Symphonie Fantastique and the Triumph and Trap of Puppetry

You can say that Harriet Smithson, a famous Shakespearean actress, is the star of the Symphonie Fantastique by composer Hector Berlioz; she is also in a way the star of the Symphonie Fantastique by MacArthur Foundation “genius” artist Basil Twist—although in the Berlioz, Harriet exists only as flirtatious notes from violins and a flute, while in the Twist, she’s a bed sheet. Or, more precisely, she looks like a white bed sheet, but she’s actually a puppet, one of the many puppets in Twist’s show, none of them conforming to any recognizable animal or vegetable or even mineral. Twist’s puppets are so abstract that, if you ask him how many there are in the show, he’ll say there might be seventy-five, or there might be a thousand.

“It depends on how you count,” Twist told me backstage last week at HERE Arts Center in New York City, after a performance of the twentieth-anniversary production of the piece, which is being presented at the theatre where it debuted in 1998 to great acclaim. Do you count as a puppet every feather or fiber-optic cord even if some of them are attached to one another by wire?

As he was explaining this, the five puppeteers nearby, all dressed in what appeared to be scuba gear (minus the mask), were soaking wet. This might have been a mixture of sweat and water; they had just spent fifty-five minutes manipulating the seventy-five (or one thousand) puppets in a thousand-gallon tank of water, disguised as a puppet theatre.

It takes little more than a glimpse backstage to realize how much Symphonie Fantastique is the story of an obsession—or two obsessions, actually…or maybe three.

When Hector Berlioz was twenty-three years old, the French conservatory student saw the Irish-born actress on a Parisian stage performing as Juliet and Ophelia with a traveling English theatre company. He became instantly infatuated, sending love letters to her hotel. She ignored them, and him. Four years later, in 1830, the twenty-seven-year-old Berlioz composed Symphonie Fantastique, an hour-long romantic symphony in five movements whose subject is the artist’s obsession with Harriet Smithson. The symphony helped Berlioz win her over, and they married. I wish the story ended there, but they eventually divorced. Nevertheless, the symphony made Berlioz a famous composer.

Seventeen decades later, it made Twist a famous puppeteer. He calls himself a third-generation puppeteer, and has always loved puppetry. “All kids connect with puppets,” he has said, “but I was particularly obsessed.” He was twenty-seven years old and near the beginning of his career when he noticed a discarded fish tank on the street, and brought it home to play with. He decided that everything looks better swimming in water. This is how he decided to turn Berlioz’s symphony into a puppet show.

‘[P]uppetry is very much alive and thriving and full of energy’.

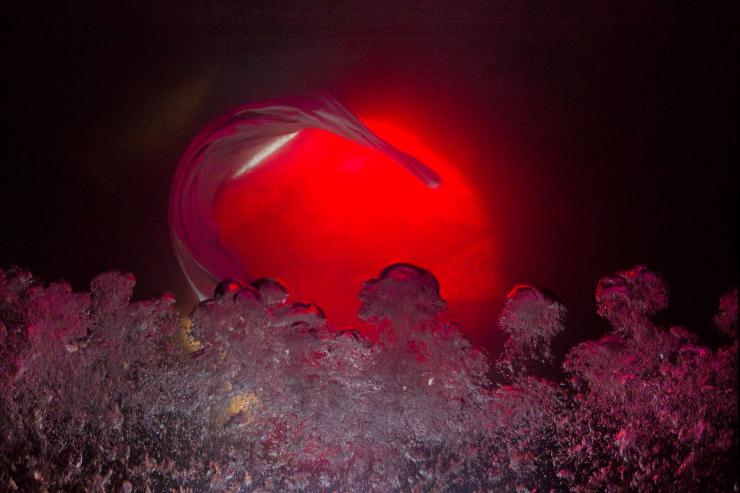

Now, with pianist Christopher O’Riley playing Liszt’s arrangement of Symphonie Fantastique, the accompanying puppetry turns the sound visual. Bubbles ascend in the tank as the music uplifts. Fabrics swirl furiously through inky water as the the pianist barks out a sinister funeral chant. Amoeba-looking plastic cut-outs and pieces of tinsel flow and change tone under Andrew Hill’s lighting design, as the musical notes that seem to drive them change tone as well. It’s dance without dancers. It’s hypnotizing—sometimes, it seems, literally: One of the puppets actually looks like one of those psychedelic pinwheels they used in old ‘60s spy movies to hypnotize the hero.

