Eating the Rich

Sweeney Todd’s Vicious Capitalism

“There is, in fact, no serious social message in Sweeney [Todd],” the New York Times critic Richard Eder wrote in a review of the show’s original Broadway production in 1979. “At the end, when the cast lines up on the stage and points to us, singing that there are Sweeneys all about; the point is unproven.”

A century or two earlier, philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau said in a speech, “When the people have nothing more to eat, they will eat the rich.”

Since then, the notion of eating the rich has shown up in TV shows, songs, and an assortment of modern memes created largely by a generation that is proving to favor socialism over capitalism. Eating the rich also happens, quite literally, in Sweeney Todd. Rather than merely being a morbid musical tale of personal revenge, it also illustrates through both content and scenic design the damages and desperations that capitalism can inflict on those not already enjoying fortunate lives.

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street is a musical by Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler. It’s about a barber named Benjamin Barker who returns to London under the name of Sweeney Todd, after having been exiled to Australia by the corrupt and powerful Judge Turpin. The judge is cruel and possessive, raping Todd’s wife (now presumed dead) and taking legal ownership of Todd’s young daughter, Johanna, who he later tries to marry.

Todd, with a thirst for blood and vengeance, meets a struggling pie shop owner, Mrs. Lovett. Together, the two enter into a curious business partnership in which Todd shaves men close enough to end their lives and Lovett bakes them into the meat pies she sells to unwitting customers, revitalizing business for the both of them and giving Todd a chance to exact deadly revenge on the judge and his beadle.

“At the top of the hole sit the privileged few / Making mock of the vermin in the lower zoo,” sings Todd in the show’s second song, “There’s No Place Like London.” Capitalism, an economic system where property and businesses are privately owned rather than state-owned, gives people the chance to compete in a free market and make as much profit as cheaply as they can. However, as Oxford professor and author Barbara Harriss-White notes in the Economic and Political Weekly, “Although it creates wealth, by itself capitalist growth is not a solution to poverty. On the contrary, there are many ways in which it causes poverty.” Competitions, after all, have winners and losers.

While certain people tout capitalism as an effective way of living that can provide great personal and financial fulfillment, some say otherwise. Philosopher Karl Polanyi argued in his 1944 book The Great Transformation that the free and self-regulating market is ultimately a utopian hope, and it can lay a foundation for fascism precisely by privileging profit over personhood. “No private suffering, no restriction of sovereignty, was deemed too great a sacrifice for the recovery of monetary integrity,” he wrote.

Intent is not the same as impact, thus Sweeney’s political implications remain and have been emphasized by directors through conceptual choices like scenic design.

In Sweeney Todd, the act of cooking slain humans into pies to sell during a meat shortage is presented not as an unfathomably evil act but as a feasible way to make a living when “times is hard, sir.” Eating the rich is commonly said today to denote a desire to destroy an oppressive upper class and emancipate oneself from capitalism. In Sweeney’s case, when you have a shop to run, demand to keep up with, and money to make, the rich aren’t the only ones being consumed. In a desperate attempt to get revenge and make a decent living (i.e. recover their respective sense of “integrity”), Todd and Lovett end up literally privileging profit over personhood.

It’s not just the book and lyrics of Sweeney Todd that hint at the oppressive nature of class. The original Broadway production, directed by Hal Prince, used scenic design to portray the ensemble as factory workers during London’s Industrial Age, a transformative time that author Henry Heller wrote “marked the climax of the long transition from feudalism to capitalism.” Though the Industrial Revolution caused groundbreaking increases in income, population, and technology in Great Britain, it also created unsafe and poorly paid working conditions for many, as well as long, grueling hours.

“I said to [Sondheim], ‘I can put this in the Industrial Age in a factory, which would make everybody share the same depressing life, and they would be open to revenge’—not all for the same reasons—but they’d be more than slightly unhinged,” Prince told Playbill in a 2017 interview. “The first thing [Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler] said was, ‘Do we have to write for this?’ I said, ‘Absolutely not. I’ll just put it in a factory.’”

