Trauma and Agency in Native Son at the Court Theatre

As the lights came up at the close of Native Son, an older African American man sitting behind me murmured to his companion, “Things don’t change.” Nambi E. Kelley’s world premiere adaptation of Richard Wright’s classic novel asks important questions about what has—and has not—changed since the Jim Crow moment in which the play is set. Time is malleable and twisting in Seret Scott’s highly theatrical staging of Native Son at the Court Theatre, a coproduction with American Blues Theater.

Court Theatre is a LORT theater in residence at the University of Chicago; they produce work re-examining classic texts, and since 2010, have been premiering translations and adaptations of classic literature. American Blues Theater is a smaller union theater company dedicated to exploring work that is explicitly “American.” Their collaboration on this project highlights the significance of Wright’s Native Son, a classic work of African American literature.

Kelley uses explosive theatrical language to explore the double-consciousness of Bigger Thomas, and African American man whose life unravels over the course of two cold, snowy days in December 1939 on Chicago’s south side, not far from the current location of the Court Theatre in Hyde Park. Bigger accidentally kills white heiress Mary (Nora Fiffer) and makes a series of increasingly bad decisions in his attempt to initially cover up and then escape the consequences of a mistake. The production opens up a vital conversation about the relationship between the trauma inflicted by a racist society and the agency of its victim, highlighting how he is both the victim of systemic and institutionalized racism and an individual who makes some particularly bad choices.

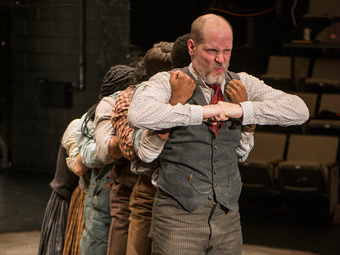

Bigger is represented by two actors. Jerod Haynes plays Bigger as he appears to others and takes action in the real world, while Eric Lynch plays his inner voice, who is given the name “The Black Rat.” The Black Rat initially stands tall and proud in a nicely cut suit while Bigger appears smaller and more vulnerable to his environment. Over the course of show, as Bigger’s situation deteriorates, The Black Rat loses his jacket, begins to appear more disheveled, and by the end of the play appears a broken man, crouching on a step in a corner of the performance space as Bigger runs frantically through the wood-and-steel labyrinth of Regina Garcia’s set—a rat trapped in a cage only partially of his own making.

In this, the production asks white audience members to take a good hard look at how the veil of privilege operates.

Time turns in on itself through the play, as fragments of scenes bleed into each other, events are told out-of-order, and the audience is asked to piece together the events of the evening on which Mary was killed and sift through memories from Bigger’s distant and not-so-distant past. The narrative feels plucked straight from Bigger’s brain in fight-or-flight mode, a stream-of-consciousness series of images and moments informing his actions.

To pretend Bigger is fully an agent of his own fate would be naïve, and it would be just as naïve to present him as an innocent victim. He is human and flawed—full of both rage and dreams. He kills Mary at the end of his first, very uncomfortable evening working as her family’s chauffer. The audience initially only sees Bigger looking miserable helping a very drunk white woman in a silk dress to her room. “Don’t put your head on my shoulder,” he tells her, trying to peel her off of him. Mary just keeps giggling. Her mother calls into her room and Bigger freezes while Mary continues to giggle; when he cannot reason with her to stop, he holds a pillow over her head, admonishing her to be silent and still so he is not caught alone with her.

Later, we are introduced to privileged white liberals Mary and her boyfriend Jan (Jeff Blim)—in 1939, communists, back when “communist” was a viable left-wing political position. They want to break down the walls between whites and blacks. In this, the production asks white audience members to take a good hard look at how the veil of privilege operates—Mary and Jan are quite certain there will be no negative consequences to a night of partying with and getting to know Mary’s new black chauffer. They think they are being both friendly and enlightened including him. However, they have neither the self-awareness to recognize how uncomfortable this clearly makes Bigger nor how actively dangerous it is for him to be with a white woman as she gets very, very drunk. It occurs to no one onstage—Bigger included—that he might be a danger to Mary.

Photo by Michael Brosilow

A refrain repeats throughout the play, “And when you look in the mirror, you only see what you is—a black rat son of a bitch.” Once Mary is dead, Bigger has fulfilled society’s stereotype of a black man as murderer of a white woman. As he attempts to cover up and then escape, he continues to commit a string of increasingly terrible actions ranging from theft to murder. In this transformation, Native Son asks tough questions about the relationship between systemic racism and criminal acts committed by black men. As University of Chicago professor Kenneth Warren points out in the program notes, “You can look at many young men today who made mistakes early in their lives and are made to pay dearly for those mistakes.” Bigger is not innocent—prior to Mary’s death, he had not led an unblemished life—but he would not have committed the murder marking him a wanted man in a society that would not exact dire repercussions on him for being in a white woman’s room. The actions following the murder are his best attempts to escape an impossible situation from which there is, in truth, no hope of escape.

Photo by Michael Brosilow.

At this historic moment in which it is still quite dangerous to be a black man in the United States, Native Son offers an important provocation. For all the world has changed since 1939, the production asks us to take a good hard look at what has not.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here