted to learn what trends were emerging from academic job postings, what institutions were doing the best at getting their students hired, and whether there were any commonalities among the programs that demonstrated repeated success in placing their students into tenure track positions. But this data, which is so essential to understanding how academic labor markets operate, did not exist. And because, as the members of my fantasy sports leagues will attest, I’m a stats nerd with a love of accumulating unusual data, I developed a couple of longitudinal studies to help me discover how many graduates of PhD programs are getting placed, how long it is taking students to find academic positions or leave the academy, what programs can do to better position their doctoral candidates for the academic job market, and what search committees are looking for based on recent hires in the field.

But as a scholar and theatre artist who has not applied for a non-academic position since I was an undergraduate, I knew that I also needed to learn how to help students find opportunities beyond the academy and I didn’t know where to begin. In traditional academic form, I started reading nearly everything that I could get my hands on, including books and essays by Susan Basalla and Maggie Debellius and Karen Kelsky in addition to blogs, web essays, and workshops that I found through social media. The totality of this work has helped me to develop a pedagogy and professional development course for first-year doctoral students at Tufts where we discuss academic and alt-academic job markets and how to prepare for career success in multiple sectors. Although I don’t claim to know everything about helping doctoral students market their skills, I feel more comfortable giving students the resources they need to think about multiple career trajectories from their first year in the program.

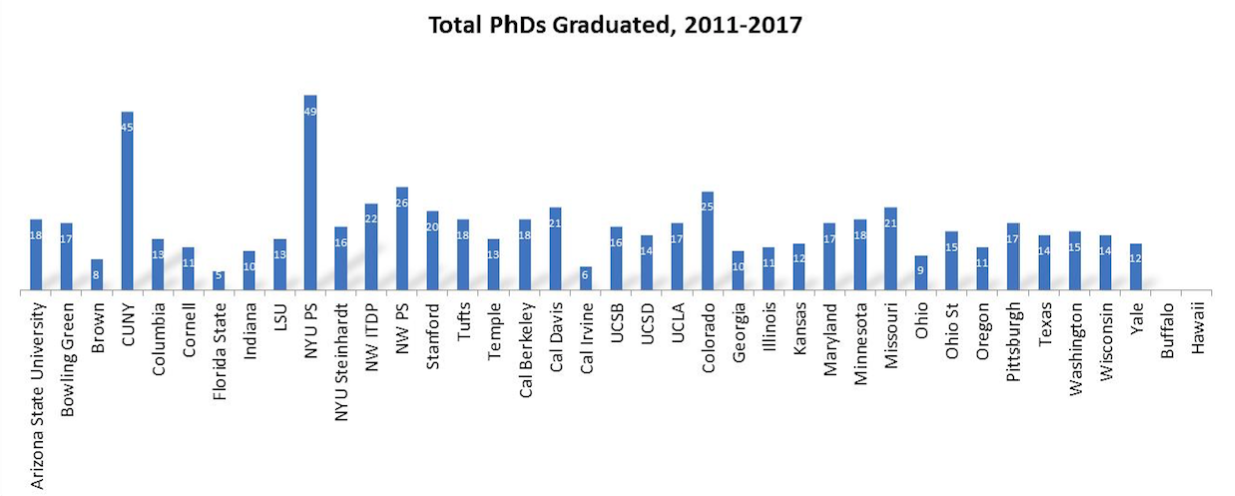

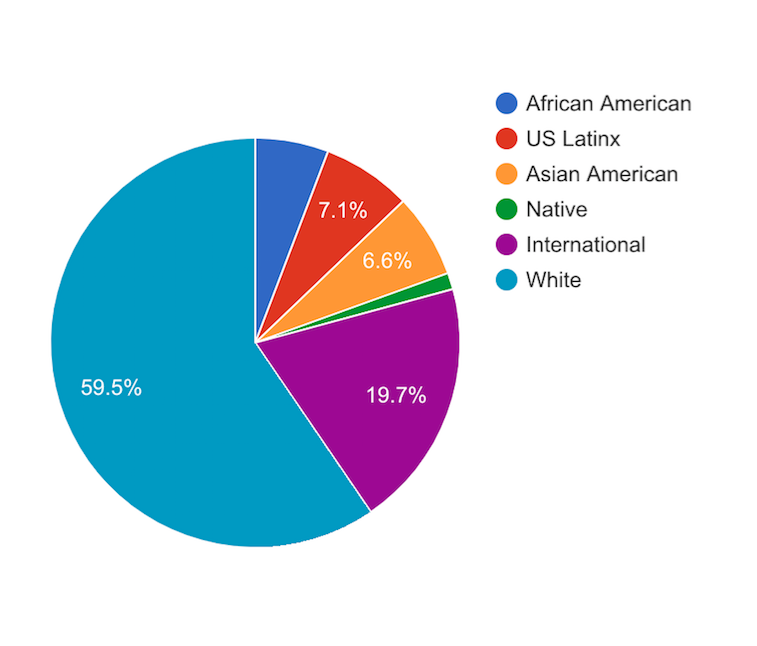

I want to take the time to share some broad data about how we are admitting, matriculating and training graduate students as a field, before moving to examine theatre and performance studies job ads over the past two academic years, and finally to look at the current careers and trajectories held by over 98 percent of the 633 PhDs who have earned degrees in our field from 2011-2017.

