Under Pressure

Polish Theatre and The Crisis of Public Theatre Institutions

This week on HowlRound, we're looking at different kinds of theatre happening in Poland. In this series, we'll be exploring the historical tradition of the Polish public theatre, the ubiquity of Polish theatre festivals, how theatre in Poland has anticipated and responded to politics, and the current dynamic and vital Polish theatre scene.

Translated by Joanna Kurek, edited by Bartosz Wójcik:

The Polish theatre has always been lively, reacting to current events, at times naming and indicating numerous phenomena more quickly than experts and observers.

History and Theatre in Sync

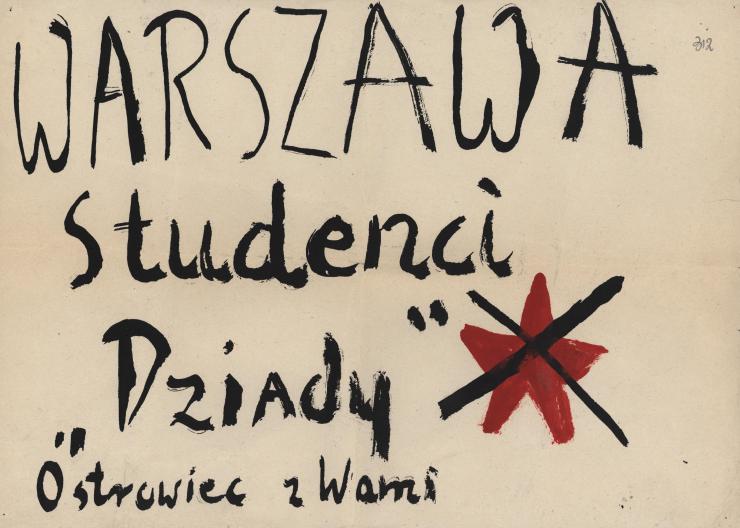

Most of the political breakthroughs in Poland in the past decades were accompanied by significant theatrical events. Alternative and student theatres as well as political theatres have been developed in response to municipal and national theatres, which have often been used as the mouthpieces for regime powers. The 1968 Polish political crisis [Pol: wydarzenia marcowe 1968], one of the deepest political, social, and culture crises in postwar history of Poland, started after the then government banned productions of the iconic play Dziady directed by Kazimierz Dejmek. In addition, the awareness of my generation—those born in Poland in the 1970s and 1980s—was shaped by the consecutive performances of Krzysztof Warlikowski, which ignited the public debate on the topic of the emancipation of Polish homosexuals. The frequent (and often repetitive) watching of Oczyszczeni (2001) [Eng: Cleansed] or Hamlet by Warlikowski (1999), then connected to the Warsaw-based Teatr Rozmaitości, was a vital experience for a whole generation.

A more contemporary example is the performance by Monika Strzępka and Paweł Demirski, entitled: W imię Jakuba S. [Eng: In the name of Jakub S.] created in the Dramatic Theatre in Warsaw in 2011. It ignited a public debate in Poland concerning the class divisions of Polish society and the embarrassing and notoriously overlooked issue of the eighteenth-century colonization and captivity of the peasants dwelling in the areas currently belonging to Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus by the Polish magnates.

At that time, political theatre was no longer using allusion and representation, but rather resorting to new strategies of documentary theatre.

The first decade of the twenty-first century was the time when the new language of the political theatre was born in Poland and the main stage was taken over by younger artists. At that time, political theatre was no longer using allusion and representation, but rather resorting to new strategies of documentary theatre. Examples include: Kiedy przyjdą podpalić dom, to się nie zdziw [Eng.: Do Not Be Surprised When They Come to Set Your House On Fire] by Paweł Demirski (based on the true story of a twenty-one-year-old worker killed by a machine in the Indesit factory in Łódź in 2005, rewritten by Demirski to show how human and workers’ rights are neglected in Polish neoliberal capitalism, even though the system change in Poland in 1989 was possible thanks to the workers’ movement “Solidarność”); Transfer by Jan Klata (premiere 2006) based on accounts of and performed in part by Polish and German witnesses to forced resettlement during World War II; Niech żyje wojna!!! [Eng.: Long Live the War!!!] by Paweł Demirski and Monika Strzępka, one of the most important theatre performances in Poland in the last ten years, in which Demirski and Strzępka reset a well-known Polish TV series about the Second World War, deconstructing the images and myths of war as fun to reveal the childish, sentimental stories, which Polish society seems to be so attached to. Paweł Mościcki, Polish scholar, philosopher, and translator, author of a fundamental book defining a new political theatre in Poland Teatr angażujący [Eng.: Engaging Theatre], refers to the new standards of engaged theatre praxis as an engaging theatre.