It brought me back, more than twenty years, to my own obsession.

I first met Basil Twist before he created Symphonie Fantastique, in his cluttered basement studio in a narrow street in the West Village. My first job, when I was eleven years old, had been as an usher for the Bil Baird Marionette Theatre (Baird is best known now for the “The Lonely Goatherd” puppet scene in the film The Sound Of Music), and, though the strings of my amateur Pinocchio marionette had me howling in defeat and despair from a very young age, I’ve been an avid audience for puppetry ever since. So, while covering the 1996 International Festival of Puppet Theatre, I talked to Twist about his entry in the festival, The Araneiadae Show, which he described as “a surreal tale based on a true story that's campy, also tragic and scary and uses a lot of cinematic effects.” He added: “There is some sex in my show.” He demonstrated the R-rated scene: He pulled some levers and two cats copulated. "I think kids would find that funny. But I don't think parents would." (This was some seven years before Avenue Q.)

Outside of the US, puppets are viewed as serious, sexy, intellectual, even sacred; the word marionette (from the French marionnette), means "little Mary," after the Virgin Mary, and puppets still figure in religious ceremonies in Java and Japan, in Bali and Mali, and among Nigerians and certain Native Americans. Virtually every capital in Eastern Europe has a prestigious puppet college, as does France (which is where Basil Twist trained, at the École Supérieure Nationale des Arts de la Marionnette in Charleville-Mezieres.) And many countries in Asia diligently preserve their particular national tradition of a much-venerated puppet art form, which has remained popular in some cases for thousands of years.

"If you look at the history of puppet theatre it was really not something for children," the festival organizer Cheryl Henson told me the same year I first talked to Twist. "Originally, for example, Punch and Judy was political theatre."

Margo Rose, 93 at the time, and a professional puppeteer for more than seven decades, was delighted that “puppetry is very much alive and thriving and full of energy,” with many people trying “new and different ways to use puppets. Some of it is vital and will live, and a lot of it is trash. But the experimenting is very exciting."

But she too thought that most Americans still thought of puppets in too-narrow ways. This came as no surprise to Rose, who had lived trapped in a celebrated pigeonhole for nearly half a century. "We are unfortunately known for Howdy Doody," she told me. From 1947 to 1961, she and her husband, Rufus Rose, made and manipulated all the puppets in the pioneering television show: "It was a very small part of our work."

In the two decades since the debut of Basil Twist’s innovative abstract puppet concert, he has received many accolades and commissions from around the world: operas, ballets, and avant garde theatre. He has created puppets for four Broadway shows, most delightfully The Pee Wee Herman Show. But in many ways, he’s the exception. Two things haven’t really changed. Many Americans still don’t seem to have a broad or deep appreciation for the possibilities of the puppetry arts. And Basil Twist still works out of the same cluttered basement studio in a narrow street in the West Village.

Jonathan Mandell’s NewCrit piece usually appears the first Thursday of each month. See his previous pieces here.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

A perfect description of Basil's studio, and the "trap" many American puppeteers find themselves in. Thank you.

Thanks!

Are you optimistic about the future of puppetry in America?

I am. Even in the relatively short time I have been involved with the medium, I have met some amazing puppeteers -- Basil and his Fantastique crew among them -- and am simultaneously blown away by the "adult" work they are doing and frustrated by the "kid stuff" trope they're working against.

Overall, I do believe strides are being made, albeit far too slowly.