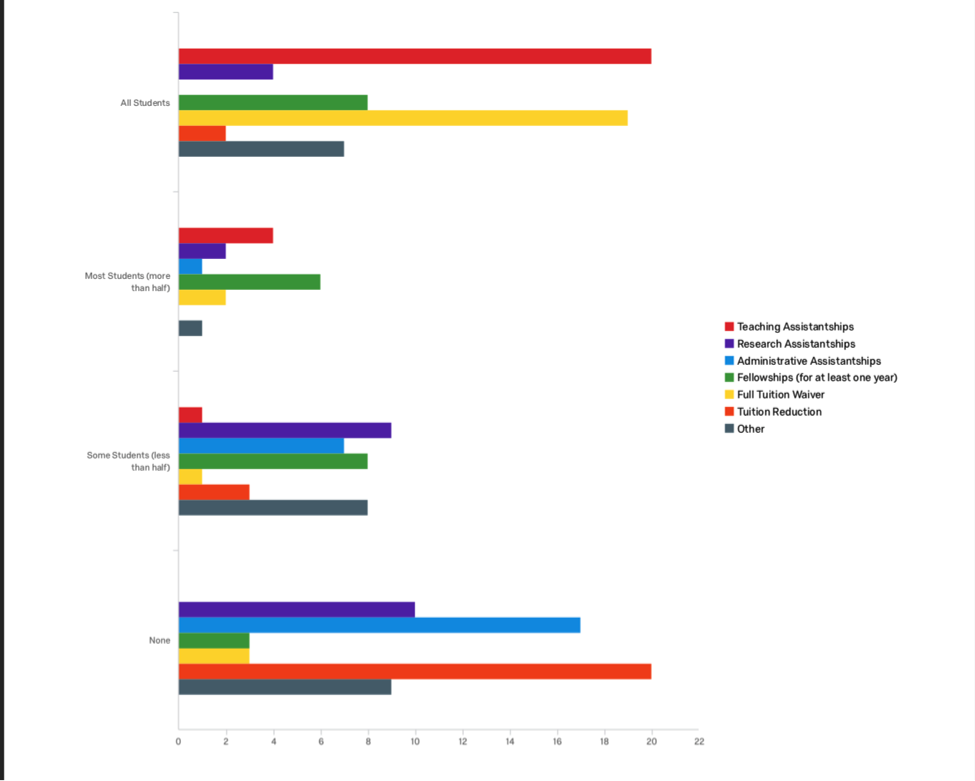

I’d like to begin by presenting information about who our graduate students are and how they are utilizing the time that they are spending in our programs, as revealed through the survey that many of us filled out prior to the convening in addition to my own supplemental research. In many instances, I’ll compare the results of this year’s survey with the results from the 2015 survey taken by those program directors who attended the Third Symposium on Doctoral Programs in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