An Ongoing Debate

The birth of the new Polish political theatre was accompanied by the “battle for theatre,” the prolonged, heated debate between the conservative critics and those supporting young artists. The public debate, which ran in the Polish media became part of a culture war between the leftists and conservatives aimed to redefine such terms as freedom, society, homeland, politics, as well as to revise the cultural canons and reveal myths and clichés of Polish society. It was mostly in the theatre where this extremely important discourse was created and shaped. This debate constituted yet another formative experience for the then young spectators and theatre enthusiasts, who, put in the middle of a conflict at the beginning of their theatre experience, had to take one or another position. Still, the debate has not yet been resolved.

At the moment, the most audible voice is the voice of those artists, who, tired of accounting for the history of Poland, are sorting out the social mechanisms of remembrance and forgetting (Weronika Szczawińska and Agnieszka Jakimiak, the series Re//mix in the Komuna/Warszawa, curated by Tomasz Plata and Magda Grudzińska), as well as the very means of theatrical expression, which asks about the relationships between the spectator and the artist (Wojtek Ziemilski), borrowing from the visual arts and dance (Komuna/Warszawa, Weronika Szczawińska, Wojtek Ziemilski, Jan Turkowski).

Resetting the Stage

Weronika Szczawińska, nominated in 2014 for a prestigious theatre award by the influential weekly Polityka, is one of the most fascinating and courageous theatre directors in Poland today. Since 2011 she has worked with dramaturg Agnieszka Jakimiak, actor Piotr Wawer Jr., and musician Krzysztof Kaliski. Her main interests are mechanisms of creating individual and common memory (performance: Jak być kochaną?), deconstructing the clichés of Polish history and culture (W pustyni i w puszczy), and reconstructing biographies, identities, and our images about them.

The Re//mix series, initiated in 2010 by theatre scholar and curator Tomasz Plata and theatre Komuna Warszawa, curated by Magda Grudzińska until the end of 2013, was one of the most interesting program proposals in Polish theatre in recent years. During four seasons, young Polish performing artists were invited to create a performance referencing their masters: an icon, an idol—one they were learning from or were rebelling against. Weronika Szczawińska reconstructed the biography of Polish theatre actress and director Lidia Zamkow. Polish choreographer and dancer Mikołaj Mikołajczyk referenced his teacher and master, Henryk Tomaszewski, the choreographer, mime artist, and founder of Wrocław Mime Theatre; Wojtek Ziemilski revealed the methods of the Wooster Group; Aleksandra Borys was inspired by Anna Halprin; and Monika Strzępka and Paweł Demirski referenced the work of Dario Fo.

Wojtek Ziemilski is a theatre director, performer and teacher, whose performances redefine the positions of artist and spectator, giving the audience freedom and tools to create part of the show. His theatre works are highly inspired by conceptual dance and contemporary visual arts, which makes his artistic practice an extraordinary proposal, opening new ways of thinking about what theatre might be.

The most interesting productions in Polish theatre, such as those mentioned above, establish completely new relationships between the scene and the audience.

At present, there are 124 public theatres in Poland, including as many as eighteen in Warsaw.

The Public Theatre and the Demands of the Market

The debate over the state of the institution of the public theatre has also been vigorous in recent years. In Poland, the dominating model is a public, repertory theatre (most frequently a municipal, state-funded theatre), present in almost every big city in the country. Such a public theatre can be defined as a theatrical institution with a fixed group of actors and directors working full time, having a full-time technical team and, on-site set design and costume shops. A public theatre in Poland is financed from public funds (and subordinated to the local and national government). It is most often operating on the basis of a repertory model and led by an artist (usually a director), rarely by a manager, hiring playwrights and literary managers or dramaturgs. At present, there are 124 public theatres in Poland, including as many as eighteen in Warsaw. Their method of funding (the state, the municipality) has significantly contributed to their outstanding artistic achievement. Their size facilitates experimentation (for example, the rehearsals of the plays directed by Krystian Lupa can last several months) and it does not limit the artistic process for commercial reasons. At least this used to be the case.