In addition to the New York Times critic Eder, another person who proclaimed the musical to have no underlying message was none other than Sondheim himself. But intent is not the same as impact, thus Sweeney’s political implications remain and have been emphasized by directors through conceptual choices like scenic design.

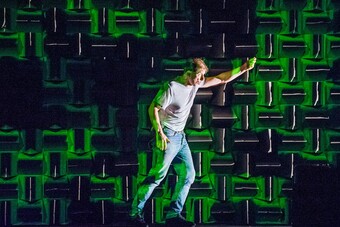

The latest New York production of Sweeney Todd, currently running at the Barrow Street Theatre, was originally presented by London’s Tooting Arts Club. Similar to Prince’s Broadway production, this Sweeney also uses design to reference a piece of working-class English history. Rather than a hulking factory, the story unfolds in an authentic recreation of Harrington’s, a London pie shop that opened in 1908. The original production was literally staged inside that pie shop, and it was so popular that it transferred to the West End.

Barrow Street Theatre’s replica of Harrington’s is small enough that the audience can easily get a view of the whole room, including the prominent menu, which Tooting Arts Club producer Rachel Edwards writes “remains unchanged since the days of Queen Victoria.” Jellied and stewed eels, along with pie, mash, and more, are shown for sale. In actuality, the only pies audience members can purchase are more high-end chicken or vegetarian ones made by a former White House pastry chef, reminding us that most New York theatre caters to those with the money to spend at least $55 per ticket, if not several times that.

Those who say Sweeney doesn’t have a grand moral or political message do have a point. The musical demonstrates the harm capitalism can bring to the lower class, but it doesn’t do much in the way of offering an alternative.

As an American, I was struck by “jellied eels,” which I had never heard of. It turns out that meat pies, mash, and jellied or stewed eels, served with a parsley sauce called liquor, have been a staple of the British poor and working-class for centuries, particularly in East London.

“If you couldn’t afford to eat meat, you could afford to eat eels,” photojournalist Stuart Freedman, who has a book about English pie shops, said in an interview with Saveur. Eels were specifically prevalent because they were cheap, relatively nutritious, and one of the only fishes that could survive the polluted River Thames.

While Prince’s 1979 scenic design concept engaged with the industrial revolution and how its maximizing of work and profit took a “depressing” toll on the worker, Tooting Arts Club’s informs of a longtime institution providing workers with affordable nourishment, even today. It also shows how capitalism’s hand can negatively impact the lower classes. Classic family-owned London pie shops, with their eels and their mash, are still operational today, but estimates reported by the Telegraph reveal only about thirty remain.

The shuttering of shops like this is largely driven by gentrification, another force that goes hand in hand with capitalism. The more trendy restaurants aimed at young residents with disposable income pop up, the more the affordable relics of yore will be pushed out. As always: winners and losers.

Those who say Sweeney doesn’t have a grand moral or political message do have a point. The musical demonstrates the harm capitalism can bring to the lower class, but it doesn’t do much in the way of offering an alternative. The method its characters do choose to cope with the ills of the world—anger, murder, and non-consensual cannibalism—end up creating even more troubles for themselves and others. But those who have been worn down steadily by an oppressive class system do not always have the means to both dream up and execute a productive way of resisting.

“Calls for poor people to empower themselves and support for some of them to organise, while necessary, are not sufficient,” writes Harriss-White in her aforementioned Economic and Political Weekly article. “Such practices are not equal to the ways in which poverty is embedded in the institutions and processes of the capitalist mode of production.”

Eder may not have found a convincing case for there being “Sweeneys all about,” but if you define a Sweeney as someone who has been wronged by people in power and has some irrational fantasies about how to one day get their just deserts, there are plenty. Perhaps it’s wise to instead assume the musical is correct, there are indeed Sweeneys all about, and it’s high time we did something to ensure that our story doesn’t end quite as bloodily for all.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here