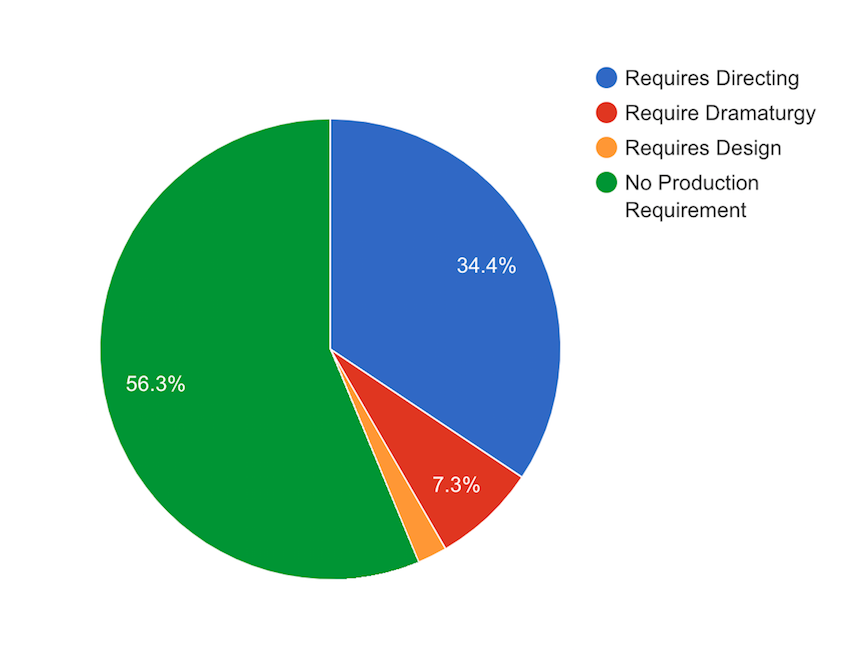

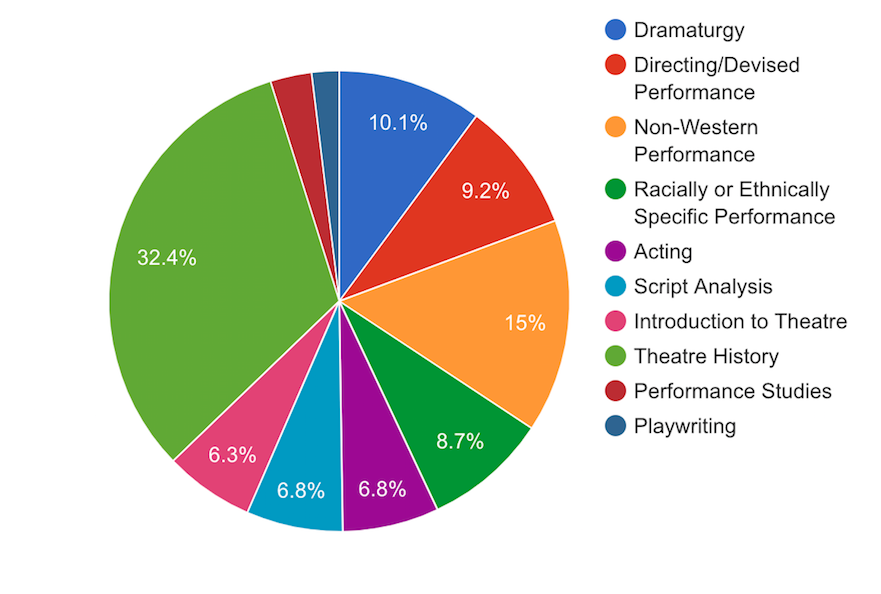

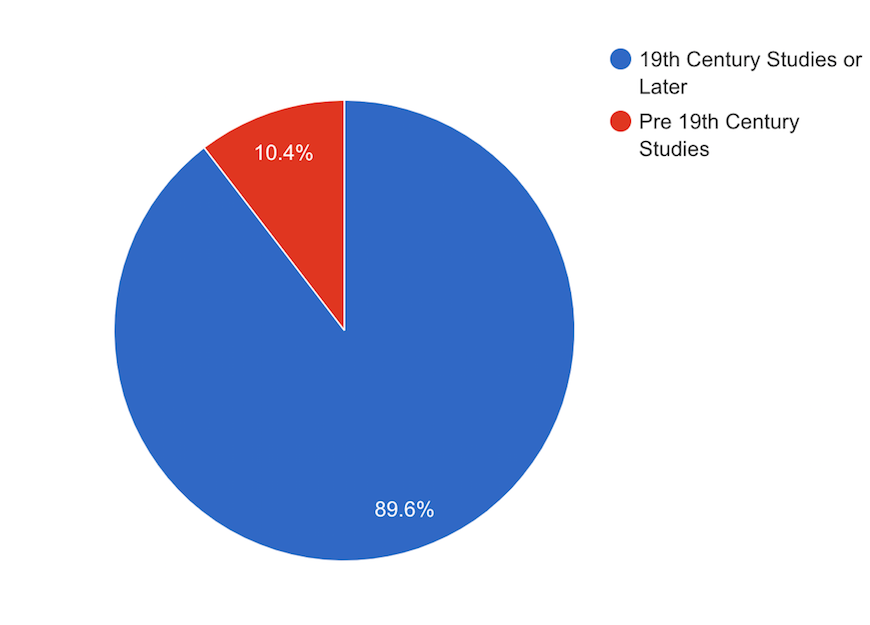

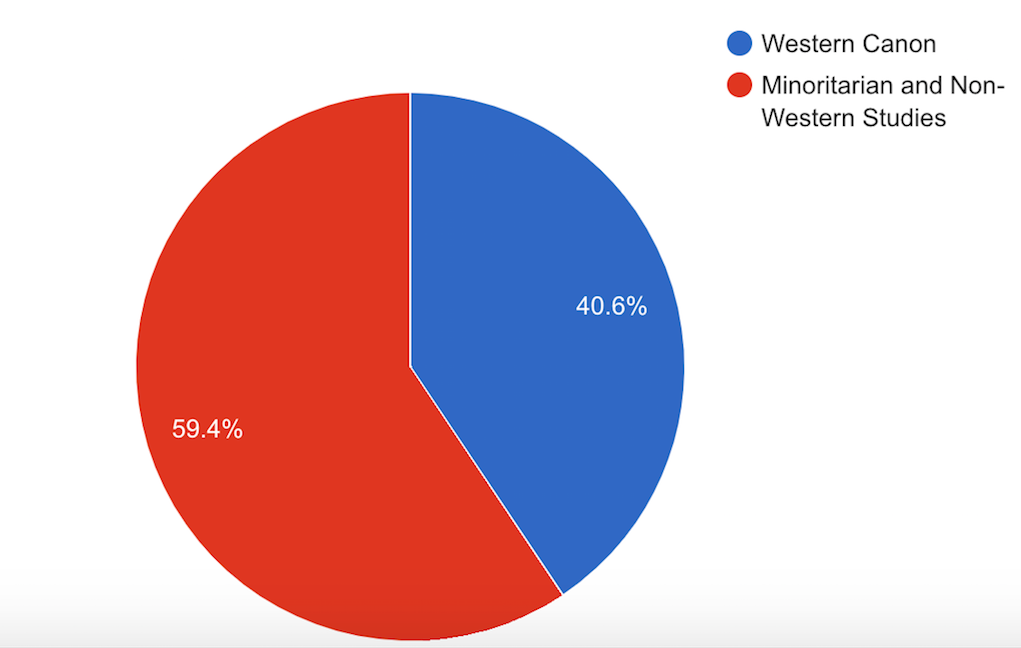

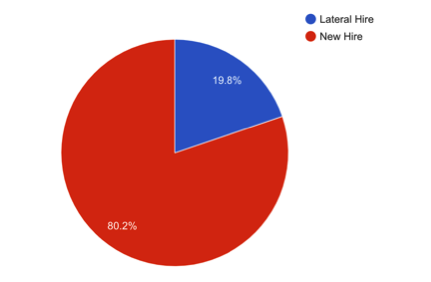

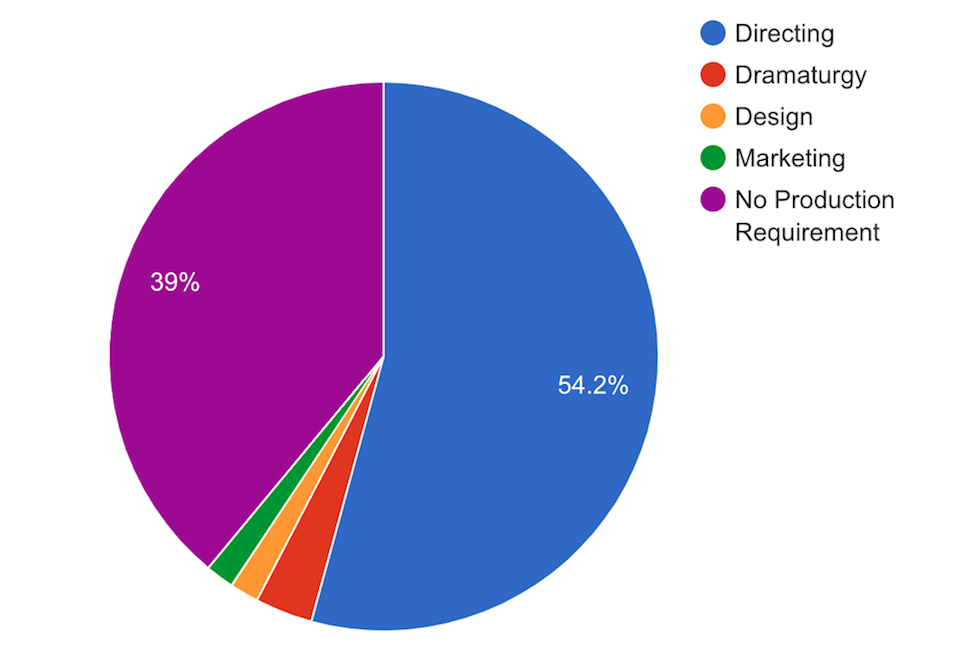