After the political transformation of 1989, Poland adopted the aggressive, neoliberal model of capitalism, turbokapitalizm, which influenced the management of the institutions of culture inherited from the previous political system (the Polish People’s Republic). Public theatres however, did not engage this reform while the local governments tightened their demands, calling for massive commercial successes, higher revenues and the increase in the number of tickets sold. For this reason, many theatres found themselves in a struggle, committing to obsolete productions, and unwilling to consider collaboration with dance, the visual arts, or international programs that include residencies and partnership opportunities.

The high production costs and the costs of participation in various festivals blocked the path towards experimental artistic quests. In the face of the external pressure concerning revenues and attendance, the theatre is transformed into a factory of consecutive performances with preposterously strict production time frames. In his breakthrough book entitled Resetting the Stage, Dragan Klaić wrote about this particular phenomenon:

Public theatre professionals talk most willingly about the subsidy versus cost gap and various solutions for closing it, but they rarely want to question the institutional model and the patterns of production and distribution that perpetuate the gap. Globalization has imposed the dominance of the financial perspective in debates on contemporary culture— hence the focus on the cost versus revenue issue and at the same time a reluctance of theatre people to acknowledge the fact that public theatre has become a minority option, one among many, in the deployment of people’s leisure time. The harsh competition between public theatre and the cultural industry with its enormous output of digital products has caused some confusion, even bitterness among practitioners.

Nevertheless, Klaić indicates that this applies not only to Poland but also to many countries in Central and Eastern Europe, as well as Germany—the whole region, in which the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were dominated by the model of a repertory theatre:

In Europe, however, a markedly different tradition prevails. …The provisions created after World War II saw theatre as a legitimate beneficiary of the welfare state and an instrument of cultural democratization in Western Europe. Behind the Iron Curtain, in the communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, theatre was pampered as a powerful tool of mass indoctrination.

Today, after the so-called democratic transformation in 1989, which to a huge extent boiled down to the introduction of an aggressive model of capitalism in the post-socialist countries, the public theatre succumbs to the mighty pressure of the economists and politicians fond of the neoliberal definition of an auto-regulating market, and therefore, art institutions are expected to fully provide for their own activities as well as strive to curb or radically minimize public subsidies.

In her essay entitled “Radical Museology,” Claire Bishop, Associate Professor in the History of Art department at the CUNY Graduate Center, emphasizes that bringing the culture under the heavy yoke of economics, severely affects arts institutions, which now have to justify their raison d’être to conform to new metrics, converting the culture-producing role of the theatre into measurable indicators.

We are missing, as Bishop purports, some alternative assessment modules and discussion methods—some specific tools protecting the institution of the theatre from commercialization.

And this is the crucial, perhaps pivotal, paradox of the present day: taking into account the pressures of the market, the cultural institutions postulate the return to the system in which they are financed by the state, which at times can lead to the spread of nationalism and cultural or economic colonization. On the other hand, when the institutions of culture are threatened by nationalistic designs, they defend themselves, resorting to universal values (freedom of speech, artistic cosmopolitism), which in turn have already been commercialized.

Another Week, Another Festival

The situation of the Polish public theatre is also greatly influenced by the phenomenon of “Festivalization.” Currently, there are 677 theatres and 408 professional and amateur festivals taking place in Poland. Thus, there is not a single week without several theatre festivals. On the one hand, the festivals constitute one of the pillars of Polish theatre life: during the festivals the artists can share their experience, exchange business cards, and artists connected to different theatres can watch the work of others and see the impact that their own performances exert over a new audience, within a different context.

On the other hand, the “Festivalization of culture” increases its eventfulness—its transitoriness. Artists are deprived of the possibility of conducting artistic research all year long and instead must prepare, produce, and perform new premieres from one festival to another. But the very same festivals can provide a new, gripping workspace for theatre artists: the consciously curated festivals are trying to abandon their festival identity by offering coproduction and residency opportunities to their artists.

A crisis of our public art institutions offers a chance for change and openness in the long and unpredictable transformation process.

A Real Pressure

Undoubtedly, theatre still has invaluable critical potential. We must not get stuck in mythic notions or erect a monument to the Polish theatre at large—tenderly remembering its enchanting, old history. Instead, we have to provide it with the possibilities for further development. A crisis of our public art institutions offers a chance for change and openness in the long and unpredictable transformation process. This openness is conducive to experiments and trials and can reveal new perspectives and ways of thinking. If we do not make such an effort, artists will not have suitable working conditions and we will be left with a handful of plaintive memories.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here