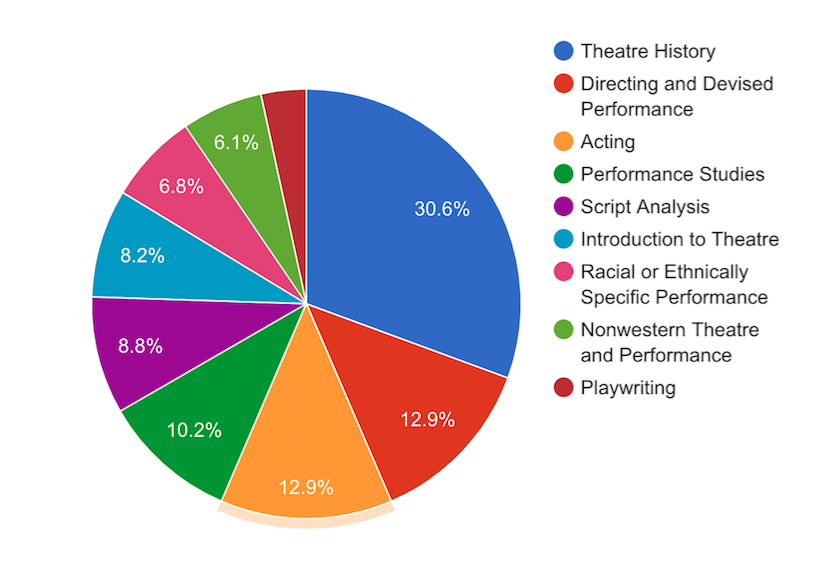

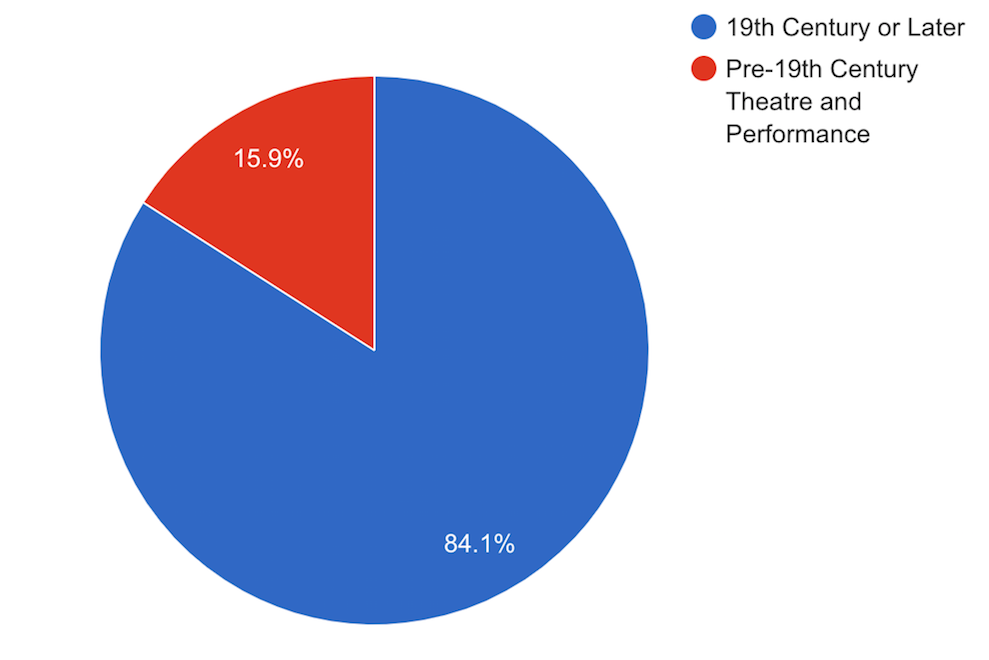

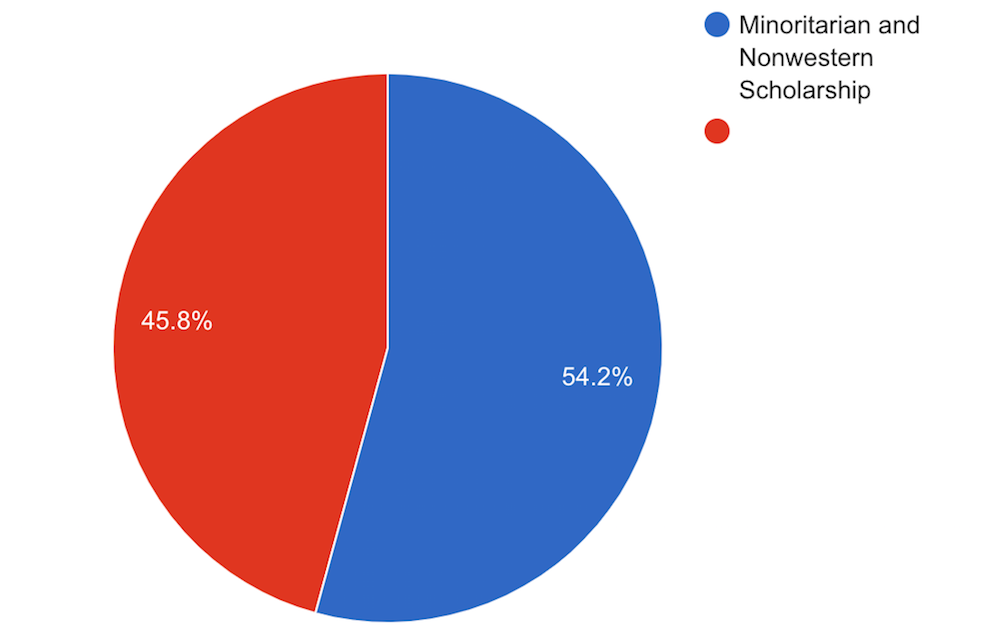

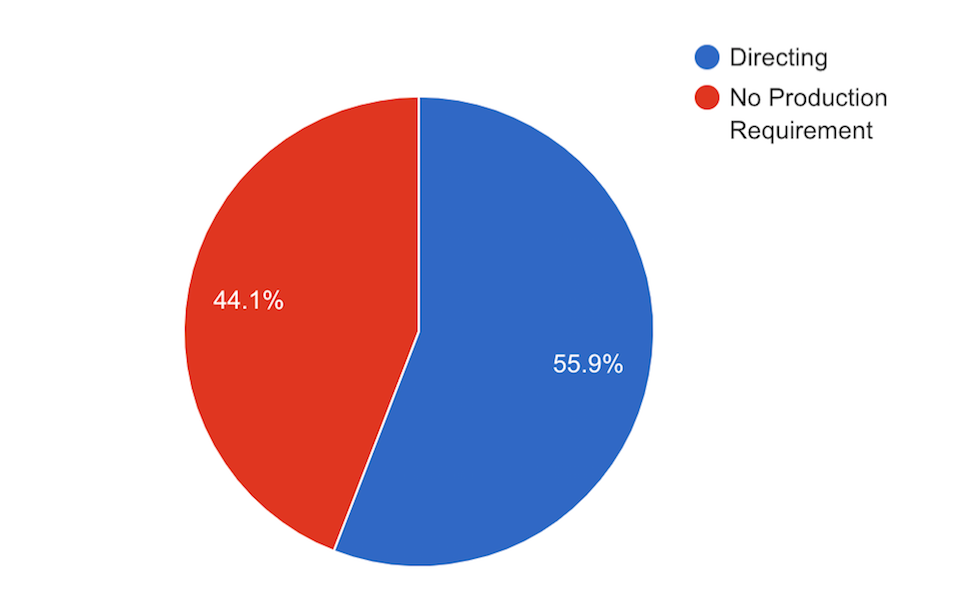

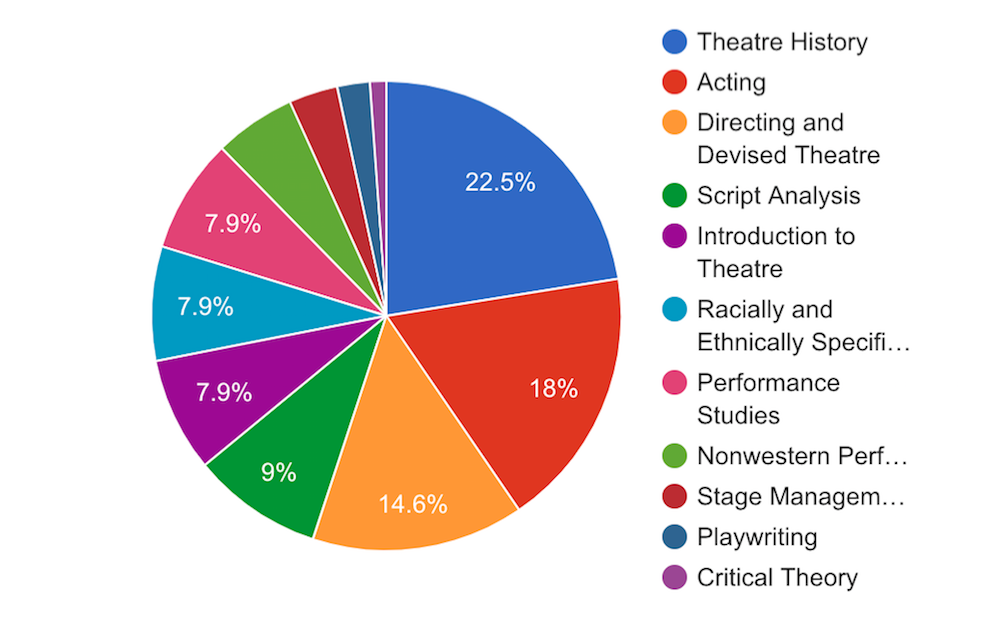

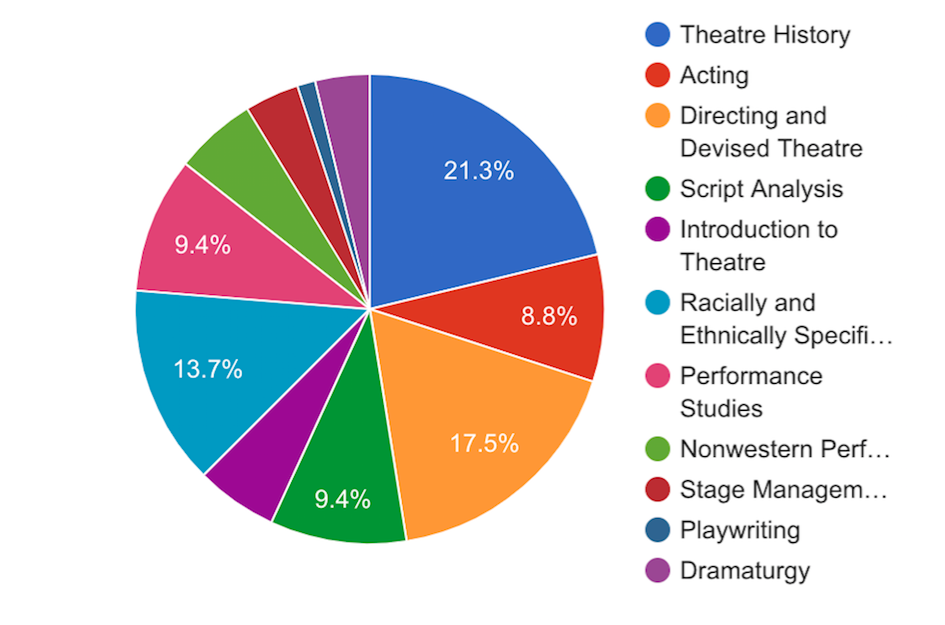

From there, I’d like to talk about the academic job market for Theatre History and Performance Studies PhDs from 2012-2018, drawing from data that my graduate assistants and I have accumulated about hundreds of job ads dating back to the 2012-2013 academic hiring season in order to determine what Theatre and Performance Studies departments are seeking from prospective hires as well as some overviews about the successful applicants hired into colleges and universities from across the country.

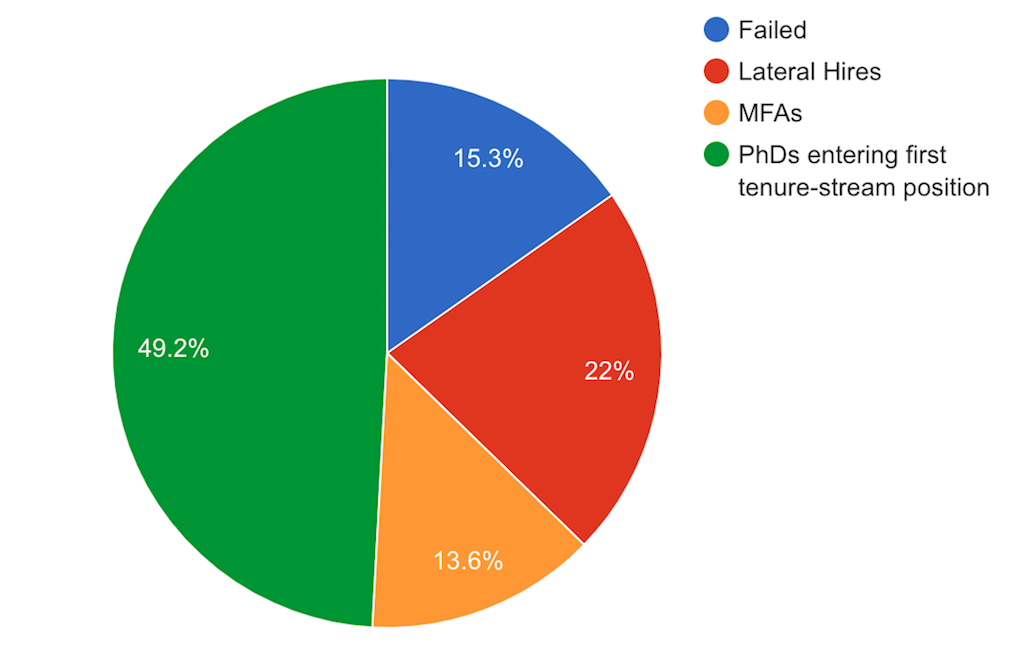

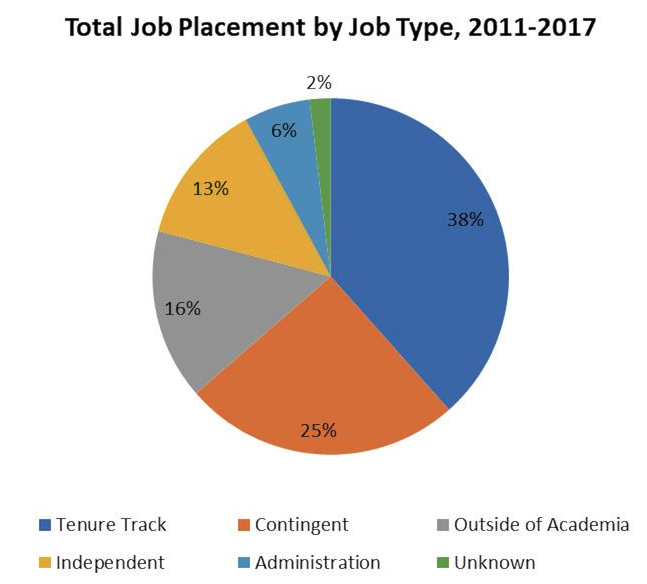

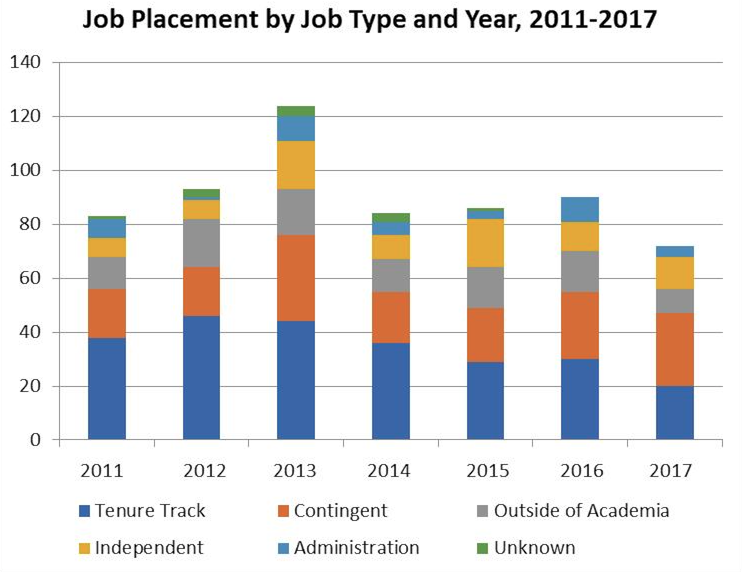

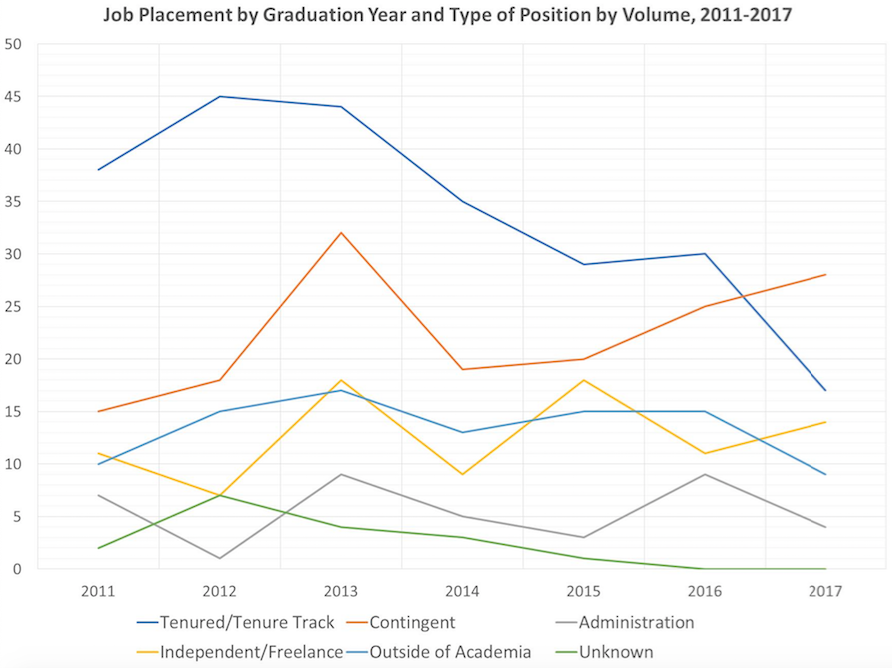

Finally, I’d like to conclude with a snapshot of career paths for the over 600 individuals who have accumulated PhDs in Theatre and Performance Studies from programs in the United States between 2011 and 2017. Using ProQuest’s Dissertation Database and other digitized searches, I’ve learned about the career paths of over 98 percent of the graduates of our collective programs. In doing so, I’ve learned about what programs are successfully placing students in tenure-track and contingent academic positions, and the types of employment opportunities that students are finding when they begin to look for work outside of the academic job markets. I hope that all of this data provides a starting point for thinking about the field, our graduate programs, students who emerge from our institutions with PhDs, and the ways that we can learn to support their work within and beyond academia from coursework to the completion of their degrees.

Part One: Who are our current doctoral students in Theatre and Performance Studies programs and how are they navigating our programs?

Much of the data for this section is drawn from the self-reporting survey that I sent out to every director of a Theatre and Performance Studies PhD program in the United States. Twenty-five of the thirty-six U.S. programs responded to this year’s survey as opposed to the 2015 survey which drew thirty respondents. Although both surveys had over forty questions, I’m only going to focus on a few questions that are particularly germane to this year’s convening.

I’d like to begin by looking at statistics on how many students are currently pursuing doctoral degrees in our programs. In 2015, the mean answer to the question was 17.76 students per PhD program with variations in enrolled students ranging from a one-person PhD cohort to an institution that enrolled sixty-seven doctoral students. This year the mean number of students per PhD program is 18.6 with one university enrolling seven students and another enrolling a high of sixty-two. This increase in program size also corresponds with annual admission patterns.

In 2015, graduate programs that completed the survey admitted a range of one to eight students per year, with a mean enrollment of 3.0. In 2018, responding programs reveal the same minimum and maximum admissions numbers, but the mean number of annually-enrolled graduate students has risen to 3.45 doctoral students per program. As the job market stabilizes following the 2012 recession, the number of students who we’re admitting into our program is slightly growing.

Moreover, as our enrollments increase, the average Theatre and Performance Studies’ PhD student’s time to degree also seems to be seeing a mild uptick in several markers. The survey reveals that graduate students in our programs are taking an average of 2.87 years to finish coursework and other requirements before beginning their dissertations and that the average time to degree is 5.735 years. Both of these data sets mark escalation from 2015 when PhD program directors noted that it took their doctoral students 2.72 years to reach the dissertation stage of their programs and 5.07 years to attain their PhDs. This bears out in the growing number of students who we have in the ABD stage of their programs at present, 10.44 students per doctoral program on average as opposed to 9.24 in 2015.

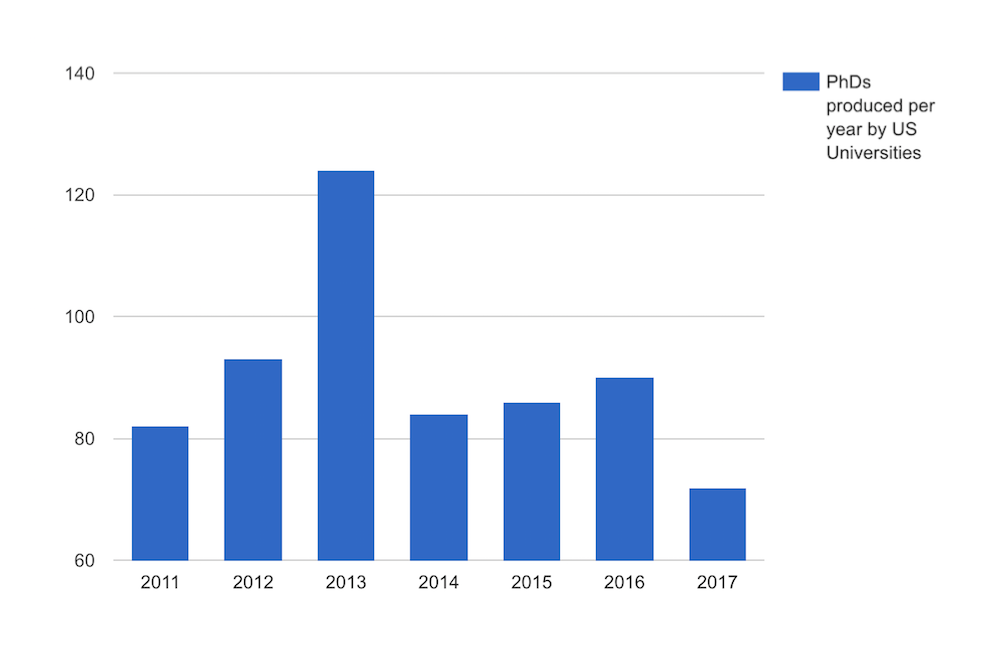

While our admissions numbers and our students’ times to degree are slightly increasing, there is stability in the number of PhDs that we are producing in any year. According to information accumulated from ProQuest’s Dissertation Database and several university libraries, the US-based PhD programs in Theatre and Performance Studies have produced approximately ninety graduates per year between 2011 and 2017. These numbers range from a high of 124 PhDs conferred in 2013 to a low of seventy-two PhDs awarded in 2017. Aside from those two outliers, there is minimal variance in these numbers and we typically find that the field produces somewhere between eighty-five and ninety-five PhDs annually.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here